Tracing the Scarred Landscape: A Map of Native American Forced Removals

The landscape of North America is not merely a collection of physical features; it is a palimpsest, bearing layers of human history, culture, and profound trauma. For those seeking to understand the continent’s true narrative, a crucial lens is the "Map of Native American Forced Removals." This isn’t just a static cartographic representation; it’s a dynamic, agonizing chronicle of dispossession, resilience, and the enduring spirit of Indigenous peoples. For the history-conscious traveler and the curious mind, this map offers an indispensable journey into the heart of America’s past, revealing truths often obscured but vital for a complete understanding of identity and place.

The Fabric of a Continent: Before the Removals

Before the advent of European colonization, North America was a vibrant tapestry woven by hundreds of distinct Native American nations, each with unique languages, spiritual beliefs, governance systems, and intricate relationships with their ancestral lands. From the agricultural societies of the Southeast like the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole, to the nomadic hunters of the Great Plains, the sophisticated pueblo dwellers of the Southwest, and the intricate fishing cultures of the Pacific Northwest, Indigenous peoples had cultivated diverse and sustainable ways of life for millennia. Their presence was not merely a territorial claim but an inseparable bond of identity, spirituality, and subsistence forged over countless generations. The land was not just property; it was kin, a living entity that defined who they were.

The arrival of Europeans shattered this equilibrium. Initial encounters often involved trade and uneasy alliances, but the relentless pressure of colonial expansion, driven by insatiable demands for land and resources, quickly escalated into conflict and disease. As the nascent Uniteds States grew, its westward expansion became an ideology of "Manifest Destiny," implicitly asserting a divine right to conquer and occupy the entire continent. This expansion, however, was fundamentally predicated on the displacement and subjugation of the Indigenous populations who already called these lands home.

The Genesis of a Policy: From Coexistence to Coercion

Early U.S. policy toward Native Americans was a complex and often contradictory mix of assimilationist ideals and outright land hunger. Figures like Thomas Jefferson, while espousing a vision of Native Americans adopting American agricultural practices and eventually integrating into society, also openly contemplated their removal beyond the Mississippi River to accommodate white settlement. This idea, initially presented as a benevolent solution, quickly morphed into a coercive tool.

The turning point arrived definitively in the early 19th century, particularly during the presidency of Andrew Jackson. Jackson, a veteran of several campaigns against Native American tribes and a staunch advocate for white expansion, epitomized the era’s prevailing sentiment. His administration, fueled by the Georgia gold rush and the desire for cotton-growing land in the Southeast, championed the policy of "Indian Removal." This was not merely about moving people; it was about systematically dismantling sovereign nations to seize their ancestral territories.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 and its Aftermath

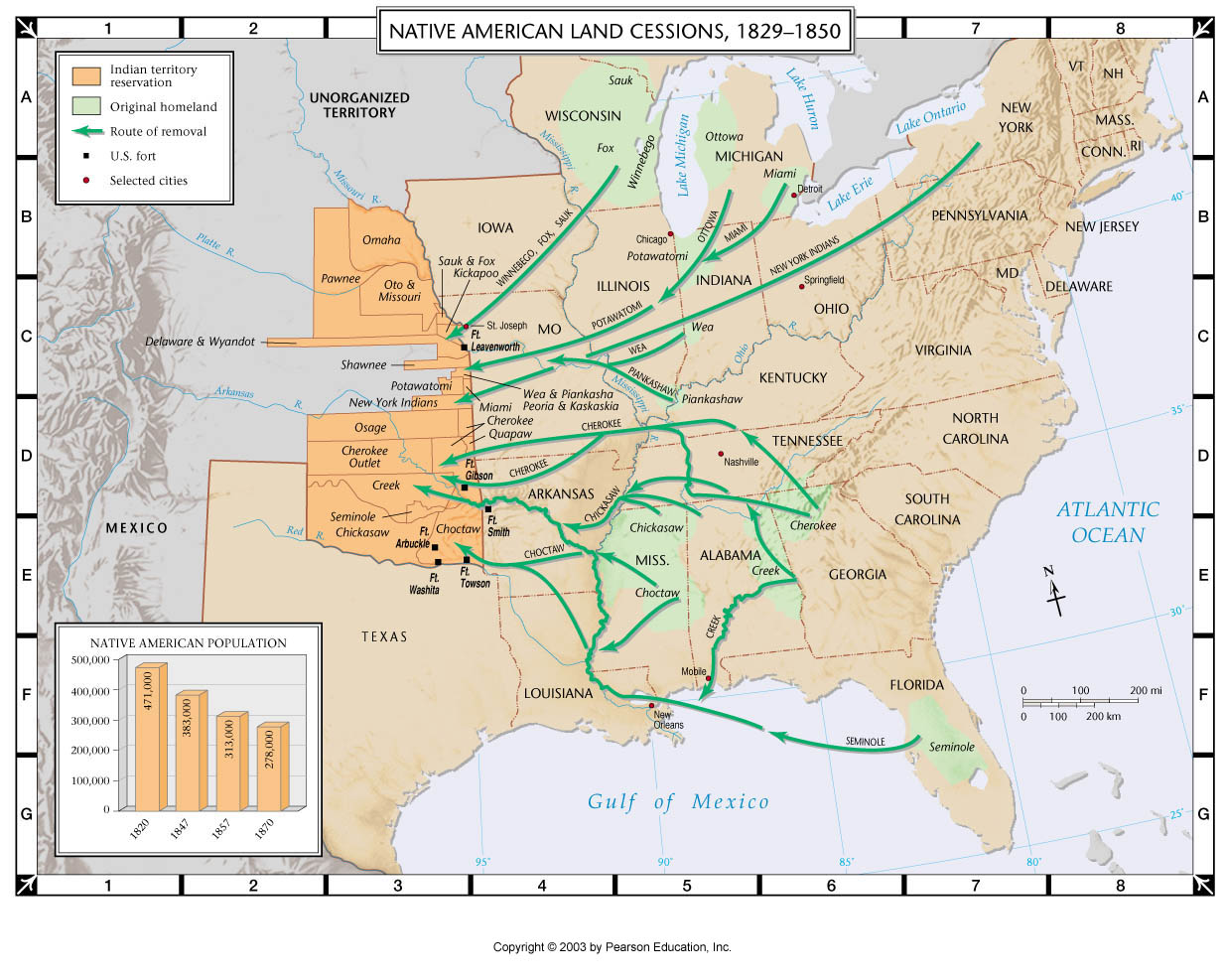

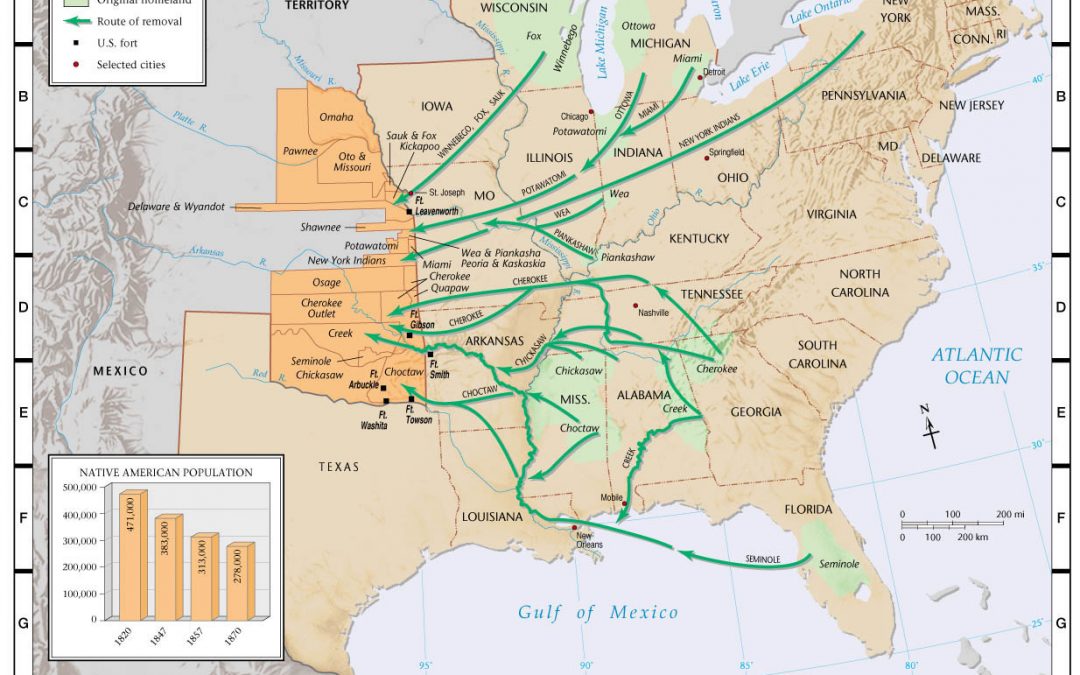

The legislative cornerstone of this brutal policy was the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Passed by a narrow margin in Congress, the Act authorized the President to negotiate treaties for the removal of Native American tribes from their lands east of the Mississippi River to lands west, primarily in what was designated "Indian Territory" (present-day Oklahoma). While framed as "voluntary" negotiation, the reality was stark: tribes faced immense pressure, military threats, and often fraudulent treaties signed by unrepresentative factions.

The Supreme Court, under Chief Justice John Marshall, initially offered a glimmer of hope for Native sovereignty. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), the court recognized the Cherokee as a "domestic dependent nation." A year later, in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the court explicitly ruled that Georgia state law had no jurisdiction over Cherokee lands, thereby affirming tribal sovereignty and invalidating the state’s efforts to seize their territory. However, President Jackson famously defied the ruling, allegedly stating, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it." This political will, overriding judicial authority, sealed the fate of many tribes.

The Trails of Tears: A Map of Suffering

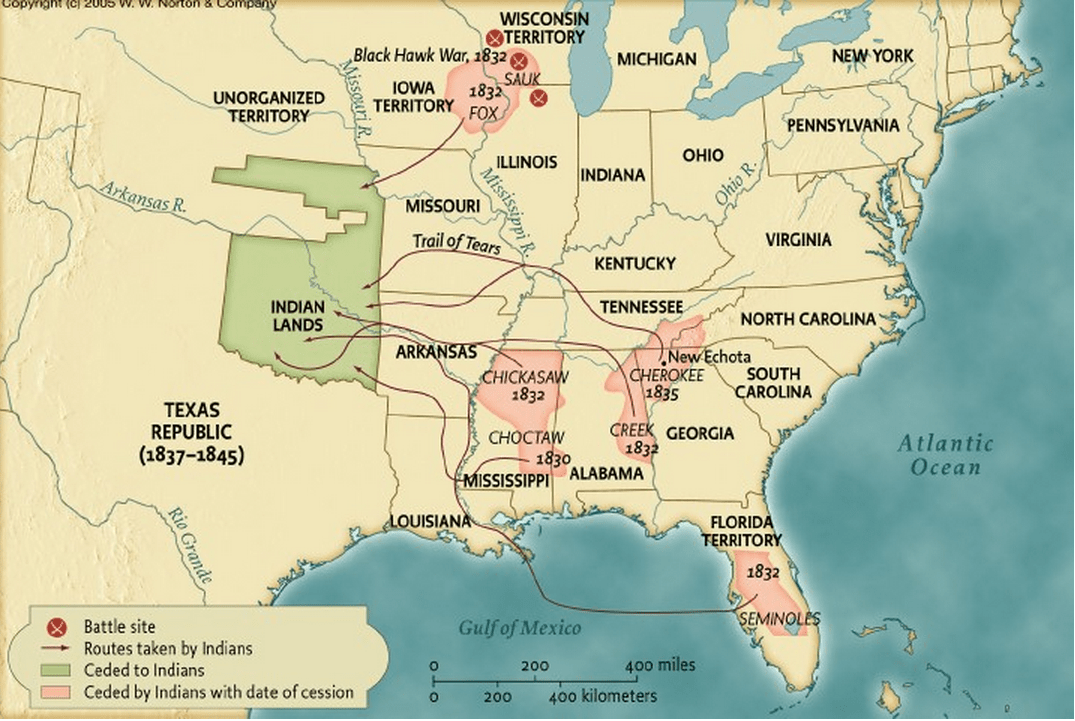

The most infamous and devastating consequence of the Indian Removal Act was the "Trail of Tears" – a collective term for the forced migrations of numerous Southeastern tribes, primarily the "Five Civilized Tribes": the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole.

- The Choctaw (1831-1833): The first to be forcibly removed, the Choctaw’s journey was marked by inadequate supplies, harsh weather, and disease, leading to thousands of deaths. Their removal set a grim precedent.

- The Creek (1836): Following a period of intense pressure and land cessions, a faction of the Creek resisted, leading to a brutal military roundup. Thousands were chained and marched, often without proper clothing or food, resulting in immense loss of life.

- The Chickasaw (1837-1838): Though they negotiated a more favorable treaty for their removal, they faced significant logistical challenges and disease, still suffering considerable losses.

- The Cherokee (1838-1839): The Cherokee’s story is perhaps the most widely known. Despite their sophisticated written language, constitutional government, and attempts to assimilate, they were targeted. In 1838, under the command of General Winfield Scott, over 16,000 Cherokee men, women, and children were rounded up at bayonet point, confined in stockades, and then forced to march over 1,000 miles, primarily on foot, during a harsh winter. An estimated 4,000 Cherokees died from disease, starvation, and exposure. Their route, and those of other removed tribes, are now collectively commemorated as the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail.

- The Seminole (1835-1842): The Seminole of Florida fiercely resisted removal, leading to the protracted and costly Second Seminole War, the longest and most expensive Indian war in U.S. history. Many Seminole remained in the Everglades, evading capture, while others were forcibly removed to Indian Territory.

These were not isolated incidents. Numerous other tribes across the U.S., including the Potawatomi, Ottawa, Sauk and Fox, Delaware, Shawnee, and Kickapoo, faced similar forced migrations. Later in the century, the Nez Perce, Navajo, and Apache also endured brutal forced marches and confinement as part of the broader policy of "Indian Wars" and reservation confinement. The map of forced removals extends far beyond the Southeast, etching a nationwide pattern of dispossession.

The Enduring Scars: Identity, Trauma, and Resilience

The impact of forced removals was catastrophic and multi-faceted.

- Demographic Collapse: The immediate consequence was a massive loss of life due to disease, starvation, exposure, and violence. Entire generations were decimated.

- Loss of Land and Resources: Tribes lost their ancestral lands, which were the foundation of their economic, spiritual, and cultural existence. This severed deep ties to sacred sites, hunting grounds, and agricultural fields.

- Cultural Disruption: Traditional governance structures, spiritual practices, languages, and social systems were severely disrupted or destroyed. The forced relocation to unfamiliar territories often placed disparate tribes in close proximity, leading to new tensions and challenges.

- Intergenerational Trauma: The trauma of removal—the fear, loss, violence, and profound grief—did not end with the journey. It became an intergenerational wound, affecting mental health, community cohesion, and economic stability for generations. The legacy of these removals continues to manifest in higher rates of poverty, health disparities, and social challenges within Native American communities today.

Yet, the map of forced removals is also a testament to incredible resilience and the enduring strength of Native American identity. Despite unimaginable adversity, Indigenous peoples survived. They rebuilt their communities in new lands, adapted, preserved their languages and ceremonies, and continued to fight for their rights and sovereignty. The experience of removal, while devastating, also forged a shared identity of survival and resistance, strengthening community bonds and a fierce determination to maintain their distinct cultures.

Traveling with Purpose: Engaging the Map Today

For the modern traveler and educator, understanding the Map of Native American Forced Removals is not just about recounting past injustices; it’s about engaging with a living history that continues to shape contemporary America.

- Responsible Tourism: When visiting areas along the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail or other sites significant to Native American history, travelers have a responsibility to approach these places with respect and humility. This means learning about the local Indigenous communities, acknowledging their history, and supporting their cultural preservation efforts.

- Educational Imperative: The map serves as a powerful educational tool, challenging romanticized narratives of American expansion and revealing the human cost of nation-building. It prompts us to consider the perspectives of those dispossessed and to understand the ongoing struggles for justice and recognition faced by Native American nations.

- Connecting Past and Present: Many Native American communities today actively work to preserve their histories, languages, and cultures. Visiting tribal museums, cultural centers, and participating in tribal events (when appropriate and invited) offers invaluable opportunities to learn directly from Indigenous voices and witness the vibrancy of contemporary Native American life.

- Recognizing Sovereignty: Understanding the forced removals highlights the fundamental issue of tribal sovereignty. Native American nations are not simply ethnic groups; they are distinct political entities with inherent rights to self-governance. The map underscores how these rights were systematically undermined and continue to be asserted today.

Conclusion: A Call to Remember

The Map of Native American Forced Removals is more than just lines on a page; it is a profound historical document etched in the land and in the collective memory of a people. It traces routes of profound loss, suffering, and injustice, but also pathways of incredible endurance, cultural survival, and unwavering identity. For anyone seeking to understand the true complexities of American history, to travel with a deeper sense of place, or to contribute to a more just future, this map is an essential guide. It compels us to remember the past, to acknowledge the ongoing legacy of these events, and to honor the resilience and enduring spirit of the Native American nations who continue to enrich the cultural tapestry of this continent. By engaging with this map, we not only learn history; we embrace a more complete and empathetic understanding of our shared human story.