The map of Native American village structures is far more than a simple geographical representation; it is a meticulously drawn narrative of history, identity, and profound cultural adaptation. Each line, boundary, and depicted dwelling speaks volumes about the people who built them, their relationship with the land, their social hierarchies, spiritual beliefs, and defensive strategies. Understanding these maps means delving into the very essence of indigenous societies across North America, revealing a tapestry of innovation and resilience often overlooked in mainstream historical accounts.

Native American village structures were never arbitrary. They were sophisticated, functional designs, deeply integrated with their environment and worldview. Unlike the often haphazard growth of European towns, many indigenous settlements exhibited clear planning, reflecting a communal ethos, an understanding of natural resources, and a strategic foresight against environmental challenges or external threats.

Regional Diversity: A Mosaic of Structures and Societies

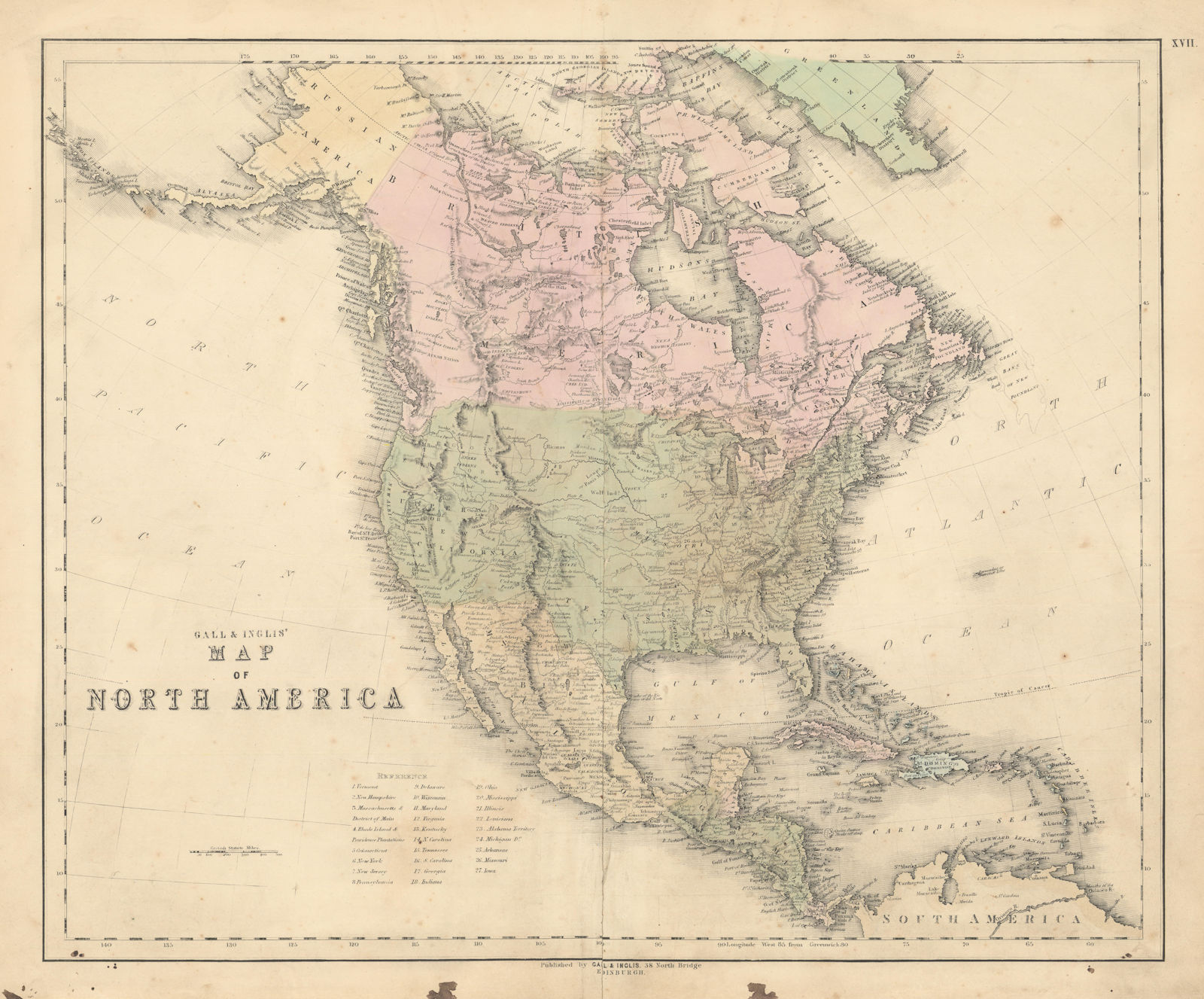

The vast geographical and ecological diversity of North America led to an astonishing array of village structures, each uniquely suited to its region and culture. A comprehensive map would immediately highlight these differences, transforming geographical zones into cultural ones.

In the Northeast, particularly among the Iroquois and Algonquian peoples, village maps would feature longhouses – massive, communal dwellings often exceeding 100 feet in length, housing multiple related families. These structures, built from wood frames covered with bark, were arranged within palisaded walls, indicating a need for defense against rival tribes or, later, European encroachment. The linear arrangement of longhouses often mirrored clan lineages, with a central open space for communal activities. The palisades themselves, sometimes double or triple layered, underscore a history of territoriality and strategic planning for security. A map of an Iroquois village is thus a diagram of social organization, political confederacy, and defensive posture.

Moving south to the Southeast, the map shifts dramatically to reveal the grandeur of the Mississippian cultures and their impressive mound cities. Here, the core of the village was often a vast central plaza, flanked by monumental platform mounds topped with temples, chiefs’ residences, or council houses. Surrounding this sacred and political core would be dense residential areas, sometimes enclosed by defensive stockades. Sites like Cahokia in modern-day Illinois, with its Monk’s Mound rising 100 feet, demonstrate a highly stratified society, sophisticated engineering, and a complex urban planning. A map of a Mississippian city is a testament to centralized power, religious devotion, and the ability to organize vast populations for monumental construction.

The Southwest presents yet another architectural marvel: the Pueblos and cliff dwellings. Maps of these villages reveal multi-story, apartment-like structures made of adobe brick or stone, often built into cliffsides or along river valleys. These communal dwellings, sometimes housing hundreds of people, were designed for defense, climate control (thick walls insulating against extreme temperatures), and community cohesion. Kivas – subterranean ceremonial chambers – are central features, indicating the profound spiritual life integrated into daily existence. The intricate pathways, ladders, and interconnected rooms on a Pueblo map illustrate a society built on communal living, shared resources, and a deep reverence for ancestral lands. The strategic placement of cliff dwellings, like those at Mesa Verde, shows an intimate knowledge of the landscape for both defense and resource management.

On the Great Plains, village structures varied significantly with seasonal mobility. While the iconic tipi represents the highly mobile hunting culture, maps would also show earth lodge villages for semi-permanent settlements, particularly along river valleys. Tribes like the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara built substantial, dome-shaped earth lodges, sometimes 60 feet in diameter, arranged around central plazas. These villages were fortified with ditches and palisades, reflecting their agricultural base and the need to protect harvests from raiding parties. A map of a Plains village thus captures a duality: the temporary, nomadic camps following buffalo herds, and the more permanent, fortified agricultural settlements.

The Northwest Coast featured grand plank houses, often built from massive cedar logs. These long, rectangular structures, sometimes hundreds of feet long, housed extended families and reflected the immense wealth derived from abundant salmon and marine resources. Villages were typically linear, strung along rivers or coastlines, with houses facing the water. The intricate carvings on house fronts and totem poles within the village represented lineage, status, and spiritual beliefs. A map of a Northwest Coast village is a story of wealth, social stratification, and a deep connection to the aquatic environment.

Even in regions like California, where immense linguistic and cultural diversity existed, village maps would show sophisticated adaptations. From redwood plank houses in the north to more ephemeral brush shelters (wickiups) in the south, structures were designed for specific climates and resource availability, often arranged around central ceremonial grounds or shared food processing areas.

Elements of a Map: Unpacking Identity and History

Beyond the type of dwelling, the overall layout of a Native American village map provides critical insights into identity and history.

-

Orientation and Cosmology: Many villages were intentionally oriented towards cardinal directions, celestial events (solstices, equinoxes), or significant landscape features. This was not merely practical; it was deeply spiritual, reflecting their cosmology and understanding of their place in the universe. A village oriented to the sunrise, for instance, speaks of a people who saw themselves in harmony with natural cycles.

-

Central Spaces and Social Cohesion: The presence and design of central plazas, ceremonial grounds, or council areas are crucial. These were the heart of community life, where rituals, dances, games, and political discussions took place. Their size and prominence on a map denote the importance of collective identity and shared experiences. A large, well-defined plaza suggests a strong communal bond and organized public life.

-

Residential Zones and Social Structure: The arrangement of individual dwellings – whether clustered by clan, family, or status – reveals the social fabric of the community. A longhouse village, for example, illustrates a matrilineal society where families live together. A Mississippian city plan, with elites living on mounds and commoners below, signifies social hierarchy.

-

Defensive Features: Palisade walls, watchtowers, strategic placement on defensible terrain (cliffs, islands, peninsulas), and even the lack of such features, tell a story of inter-tribal relations, historical conflicts, and periods of peace. A heavily fortified village indicates a history of conflict and a pragmatic approach to security.

-

Resource Management: The proximity of the village to water sources, agricultural fields, hunting grounds, or fishing weirs, as depicted on a map, highlights sustainable resource management practices. These maps are blueprints of survival, showing how communities thrived in their specific ecological niches.

-

Pathways and Connectivity: Internal pathways within a village dictated daily movement and social interaction. External paths connecting to other villages, trade routes, or sacred sites show networks of communication, commerce, and shared cultural practices.

-

Specialized Structures: The presence of kivas (Southwest), sweat lodges (Plains, Northeast), granaries, or specialized workshops (e.g., flint-knapping areas) on a map indicates the diverse functions and spiritual needs integrated into the village design.

Historical Context: Transformation and Resilience

The historical dimension of these maps is particularly poignant. Pre-contact maps depict vibrant, self-sufficient communities, each a testament to millennia of indigenous innovation. The arrival of Europeans, however, profoundly altered these landscapes. Early colonial maps often reflect European biases, sometimes omitting indigenous settlements or portraying them as chaotic and unplanned.

As colonial expansion progressed, maps of Native American villages began to reflect displacement, disease, and warfare. Villages were abandoned, consolidated under duress, or rebuilt in new locations, often with structures and layouts imposed by colonial authorities. The palisades of the Northeast, once for inter-tribal defense, became critical against European incursions. The vast Mississippian cities, once bustling centers, were often found deserted by early European explorers, victims of disease that preceded direct contact.

Later, maps of reservation lands show a stark contrast: often grid-like, imposed layouts designed for control and assimilation rather than organic community development. These maps represent a painful chapter of forced relocation and the systematic dismantling of traditional social and spatial structures.

Yet, even in the face of immense pressure, the identity embedded in these structures persisted. The memory of traditional village layouts, the orientation to the sacred, and the communal spirit of shared spaces continued through oral histories and cultural practices. Contemporary efforts by Native American communities to reclaim and revitalize their architectural heritage often draw upon these historical maps and oral traditions, seeking to rebuild or design new spaces that reflect their ancestral identity and values.

Mapping Challenges and Interpretation

Interpreting maps of Native American village structures also presents unique challenges. Many early structures were made of ephemeral materials like wood, bark, or animal hides, leaving minimal archaeological traces. Reconstructing these villages often relies on careful archaeological excavation, ethnographic accounts from the contact era, and crucially, the oral histories passed down through generations within Native American communities.

Furthermore, colonial-era maps often suffered from inaccuracies, reflecting a lack of understanding or a deliberate misrepresentation of indigenous settlements. Modern mapping techniques, including remote sensing and GIS, combined with indigenous knowledge, are now providing more accurate and respectful representations, allowing for a deeper appreciation of the complexity and sophistication of these ancient communities.

Conclusion: Living Maps of Identity

A map of Native American village structures is a profound educational tool. It is not merely a depiction of physical spaces but a vibrant historical document, a testament to the ingenuity, adaptability, and spiritual depth of indigenous peoples. Each village layout, whether a fortified longhouse settlement, a sprawling mound city, an intricate Pueblo, or a seasonal tipi camp, tells a unique story of identity – how a people saw themselves, organized their lives, interacted with their environment, and preserved their culture across millennia.

For travelers and history enthusiasts, exploring these maps is an invitation to see North America through a different lens – one that acknowledges the rich, complex, and enduring civilizations that flourished long before European arrival. It encourages a deeper appreciation for the resilience of Native American cultures, whose built environments remain powerful symbols of their enduring presence and their profound connection to the land. These maps are not just historical artifacts; they are living testaments to identities that continue to shape and inspire.