A map of Native American sign languages isn’t just a linguistic artifact; it’s a profound cartography of cultural resilience, inter-tribal diplomacy, and an ingenious solution to a continent’s vast linguistic diversity. Far from being a mere collection of gestures, these sophisticated systems of communication, often collectively but somewhat inaccurately termed "Plains Indian Sign Language" (PISL) or "Hand Talk," represent a vibrant, living history etched not in ink, but in the eloquent movements of hands and bodies. For the traveler and history enthusiast, understanding this map offers an unparalleled window into the rich tapestry of Indigenous North America, revealing connections and complexities often overlooked by conventional historical narratives.

The Genesis of Hand Talk: A Continent of Voices

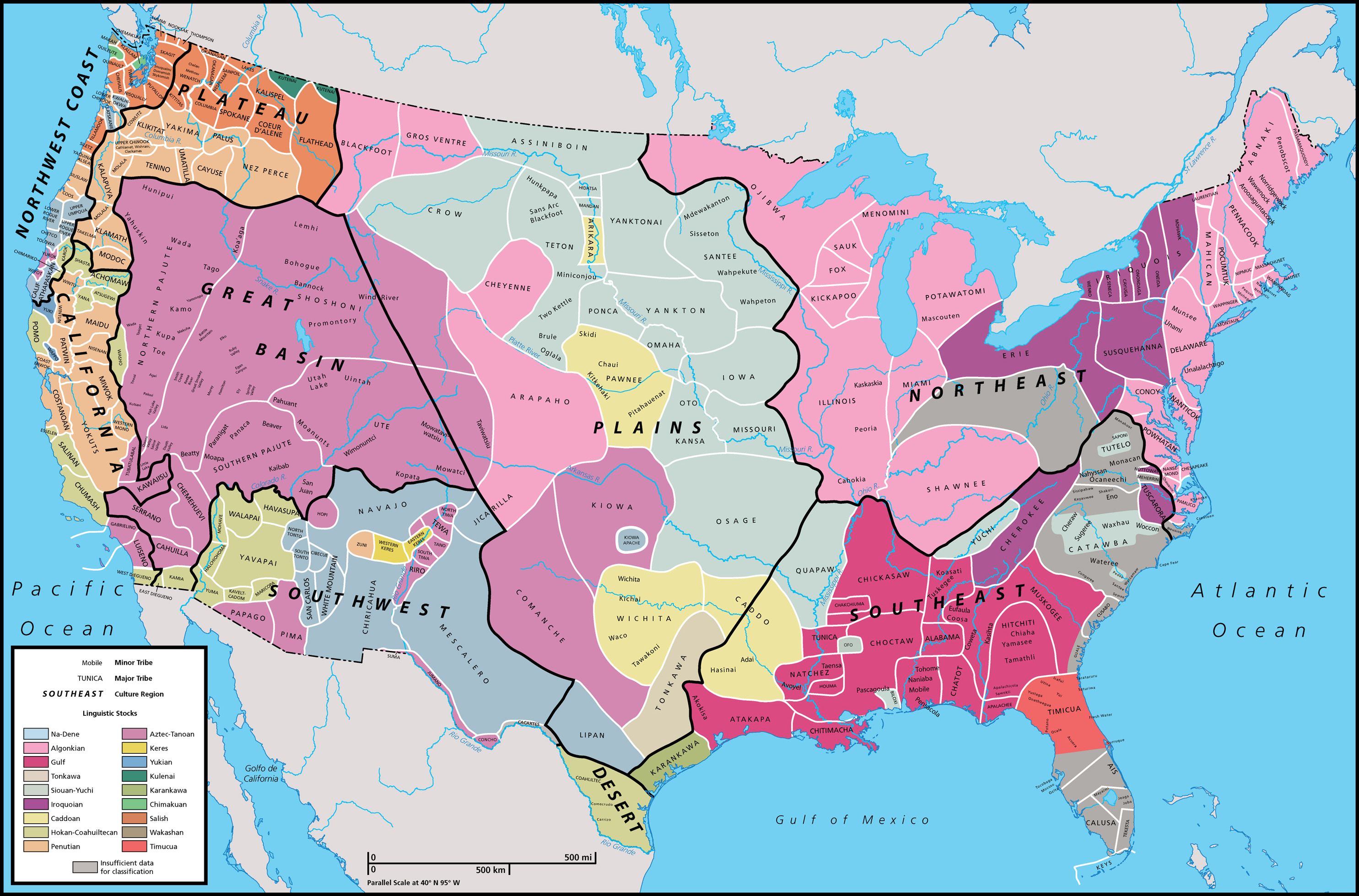

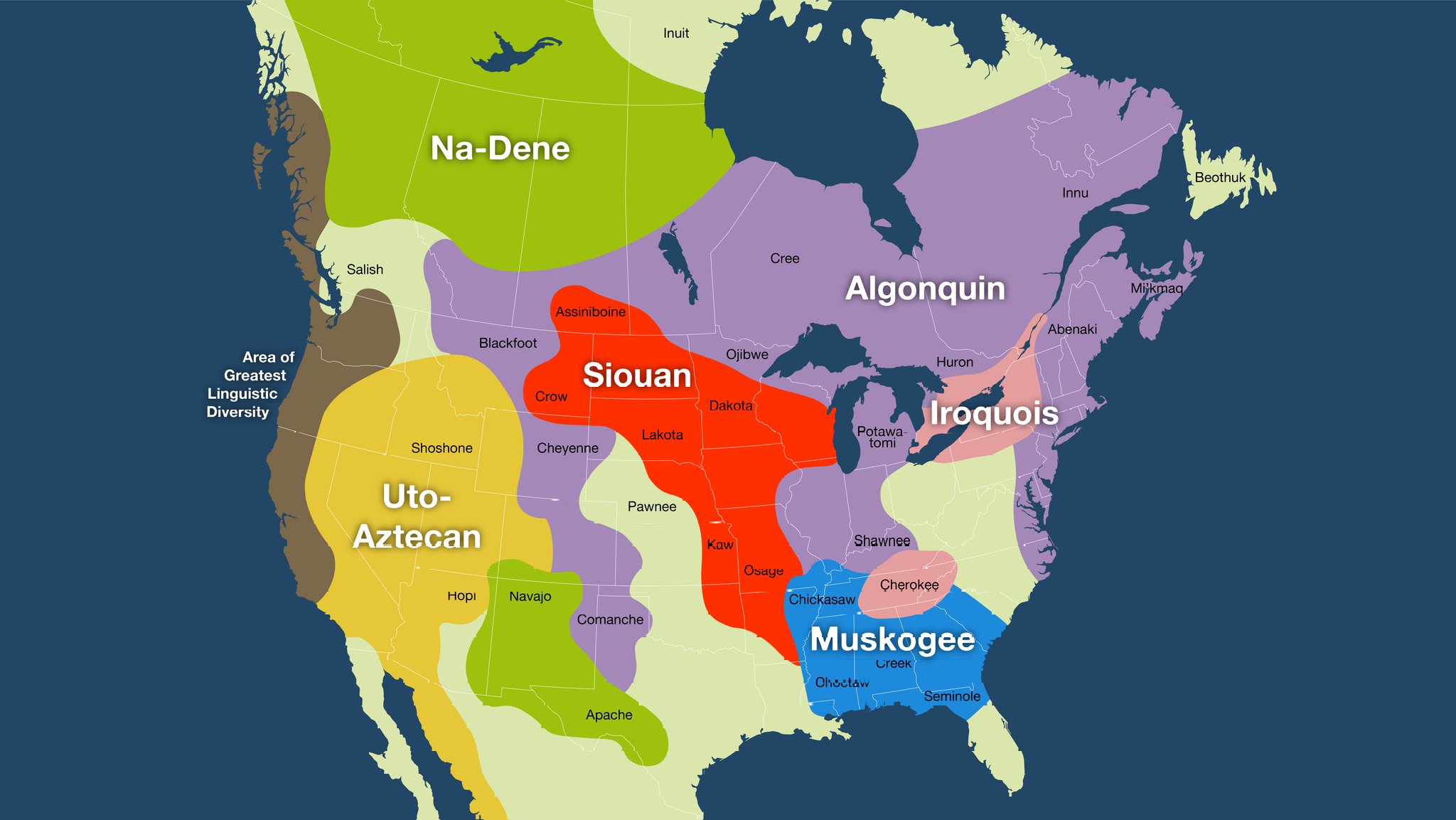

Imagine a continent teeming with hundreds of distinct Indigenous nations, each speaking its own unique language. The linguistic landscape of pre-colonial North America was incredibly diverse, boasting over 300 languages belonging to dozens of unrelated language families – a complexity far greater than that of Europe. While this diversity was a testament to the continent’s rich cultural mosaic, it also presented a formidable challenge for inter-tribal communication. How did nations speaking Siouan, Algonquian, Caddoan, Uto-Aztecan, and Salishan languages engage in trade, negotiate treaties, warn of common enemies, or even share stories around a communal fire?

The answer, etched across the metaphorical map of Native American sign languages, was a brilliant system of mutually intelligible hand gestures. This wasn’t a single, monolithic language, but rather a continuum of related sign systems, sharing a common core vocabulary and grammatical principles, much like spoken language families share roots. While the most widely documented and extensive system developed on the Great Plains, driven by the intense inter-tribal interactions, trade networks, and shared buffalo hunting culture, variations of sign language were used across the continent, from the Pacific Northwest to the Eastern Woodlands.

The "why" behind their development is multifaceted. Firstly, linguistic diversity was the primary driver. Without a common spoken tongue, a visual language became essential. Secondly, trade and diplomacy necessitated a reliable means of communication. Goods, knowledge, and alliances traversed vast distances, requiring effective inter-tribal negotiation. Thirdly, hunting, particularly for large game like buffalo, often demanded silence, making a visual language invaluable for coordinated movements. Finally, and perhaps most profoundly, these sign languages served as a cultural bridge, fostering understanding and empathy between peoples who might otherwise have remained strangers.

Decoding the Map: More Than Just Borders

A map of Native American sign languages wouldn’t show rigid political borders, but rather fluid zones of influence, trade routes, and cultural exchange. It would illustrate a vast interconnectedness, often centered on the Great Plains, where the horse revolutionized mobility and amplified inter-tribal contact. This central hub, often referred to as Plains Indian Sign Language (PISL), served as a lingua franca for a region stretching from the Canadian prairies to Texas, and from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains. Tribes as diverse as the Lakota, Cheyenne, Comanche, Kiowa, Crow, Blackfoot, and Arapaho, despite their distinct spoken languages, could communicate seamlessly through Hand Talk.

But the map’s influence extends beyond the Plains. It would show how these sign systems diffused along trade routes, adapted to local contexts, and sometimes even developed independently in areas with high linguistic diversity or specific environmental needs. For instance, evidence suggests unique sign systems existed among some California tribes, or even within specific contexts like storytelling or religious ceremonies in other regions. The map would, therefore, be less about fixed geographical territories and more about the dynamic flow of human interaction, cultural borrowing, and adaptation. It’s a map of conversations, agreements, and shared experiences.

History in Motion: From Ancient Roots to European Encounter

The origins of Native American sign languages are shrouded in the mists of prehistory, predating European contact by centuries, if not millennia. Archaeological evidence and oral traditions suggest these systems were deeply embedded in Indigenous cultures long before the arrival of outsiders. The sophisticated nature of the languages, with their grammatical structures, nuanced expressions, and ability to convey complex narratives, points to a long period of development and refinement.

The introduction of the horse by Europeans in the 16th and 17th centuries dramatically expanded the reach and necessity of sign language, particularly on the Plains. Horses transformed hunting practices, warfare, and trade, increasing the mobility and interaction between diverse groups. This intensification of inter-tribal contact solidified PISL as the dominant mode of cross-cultural communication in the region.

Early European explorers, traders, and missionaries were often astounded by the efficacy and beauty of Hand Talk. Lewis and Clark, during their epic expedition in the early 19th century, frequently noted their reliance on sign language to communicate with various tribes, often through a chain of interpreters who would translate spoken language into sign, and then sign into another spoken language. George Catlin, the renowned painter of Native American life, documented and marveled at PISL in the 1830s, describing it as a "universal language" of the plains. These early accounts underscore its pivotal role in facilitating understanding across a continent of diverse peoples.

Identity and Sovereignty: More Than Just Utility

The significance of Native American sign languages extends far beyond their practical utility. They are profoundly intertwined with Indigenous identity, cultural expression, and even sovereignty. For many nations, Hand Talk was not just a means to an end; it was an integral part of their cultural fabric.

It was a language of storytelling, allowing elders to transmit oral histories, myths, and legends with visual flair and emphasis. It was a language of ceremony, used in sacred rituals where spoken words might be deemed inappropriate or insufficient. It was a language of artistry, capable of conveying emotions, descriptions, and narratives with an elegance that captivated observers.

Moreover, in the face of colonial expansion and the imposition of European languages, sign language sometimes served as a subtle form of resistance or a private language of sovereignty. It allowed Indigenous peoples to communicate discreetly, share vital information, and maintain cultural cohesion even when their spoken languages were suppressed. It was a testament to their ingenuity and their unwavering commitment to self-determination. The ability to communicate without a common spoken tongue reinforced a sense of shared Indigenous identity that transcended tribal boundaries.

The Shadow of Assimilation and the Light of Revival

The metaphorical map of Native American sign languages also bears the scars of history. The relentless westward expansion of European settlers, the devastating impact of wars, disease, and forced relocation, and especially the insidious policies of forced assimilation profoundly threatened these vital communication systems.

The establishment of government-run and church-run boarding schools, which actively punished children for speaking their native languages (both spoken and signed), was particularly destructive. Generations were robbed of their linguistic heritage, creating a severe break in cultural transmission. As tribal lands were diminished, traditional ways of life eroded, and English became increasingly dominant, the need and opportunity for inter-tribal sign communication waned. By the mid-20th century, many Native American sign languages faced near extinction, used only by a handful of elders.

However, the story does not end in silence. In recent decades, there has been a powerful resurgence of interest and dedication to revitalizing Indigenous languages, including sign languages. Tribal cultural centers, universities, and dedicated individuals are working tirelessly to document, teach, and breathe new life into these precious systems. This revival is fueled by a profound understanding that language is inextricably linked to culture, identity, and sovereignty.

Furthermore, the map of Native American sign languages has found a contemporary connection with Indigenous deaf communities. Historically, deaf individuals within Native American tribes were fully integrated into their communities and often learned and contributed to the existing sign languages, enriching them. Today, the preservation and teaching of these traditional sign systems offer a unique cultural and linguistic bridge for Indigenous deaf individuals, connecting them to their ancestral heritage in a deeply meaningful way.

Traveling Through History: A Call to Understanding

For the modern traveler and student of history, the concept of a map of Native American sign languages offers a profound educational experience. It compels us to look beyond the superficial and engage with the deeper currents of human interaction and cultural innovation. When you visit a historical site on the Great Plains, or walk through a museum showcasing Indigenous artifacts, understanding the role of sign language adds an entirely new layer of appreciation.

Imagine the bustling trade fairs where goods from thousands of miles away were exchanged, all facilitated by the elegant ballet of Hand Talk. Picture the solemn peace councils where treaties were forged, their terms agreed upon through silent, expressive gestures. Envision the shared hunting grounds where tribes, otherwise separated by language, cooperated seamlessly to bring down buffalo.

To appreciate this map is to appreciate the ingenuity, adaptability, and enduring spirit of Native American peoples. It’s an invitation to learn about the complexities of their societies, the depth of their diplomatic traditions, and the richness of their cultural expressions. It encourages us to support language revitalization efforts, visit Indigenous cultural centers, and listen to the stories that continue to be told, whether in spoken word or in the beautiful, ancient language of the hands.

In conclusion, the map of Native American sign languages is not a relic of the past; it is a living testament to human connection, cultural richness, and the power of communication across divides. It serves as a vital educational tool, reminding us that history is not just about conquest and conflict, but also about ingenious solutions, profound identity, and the enduring legacy of diverse peoples who found common ground through the eloquent silence of their hands. It is a journey through a landscape of shared understanding, a journey well worth taking.