The Enduring Canvas: A Map of Native American Art Forms, History, and Identity

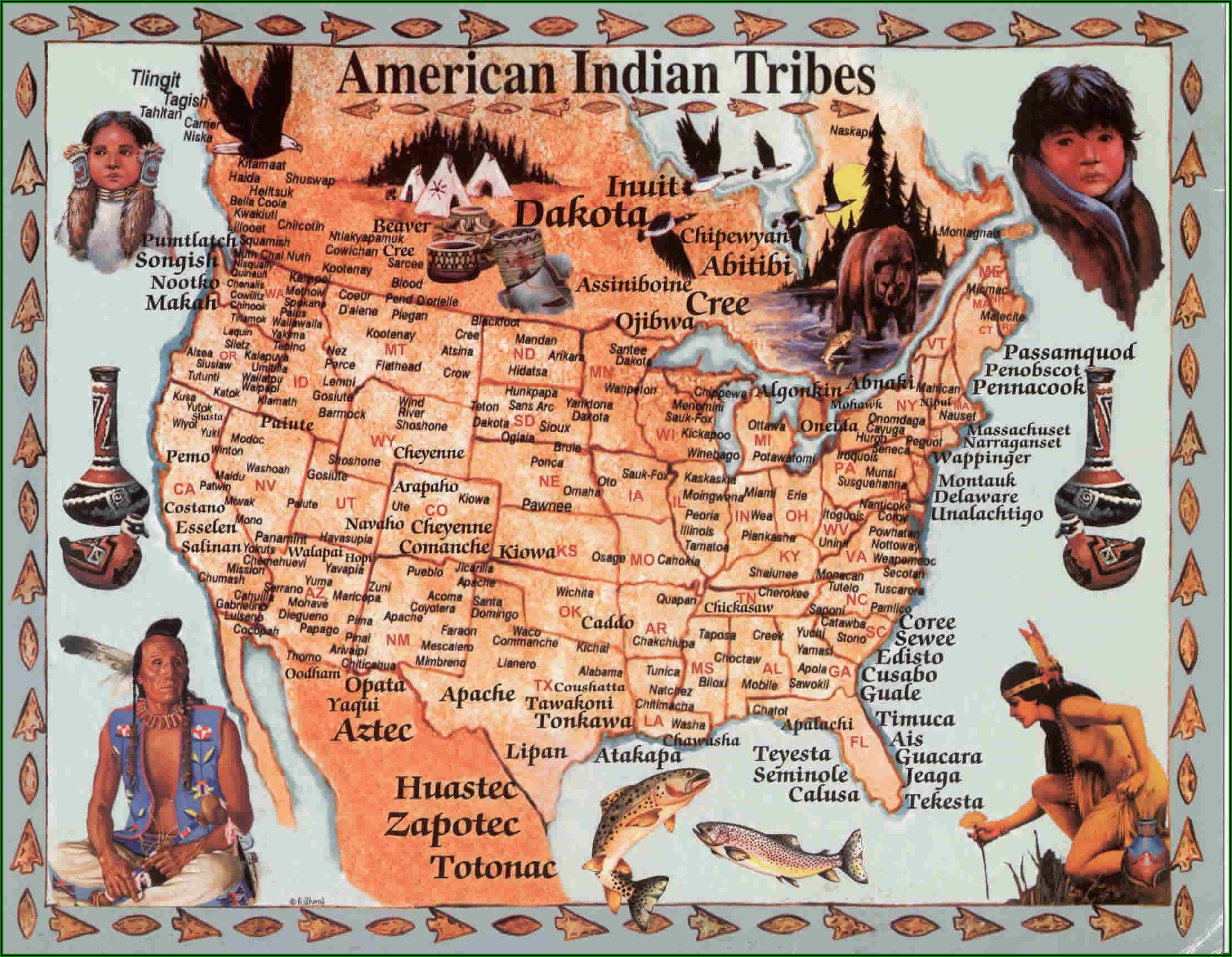

The landscape of North America is not merely a geographical expanse; it is a tapestry woven with millennia of human history, culture, and artistic expression. To speak of a "Map of Native American Art Forms" is not to reference a single cartographic document, but rather a conceptual journey across diverse nations, each imbuing their environment, spirituality, and social structures into breathtaking visual and tangible legacies. This exploration delves into the rich history and profound identity embedded within these art forms, offering a vital perspective for travelers and history enthusiasts seeking a deeper understanding of Indigenous North America.

Forget the simplistic narratives; Native American art is not monolithic. It is a vibrant, evolving spectrum, deeply rooted in specific ecological niches, spiritual beliefs, and community practices. This "map" reveals how distinct cultures, from the frozen Arctic to the arid Southwest, developed unique aesthetic languages that served not only as decoration but as vital instruments for survival, storytelling, and maintaining cosmic balance.

Northeast: Wampum, Quillwork, and Woodland Narratives

The Indigenous peoples of the Northeast, including the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), Wabanaki, and Algonquian nations, developed art forms deeply connected to their forested environments. Perhaps the most iconic is wampum, beads made from quahog and whelk shells. Far from mere currency, wampum belts and strings were intricate mnemonic devices, recording treaties, laws, historical events, and oral traditions. Their patterns and colors carried specific meanings, acting as living documents that solidified alliances and preserved collective memory. A wampum belt, therefore, is not just art; it is a historical archive, a legal contract, and a symbol of sovereignty.

Quillwork, using flattened and dyed porcupine quills sewn onto birchbark or deerskin, was another sophisticated art form. Geometric and curvilinear designs adorned clothing, moccasins, and containers, reflecting a meticulous attention to detail and a profound respect for the natural world that provided the materials. Basketry, often woven from splints of ash or sweetgrass, served both utilitarian and ceremonial purposes, their patterns often echoing the natural rhythms of the forest. These art forms collectively speak of a people living in harmonious, yet complex, societies, where every object held purpose and beauty.

Southeast: Mississippian Mound Builders and Shell Carving

The Southeastern United States, home to nations like the Cherokee, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole, boasts a legacy stretching back to the Mississippian culture (c. 800-1600 CE). This period saw the construction of monumental earthen mounds, often shaped like animals or geometric forms, which served as ceremonial centers, burial sites, and platforms for elite residences. These mounds are themselves massive works of art and engineering, reflecting complex social hierarchies and advanced astronomical knowledge.

Associated with the Mississippian era are exquisite shell gorgets and carvings, often depicting mythological figures, bird-man motifs, or celestial symbols. These intricate pieces, carved from conch shells, were vital components of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, worn as regalia and imbued with deep spiritual meaning related to fertility, warfare, and the cosmos. Later art forms included intricate textiles, pottery with incised designs, and vibrant beadwork that continued to tell stories and adorn individuals with symbols of identity and status. The art of the Southeast is a testament to sophisticated pre-contact civilizations with rich spiritual lives and a profound connection to the earth and sky.

Plains: Nomadic Canvas, Ledger Art, and War Bonnets

The vast grasslands of the Great Plains, home to nations such as the Lakota, Cheyenne, Crow, and Blackfeet, fostered an artistic tradition deeply intertwined with mobility, buffalo hunting, and warfare. Parfleche boxes, made from rawhide, were essential for carrying possessions, adorned with bold geometric designs that were often symbolic and specific to families or individuals. Buffalo hide paintings depicted historical events, battles, and vision quests, serving as visual chronicles for the community.

With the arrival of Europeans and the scarcity of buffalo, a new art form emerged: ledger art. Native artists, often warriors, adapted their traditional narrative painting styles to the pages of ledger books and other available paper, using pencils, crayons, and watercolors to depict daily life, ceremonies, and historical accounts. This art form became a powerful tool for cultural preservation and resistance during periods of immense upheaval.

Perhaps most iconic are the war bonnets, tipi designs, and intricate beadwork and quillwork on clothing, moccasins, and ceremonial items. Each feather, bead, and pattern held specific meaning, denoting valor, spiritual experiences, and tribal identity. The art of the Plains is dynamic, reflecting a life lived in constant motion, yet deeply rooted in spiritual practice and a profound sense of self and community.

Southwest: Earth, Sky, and Enduring Traditions

The arid, dramatic landscapes of the American Southwest, home to the Pueblo peoples (Hopi, Zuni, Acoma, Santa Clara), Navajo (Diné), and Apache, have inspired some of the most enduring and recognizable Native American art forms. Here, art is inextricably linked to agriculture, ceremony, and the natural elements.

Pueblo pottery is renowned for its diverse forms, intricate geometric patterns, and symbolic imagery. Each pueblo has distinct styles, passed down through generations of women potters, reflecting unique spiritual beliefs and artistic lineages. The act of pottery making is often a sacred one, connecting the artist to the earth and ancestral knowledge.

The Navajo (Diné) weaving tradition is equally celebrated, with complex designs and rich colors woven into rugs and blankets. These textiles are not merely decorative; they are narratives, prayers, and reflections of the weavers’ world, often incorporating elements of their spiritual beliefs and the landscapes around them. The famed "Navajo churro" sheep and natural dyes are integral to this tradition.

Turquoise and silver jewelry by Navajo, Zuni, and Hopi artisans is globally recognized. Zuni artists are known for their intricate inlay and channel work, depicting animal fetishes and mosaic patterns. Hopi silverwork often features overlay techniques with symbols from their mythology. Navajo jewelry, often larger and bolder, showcases the beauty of turquoise set in sterling silver. These pieces are not just adornment; they are expressions of identity, wealth, and spiritual connection.

The Hopi Kachina dolls (Katsina in Hopi) are not toys but sacred representations of spiritual beings who visit the Hopi villages. Carved from cottonwood root and meticulously painted, they serve as teaching tools for children and embody the spirits of the Hopi cosmology, bringing blessings and guiding ethical behavior. Sand painting (dry painting) is another profound ceremonial art form, particularly among the Navajo, created for healing rituals and then ritually destroyed, symbolizing the impermanence of beauty and the release of negative energies. The art of the Southwest is a living testament to ancient traditions that continue to thrive and evolve.

Great Basin & California: Basketry as Pinnacle

The Great Basin and California regions, characterized by diverse ecosystems and numerous distinct linguistic groups, saw the development of some of the world’s most exquisite and technically sophisticated basketry. Tribes like the Pomo, Washoe, and Paiute created baskets of incredible fineness, some so tightly woven they could hold water. Materials varied from willow and sedge to tule and fern, often adorned with feathers, shells, and beads.

These baskets served a multitude of purposes: cooking, storage, gathering, winnowing, and ceremonial use. Each stitch, pattern, and form carried cultural significance, often reflecting stories, cosmology, and the identity of the weaver. The skill involved in creating these masterpieces was profound, passed down through generations, making basketry a central artistic and cultural pillar. Rock art (petroglyphs and pictographs) also abounds in these regions, depicting shamans, animals, and abstract symbols, offering glimpses into ancient spiritual beliefs and narratives.

Plateau: Cornhusk Bags and Trade Routes

The Plateau region, situated between the Cascade and Rocky Mountains and home to nations like the Nez Perce, Umatilla, and Yakama, developed art forms that reflected their semi-nomadic lifestyle, rich river systems, and extensive trade networks. Cornhusk bags, intricately woven and often adorned with geometric patterns or figurative designs, were distinctive to the Plateau. They were used for gathering, storage, and as portable canvases for artistic expression.

Like their Plains neighbors, Plateau peoples also excelled in beadwork, applying intricate designs to clothing, bags, and horse regalia. Their art often combined influences from both the Northwest Coast (in some stylistic elements) and the Plains (in materials and techniques), showcasing the dynamic exchange of ideas along ancient trade routes.

Northwest Coast: Totem Poles, Masks, and Formline Art

The lush, resource-rich coastal temperate rainforests of the Pacific Northwest, home to nations such as the Haida, Kwakwaka’wakw, Tlingit, and Salish, gave rise to one of the most distinctive and powerful art traditions in the world. Characterized by a unique aesthetic known as Formline Art, this style uses continuous, flowing lines, ovoid shapes, and U-forms to depict animals, mythological beings, and ancestors in a highly stylized and symbolic manner.

Totem poles are perhaps the most recognizable art form, monumental carvings that serve as crests, memorial poles, or house posts, telling family histories, legends, and significant events. They are visual representations of lineage and identity. Masks, often depicting animal spirits or supernatural beings, are central to elaborate ceremonial dances and potlatches, transforming the wearer and embodying powerful narratives.

Other prominent art forms include intricately carved bentwood boxes for storage, massive canoes for travel and whaling, and exquisite Chilkat and Ravenstail blankets woven from mountain goat wool and cedar bark, depicting complex Formline designs. These art forms are integral to social structure, spiritual beliefs, and the assertion of hereditary rights and status. The art of the Northwest Coast is bold, dynamic, and deeply connected to the marine environment and a rich oral tradition.

Arctic & Subarctic: Carving and Environmental Adaptation

The harsh, yet beautiful, environments of the Arctic and Subarctic, home to the Inuit, Yup’ik, and various Dene nations, fostered art forms that reflected ingenious adaptation and a profound spiritual connection to animals. Carving in bone, ivory, and soapstone is a hallmark of Inuit art, depicting hunters, animals (especially seals, polar bears, and whales), and mythological figures. These carvings are not only aesthetically pleasing but often served as amulets, teaching tools, or narrative devices.

Parkas and other clothing items, skillfully constructed from animal hides and furs, were not merely functional; they were often adorned with intricate patterns, embroidery, and decorative elements that conveyed identity and spiritual protection. The art of these regions speaks of resilience, resourcefulness, and a deep understanding of the animal world, where the boundaries between human and animal, physical and spiritual, are fluid.

Shared Threads: Art as Identity, History, and Resilience

Despite their immense diversity, these regional art forms share fundamental characteristics. Across the continent, Native American art is rarely "art for art’s sake." It is deeply functional, serving utilitarian, ceremonial, or narrative purposes. It is inextricably linked to spirituality, acting as a conduit to the sacred, embodying prayers, and manifesting spiritual power. It is a powerful form of storytelling, preserving histories, myths, and ancestral knowledge in visual language.

Crucially, Native American art is a profound expression of identity. It affirms individual, family, clan, and tribal belonging. It embodies a people’s relationship with their land, their ancestors, and their place in the cosmos. For generations, especially after European contact, when Indigenous languages were suppressed and cultures attacked, art became a vital means of cultural survival and resistance.

The historical trajectory of Native American art is one of remarkable resilience. The devastating impacts of colonization – disease, forced relocation, assimilation policies, and the destruction of traditional lifeways – severely disrupted many art forms. Materials became scarce, skills were lost, and the cultural contexts for creation were undermined. Yet, Indigenous artists adapted, innovated, and persevered.

Today, Native American art is experiencing a vibrant resurgence. Contemporary artists are drawing upon ancestral traditions while infusing them with modern perspectives, materials, and techniques. This revival is not merely an aesthetic movement; it is a powerful assertion of sovereignty, cultural continuity, and self-determination. Through their art, Native peoples continue to tell their stories, challenge stereotypes, educate the world, and celebrate their enduring heritage.

For the Traveler and Educator: Engaging Respectfully

For those drawn to the rich tapestry of Native American art, this conceptual "map" serves as an invitation to engage with deep respect and an open mind.

- Support Native Artists: Whenever possible, purchase art directly from Native artists or through reputable Native-owned galleries and cultural centers. This ensures fair compensation and directly supports Indigenous communities.

- Visit Cultural Institutions: Explore tribal museums, cultural centers, and well-curated exhibitions that prioritize Indigenous voices and perspectives.

- Learn the Context: Understand that each art form is embedded in a specific history, language, and worldview. Avoid generalizing or romanticizing.

- Challenge Stereotypes: Recognize that Native American cultures are diverse, dynamic, and contemporary. Move beyond outdated images and appreciate the living, evolving nature of Indigenous art and identity.

The "Map of Native American Art Forms" is not static; it is a living, breathing testament to the ingenuity, spirituality, and indomitable spirit of Indigenous peoples across North America. It invites us to look beyond the surface, to understand the profound history and identity woven into every thread, carved into every pole, and painted onto every surface. It is a journey into the heart of a continent, revealing that art is not just what we see, but how we understand who we are, where we come from, and where we are going.