Charting Resilience: A Map of Native American Land Trusts

The story of Native American land is a profound narrative of loss, resilience, and reclamation. For millennia, Indigenous nations stewarded a continent, their identities inextricably woven into the fabric of the land. European colonization, driven by doctrines of discovery and manifest destiny, systematically dispossessed these peoples, culminating in a fragmented landscape of reservations and diminished sovereignty. Yet, amidst this historical trauma, a powerful movement for land reclamation and stewardship has emerged: Native American land trusts. A map illustrating these land trusts is not merely a geographic representation; it is a dynamic testament to enduring identity, cultural revitalization, and the ongoing struggle for self-determination. For travelers and history enthusiasts alike, understanding this map offers a vital lens into the heart of contemporary Native America.

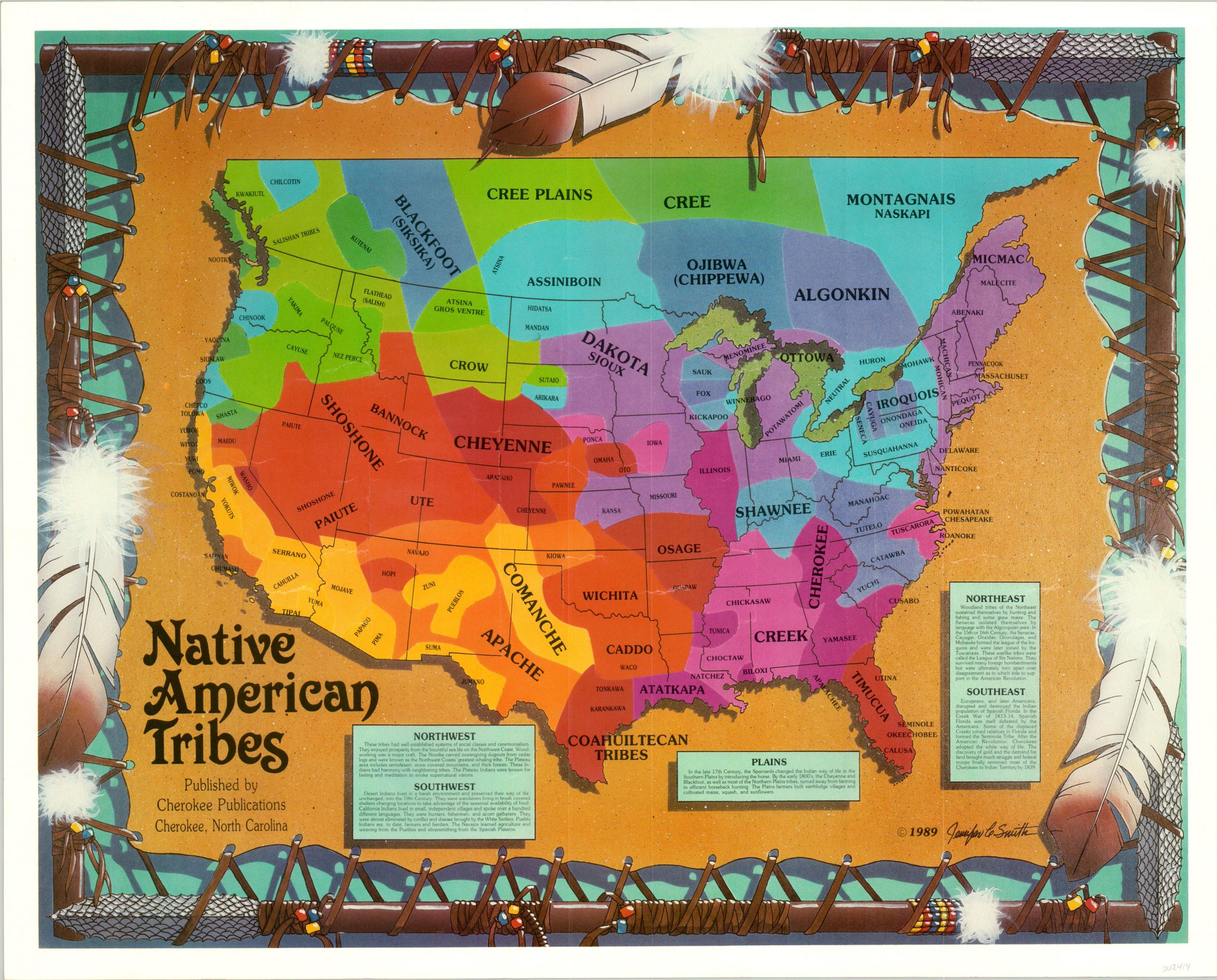

To grasp the significance of Native American land trusts, one must first confront the historical cataclysm that necessitated their creation. Prior to European contact, Indigenous nations occupied and managed the entirety of North America, their diverse cultures, languages, and spiritual practices deeply rooted in specific territories. Land was not a commodity to be bought and sold, but a living entity, a relative, sustaining life and identity. The arrival of European powers initiated a devastating erosion of this relationship. Early treaties, often coerced and frequently violated, whittled away ancestral domains. The 19th century brought an onslaught of genocidal policies, most notoriously the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which forcibly displaced countless nations from their homelands in the southeastern United States to "Indian Territory" (present-day Oklahoma).

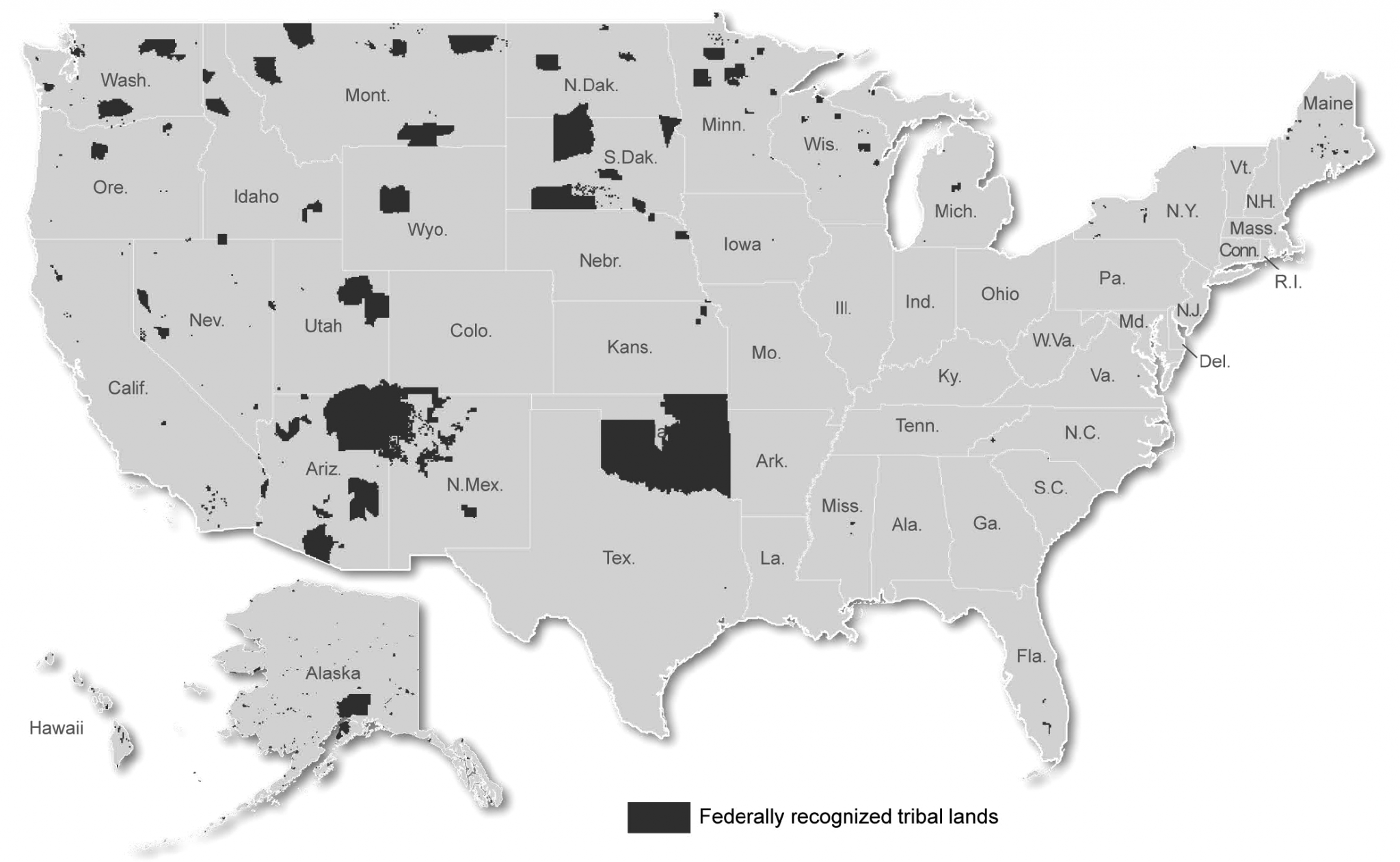

Even the creation of reservations, initially intended to secure a portion of tribal lands, proved to be a temporary reprieve. The Dawes Act (General Allotment Act) of 1887 fragmented communal tribal lands, allotting individual parcels to Native families with the remaining "surplus" land opened to non-Native settlers. This policy aimed to assimilate Native peoples by destroying their communal land base and traditional governance structures. By the mid-20th century, Native landholdings had plummeted from over 138 million acres in 1887 to just 48 million acres by 1934, much of it held in trust by the federal government and subject to its often paternalistic control. This history of dispossession, broken promises, and cultural assault underscores the profound importance of every acre reacquired or protected by Native communities today.

In this context, Native American land trusts represent a vital and proactive response to centuries of land loss. Generally, a land trust is a non-profit organization that actively works to conserve land by acquiring it or by working with landowners to place permanent conservation easements on their property. Native American land trusts, however, carry a far deeper mandate. They are typically Indigenous-led organizations, often affiliated with specific tribes or intertribal groups, dedicated not only to ecological preservation but also to the reacquisition, protection, and stewardship of ancestral lands for cultural, spiritual, and economic purposes. Unlike federal reservations, which are held in trust by the U.S. government, lands acquired by Native land trusts are often held directly by the tribal entity or the non-profit, providing a greater degree of self-determination and control. These trusts acquire land through various means: donations, purchases, and sometimes through direct transfers from other conservation organizations or governmental bodies.

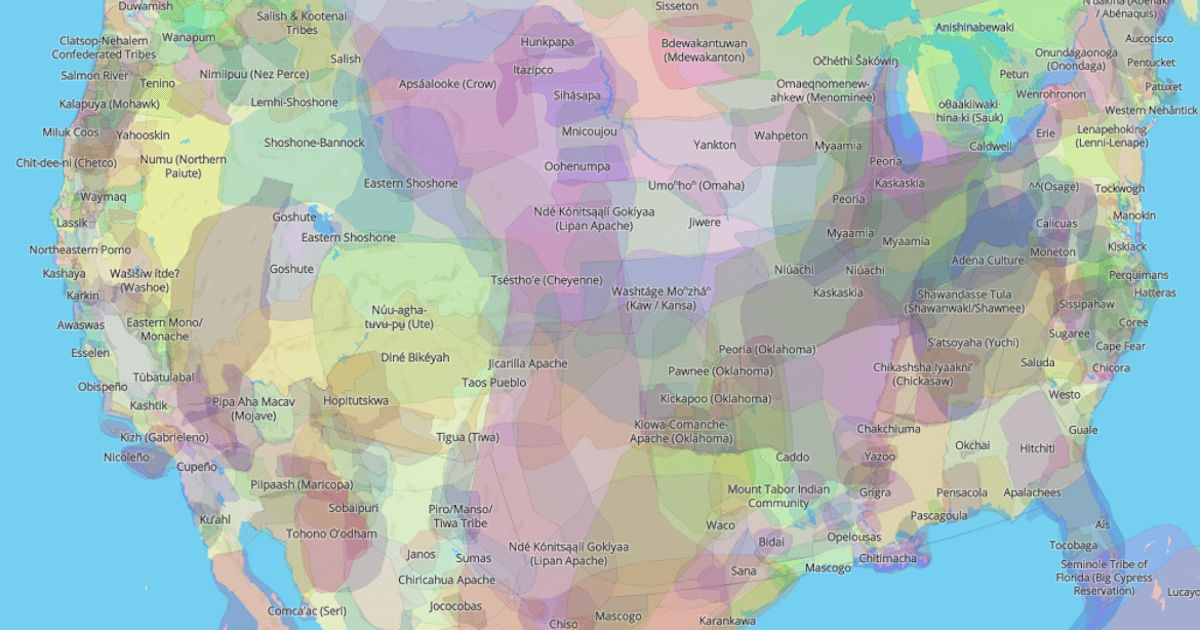

A map depicting Native American land trusts would therefore not be a static image, but a living document of resurgence. Each shaded area or pinpoint on such a map signifies a victory, large or small, in the ongoing effort to heal historical wounds and build a sustainable future. These locations are diverse: some are small, culturally significant parcels within or adjacent to existing reservations; others are vast tracts of ancestral land reacquired in areas where tribes no longer had a federal land base. The map would highlight areas critical for the protection of sacred sites, burial grounds, traditional food sources, and crucial ecological habitats. It would show lands being managed for bison restoration, traditional farming, language immersion programs, and the practice of ceremonies that were once suppressed. Each point on this map is a narrative, often a complex saga of negotiation, fundraising, legal battles, and community organizing, all fueled by an unwavering commitment to identity and heritage.

For Native peoples, land is not merely property; it is the foundation of identity, spirituality, and cultural survival. The concept of "land back" extends beyond simple ownership to encompass the restoration of traditional land management practices, food systems, and governance. Native American land trusts are instrumental in facilitating this comprehensive vision. They allow communities to revitalize Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), which offers profound insights into sustainable land management honed over millennia. This includes practices like prescribed burning to prevent wildfires, selective harvesting, and the cultivation of native plants. The reacquisition of land also provides secure spaces for cultural ceremonies, language immersion camps, and intergenerational teaching, ensuring that vital traditions are passed down to future generations. Moreover, these trusts often focus on food sovereignty, restoring access to traditional foods like wild rice, salmon, and buffalo, which are central to Native diets and health, both physical and spiritual. This self-determination over land allows tribes to pursue economic development on their own terms, creating opportunities that align with their values and benefit their communities directly.

Despite their vital role, Native American land trusts face significant challenges. Funding remains a constant hurdle, as acquiring and managing land is an expensive endeavor. Legal complexities, including navigating state and federal regulations, can be daunting. There are also ongoing political battles, often rooted in historical prejudices, where local communities or state governments resist tribal land acquisitions or the exercise of tribal sovereignty. Furthermore, these lands are not immune to the impacts of climate change, from increased wildfires to water scarcity, which demand adaptive and resilient stewardship strategies. Yet, the movement continues to grow, fostering partnerships with non-Native conservation organizations, engaging in public education, and inspiring a broader "land back" discourse that challenges conventional notions of land ownership and conservation.

A map of Native American land trusts is far more than a cartographic exercise; it is a powerful visual representation of hope, resilience, and the enduring spirit of Indigenous peoples. For the traveler and history enthusiast, it serves as an invitation to look beyond conventional tourist routes and engage with a deeper, more profound narrative of this continent. It encourages respectful visitation where appropriate, support for Indigenous-led initiatives, and a commitment to learning from the wisdom of Native land stewards. This map is a living testament to the fact that despite centuries of attempts to erase them, Native American nations are not only surviving but thriving, reclaiming their heritage, healing their lands, and charting a powerful course for a future where their identity, culture, and sovereignty are unequivocally celebrated and protected.