The Living Map: Charting the Return of Native American Sacred Objects

Imagine a map not just of geographical features, but of cultural memory, historical trauma, and profound healing. This is the essence of a "Map of Native American Sacred Object Return." Far from being a mere static visualization, such a map charts a dynamic, ongoing journey of justice – tracing the path of irreplaceable cultural and spiritual treasures from museum shelves, private collections, and institutional storage back to the Indigenous communities from which they were taken. For the curious traveler and the discerning history enthusiast, understanding this map is to witness a powerful narrative of resilience, identity, and the painstaking work of decolonization.

The Map: A Visual Testament to Reclamation

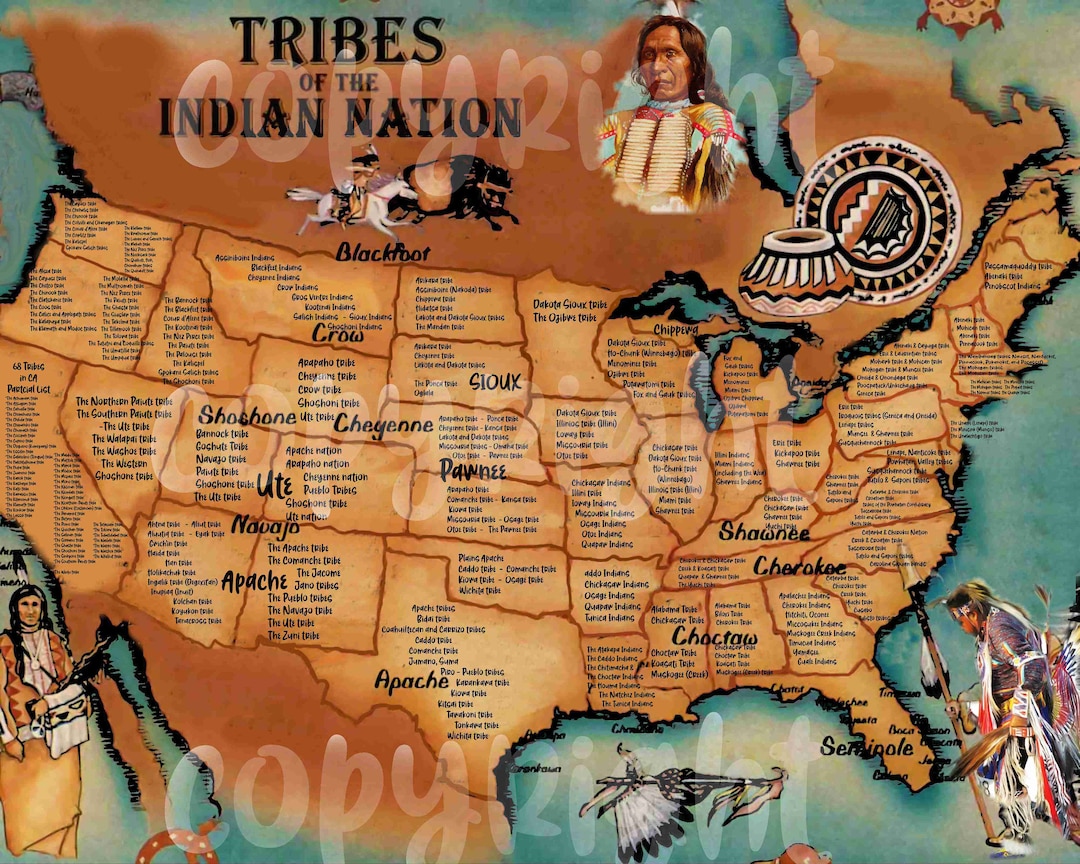

At its core, a map of sacred object return is a data visualization with deep spiritual resonance. Picture a map of North America, dotted with countless points. Each dot might represent a museum, university, or private collection that once held, or still holds, Native American sacred objects, funerary items, or ancestral remains. Lines then radiate from these dots, connecting them back to specific tribal lands – the true homes of these cultural patrimonies. Some lines might be thick and numerous, indicating significant successful repatriations; others might be thin, representing ongoing negotiations or even unresolved claims.

This map is not just a ledger of transactions; it’s a living document. It tells stories of objects that have been separated from their people for generations, sometimes centuries, and the arduous, often emotional, process of their homecoming. It highlights the sheer scale of cultural dispossession that occurred during colonization and the subsequent era of forced assimilation, but more importantly, it celebrates the victories of cultural revitalization. It visually underscores that these objects are not mere artifacts but living entities, vital to the spiritual health and continuity of Native nations.

Sacred Objects: More Than Mere Artifacts

To grasp the significance of their return, one must first understand what these "sacred objects" truly represent. In Western museum contexts, items are often categorized as "artifacts," "curiosities," or "art." But for Native American peoples, these are not inert historical relics. They are often living beings, imbued with spiritual power, used in ceremonies, or connected directly to ancestors. They embody tribal identity, history, laws, and cosmology.

Consider the diverse range of items classified under "sacred objects" or "cultural patrimony":

- Ceremonial Regalia: Masks, headdresses, pipes, staffs, and garments used in dances, rituals, and spiritual practices. These are not costumes but extensions of the wearer, often imbued with specific powers or representing ancestral spirits.

- Bundles and Effigies: Carefully wrapped collections of objects, often containing powerful spiritual items, medicines, or representations of deities or ancestors. These are frequently considered living beings that require specific care and respect.

- Ancestral Remains and Funerary Objects: The bones of ancestors themselves are paramount, along with the items buried with them to aid their journey into the afterlife. Their disturbance and removal cause profound spiritual and emotional trauma.

- Objects of Cultural Patrimony: Items that, by their nature, belong to the community as a whole rather than an individual. These might include wampum belts recording treaties, tribal medicine bundles, or items central to a nation’s origin stories and governance.

These objects are integral to maintaining spiritual balance, teaching history, transmitting traditional knowledge, and asserting cultural continuity. Their absence leaves a void, disrupting ceremonies, severing intergenerational connections, and hindering the full expression of tribal identity.

A History of Displacement and Dispossession

The need for a map of return stems directly from a painful history of displacement and dispossession. From the arrival of European colonizers, Native American lands, resources, and cultures were systematically targeted. As lands were seized, treaties broken, and populations decimated by disease and warfare, so too were cultural objects plundered.

During the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries, countless sacred items were acquired through unethical means:

- Looting and Battlefield Scavenging: After massacres or conflicts, items were often taken from the dead or from ransacked villages.

- Archaeological Excavation without Consent: Early archaeological practices often involved digging up ancestral burial sites and village ruins without permission or respect for Indigenous communities, removing human remains and associated grave goods.

- Forced Sales and Coercion: During periods of extreme poverty, forced relocation, or cultural suppression (like the boarding school era), Native people were often pressured or compelled to sell sacred items for survival, or saw them confiscated by government agents or missionaries aiming to eradicate traditional practices.

- Unethical Collecting by Anthropologists and Explorers: While some early ethnographers did important work, many also acquired objects under dubious circumstances, often prioritizing "collecting" over respecting cultural protocols or Indigenous ownership.

These objects then found their way into private collections, natural history museums, art museums, and university archives across the United States and globally. They were often displayed as curiosities, scientific specimens, or examples of "primitive art," entirely divorced from their living cultural contexts and spiritual significance. This institutionalization of stolen heritage further cemented the narrative of Native Americans as a "vanishing race," their cultures relegated to the past, rather than vibrant, enduring communities.

The Long Road to Repatriation: Legal and Ethical Frameworks

The tide began to turn in the late 20th century, largely due to sustained advocacy by Native American tribes themselves. This led to landmark legislation in the United States: the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990.

NAGPRA is a federal law that mandates the return of Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony by federal agencies and museums that receive federal funding to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated Native American tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations. This act was revolutionary because it legally recognized Indigenous claims to these items, shifting the burden of proof from tribes having to "buy back" their heritage to institutions being legally obligated to return it.

Key aspects of NAGPRA and the broader repatriation movement include:

- Consultation: Museums and federal agencies are required to consult with tribes to identify and facilitate the return of items.

- Inventory and Summary: Institutions must compile inventories of human remains and associated funerary objects, and summaries of unassociated funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony.

- Cultural Affiliation: Establishing the cultural link between the objects and a modern-day tribe is crucial, often requiring extensive research, oral histories, and expert testimony.

- International Efforts: Beyond NAGPRA, which is a US law, there are growing international efforts. The UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) affirms the right of Indigenous peoples to the return of their ceremonial objects and human remains. Many museums globally are also developing their own ethical guidelines and proactive repatriation policies, recognizing the moral imperative even where no specific law applies.

The process, however, is rarely simple. It involves painstaking research, legal challenges, bureaucratic hurdles, and often, emotional negotiations. Funding for tribes to identify, transport, and properly rehouse repatriated items can also be a significant challenge. Yet, each successful repatriation marks a profound moment of healing and justice.

Reclaiming Identity and Sovereignty: The Impact of Return

The return of sacred objects is far more than just the transfer of property; it is a powerful act of cultural revitalization, spiritual healing, and the affirmation of Indigenous sovereignty.

- Cultural Revitalization: When objects come home, they often bring with them dormant knowledge. Ceremonies that haven’t been performed for generations can be revived. Languages, songs, and stories connected to these items are relearned and retold. Elders, who may have only heard tales of these objects, can now share their presence with younger generations, fostering intergenerational learning and cultural continuity.

- Healing Historical Trauma: The prolonged absence of sacred items is a constant reminder of historical trauma – of violence, loss, and disrespect. Their return is a step towards mending these wounds, acknowledging past wrongs, and restoring dignity. It validates the spiritual beliefs and cultural practices that were once suppressed.

- Strengthening Tribal Sovereignty: Repatriation asserts the inherent right of Native nations to govern their own cultural heritage. It is an act of self-determination, demonstrating that tribes have the authority and capacity to care for their most sacred possessions according to their own traditions and laws. It reinforces their status as distinct, self-governing nations.

- Educational Impact: For the broader public, each repatriation story serves as a powerful educational tool, challenging colonial narratives and fostering a deeper understanding of Native American history, resilience, and ongoing cultural vitality. It moves the conversation beyond "artifacts" to "living culture."

The map of sacred object return, therefore, isn’t just about dots and lines; it’s about the tangible reconnection of people to their past, their present, and their future. It’s about communities regaining the spiritual tools necessary to practice their religions, tell their stories, and ensure the vibrancy of their unique identities for generations to come.

Beyond the Map: A Journey of Reconciliation

The journey charted by a map of Native American sacred object return is far from complete. While significant progress has been made, countless items and ancestral remains still await their homecoming. This map serves as a stark reminder of the work that remains to be done, but also as a beacon of hope and a testament to the unwavering determination of Native American communities.

For those interested in travel and history, this map offers a unique lens through which to understand North America. It encourages us to look beyond conventional tourist attractions and delve into the profound cultural landscapes shaped by Indigenous peoples. It invites us to recognize that true reconciliation involves not just acknowledging the past, but actively participating in the present-day efforts to restore justice and support Indigenous sovereignty.

Ultimately, the map of sacred object return is a living testament to the power of memory, the resilience of culture, and the enduring human spirit striving for healing and justice. It reminds us that history is not static, and that the path to a more equitable future is paved with acts of respectful return and genuine understanding.