Beyond the Spoken Word: Journeying Through the Map of Native American Writing Systems

Forget what you think you know about writing. When we talk about Native American cultures, the image often conjures vibrant oral traditions, intricate storytelling, and the passing down of wisdom through generations of spoken word. While this rich oral heritage is undeniable and central, it often overshadows another profound aspect of indigenous ingenuity: the development and use of sophisticated communication systems that served as precursors, parallels, and even full-fledged writing in various forms.

Imagine a conceptual map, not just of territories and tribes, but of these very systems – a cartography of thought, history, and identity etched across the vast landscape of North America. This map would reveal a mosaic of human innovation, challenging simplistic notions and inviting us to delve deeper into the intellectual achievements of indigenous peoples. For any traveler or history enthusiast, understanding this "map of native writing systems" unlocks a richer, more nuanced appreciation of the continent’s first nations.

The Ancient Foundations: Rock Art, Pictographs, and Petroglyphs

Our journey across this map begins in the deepest past, long before European contact. Across the Americas, from the scorching deserts of the Southwest to the lush forests of the Northeast, thousands of sites bear witness to ancient forms of visual communication: pictographs (paintings on rock) and petroglyphs (carvings into rock).

These aren’t merely "drawings"; they are complex visual narratives, spiritual messages, astronomical observations, territorial markers, and historical records. While not "writing" in the alphabetic sense, they represent a highly developed system of communication, conveying specific meanings to those who understood their conventions. A figure with a specific headdress might denote a particular spiritual being or clan leader; a series of geometric shapes could mark a migration route or a sacred site.

- Identity & History: These ancient markings are invaluable windows into the identity and history of their creators. They tell us about their worldviews, their rituals, their encounters, and their very presence in the landscape. A visit to sites like Utah’s Newspaper Rock, Arizona’s Canyon de Chelly, or the petroglyph fields of the Great Basin offers a tangible connection to these ancient communicators. They are not just art; they are the enduring voices of ancestors, speaking across millennia.

Mnemonic Devices and Proto-Writing: Wampum, Winter Counts, and Khipu

As we move forward in time, our map reveals more structured systems designed for recording information and transmitting complex messages. These are often categorized as mnemonic devices or proto-writing – systems that aid memory and convey meaning without necessarily representing specific sounds of a language.

-

Wampum Belts (Northeastern Woodlands):

- What it is: Wampum consists of beads meticulously crafted from quahog and whelk shells, woven into intricate belts. Far from mere currency, wampum belts were sophisticated records.

- How it functioned: The patterns, colors, and arrangements of the beads encoded treaties, historical events, laws, and ceremonial narratives. When an elder spoke, gesturing to specific parts of a wampum belt, they were "reading" its contents, much like a diplomat might read a written document.

- Identity & History: For nations like the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy), Wampanoag, and Lenape, wampum belts were foundational to their political and social identity. They legitimized agreements, confirmed lineages, and preserved collective memory. To this day, wampum belts are revered cultural artifacts, embodying sacred agreements and the continuity of ancestral law. A visit to a Haudenosaunee cultural center can offer insights into the profound significance of these "talking belts."

-

Winter Counts (Plains Nations):

- What it is: Primarily used by Lakota, Dakota, and other Plains tribes, Winter Counts (or waniyetu wowapi) were pictorial calendars that recorded the most significant event of each year.

- How it functioned: A single image or symbol represented an entire year, creating a chronological history. These were often painted on buffalo hides, muslin, or cloth, arranged in a spiral or linear fashion. The Keeper of the Winter Count would use these images to recall and narrate the full story of each year.

- Identity & History: Winter Counts are incredible historical archives, detailing everything from battles and epidemics to important ceremonies and natural phenomena. They reflect the collective experience and identity of a community, providing a unique indigenous perspective on history. They are living testaments to historical consciousness and the power of visual storytelling.

-

Khipu (Andean Region, Inca Empire):

- A Note on Scope: While not "Native American" in the North American context, the Khipu of the Inca Empire in South America is a powerful example of an indigenous proto-writing system that deserves mention for its sheer complexity. Made of knotted cords, Khipu were used for sophisticated record-keeping, including census data, tribute payments, and potentially even narrative histories. It expands our understanding of the diverse forms indigenous "writing" could take across the Americas.

The Dawn of Syllabaries: Sequoyah and the Cherokee Revolution

Our map takes a dramatic turn in the early 19th century, marking a period of unprecedented indigenous linguistic innovation in North America. This era saw the emergence of true syllabaries – systems where each symbol represents a syllable (like "ba," "be," "bi," "bo," "bu") rather than a single letter or an entire concept. The undisputed star of this chapter is the Cherokee Syllabary, a testament to individual genius and collective determination.

-

Sequoyah’s Innovation (Cherokee Nation):

- The Story: Born around 1770, Sequoyah (ᏍᏏᏉᏯ, also known as George Gist or Guess) was a Cherokee silversmith who, despite being illiterate in English, recognized the power of written communication used by white settlers. He observed their "talking leaves" (books and letters) and understood that the marks represented speech.

- The Process: Over 12 years of tireless work, initially attempting a logographic system (one symbol per word), Sequoyah eventually developed a syllabary of 85 characters. Each character represented a syllable in the Cherokee language.

- Rapid Adoption & Impact: The brilliance of Sequoyah’s system was its logical structure and ease of learning. Within a few years of its completion in 1821, thousands of Cherokee became literate. It was a cultural revolution. The Cherokee Nation quickly adopted it for official purposes, publishing laws, a constitution, and the first Native American newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix (ᏣᎳᎩᏧᎴᎯᏌᏅᎯ).

- Identity & Sovereignty: The syllabary became a cornerstone of Cherokee identity and sovereignty. It allowed the nation to preserve its language, disseminate information, and articulate its rights and grievances during the devastating period of forced removal (the Trail of Tears). It proved that Native Americans were not only capable of adopting new technologies but also of inventing them with unparalleled ingenuity.

-

Other Syllabaries and Adaptations:

- Cree Syllabics: Developed in the 1840s by Methodist missionary James Evans, Cree Syllabics adapted a system of angular symbols, likely inspired by Sequoyah’s success, to represent the sounds of the Cree language. Its simplicity and effectiveness led to its widespread adoption by Cree, Ojibwe, Inuktitut, and other Algonquian-speaking peoples across vast regions of Canada and parts of the United States.

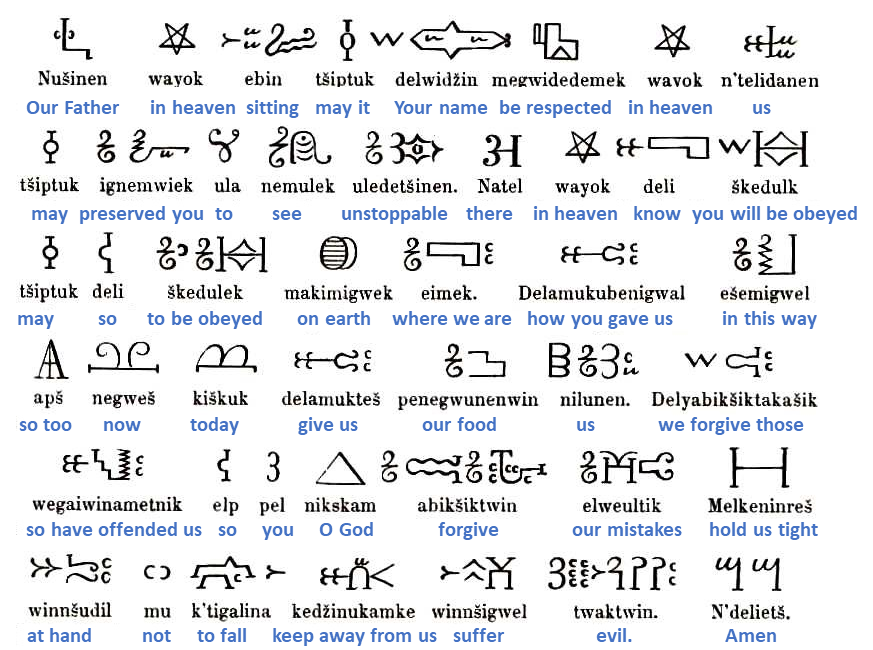

- Mi’kmaq Hieroglyphic Writing: While sometimes attributed to missionary Father Le Loutre in the 18th century, it’s believed that Le Loutre standardized and adapted an existing, older Mi’kmaq system of pictographic or hieroglyphic writing. These symbols were used for prayer books and religious instruction.

- These examples, alongside others like the Ojibwe writing systems, illustrate a period of intense linguistic adaptation and creation, often driven by the need to preserve cultural knowledge in the face of immense external pressure.

The Map’s Deeper Meanings: History, Identity, and Resilience

Understanding this map of Native American writing systems is far more than an academic exercise; it’s a journey into the heart of indigenous history and identity.

- Challenging Misconceptions: It dismantles the pervasive myth that Native American societies were purely oral and lacked sophisticated systems of information storage and retrieval. It highlights their intellectual prowess and capacity for innovation.

- Cultural Preservation: These systems were vital tools for cultural preservation. They ensured that stories, spiritual beliefs, medical knowledge, laws, and historical narratives could endure beyond individual memory, safeguarding them against the erosive forces of time and colonial suppression.

- Identity and Self-Determination: For nations like the Cherokee, literacy in their own language was a powerful affirmation of their distinct identity and a tool for self-governance. It allowed them to resist assimilation and maintain cultural cohesion.

- Resilience and Adaptation: The survival and revitalization of these systems speak to the incredible resilience of indigenous peoples. Despite centuries of colonial policies aimed at eradicating Native languages and cultures – through boarding schools, bans on traditional practices, and forced assimilation – many of these writing systems, or the knowledge of them, persisted.

For the Traveler and the Learner: A Call to Deeper Engagement

Next time you find yourself exploring a national park with ancient rock art, visiting a museum featuring wampum belts, or learning about the history of the Cherokee Nation, let this conceptual map guide your understanding.

- Look Beyond the Surface: See the petroglyphs not just as ancient doodles, but as complex communications. Understand the wampum belt as a living document, not merely a craft item. Appreciate the Cherokee syllabary not as a curiosity, but as a revolutionary act of self-determination.

- Support Revitalization Efforts: Many indigenous communities today are engaged in vital work to revitalize their languages and writing systems. Language immersion programs, digital archives, and community-led initiatives are bringing these ancient and modern forms of communication back to life. Learning about and supporting these efforts is a meaningful way to engage with living indigenous cultures.

- Expand Your Worldview: Recognizing the diversity and ingenuity of Native American writing systems broadens our understanding of what "writing" can be and how humanity has sought to record its experiences. It’s a reminder that wisdom and innovation manifest in countless forms, often outside the dominant narratives.

The map of Native American writing systems is not static; it’s a dynamic testament to human creativity, cultural continuity, and enduring identity. It invites us to listen more closely, look more deeply, and ultimately, to understand the rich and complex tapestry of indigenous history with greater respect and awe. It’s a journey well worth taking, enriching not just our knowledge, but our very perception of history itself.