The Unfurling Map: Native American Resilience and Survival

To speak of a "Map of Native American resilience and survival" is to speak not merely of geographical coordinates, but of a living, breathing testament to the enduring human spirit, a complex tapestry woven from centuries of history, identity, and an unyielding connection to the land. This is not a static document of the past, but an unfurling narrative of resistance, adaptation, and revitalization that continues to shape the present and future of Indigenous peoples across North America. For those seeking to understand the true depth of this continent’s history, this map offers profound lessons in identity, sovereignty, and the power of cultural persistence.

The Original Contours: A Pre-Contact World of Diversity

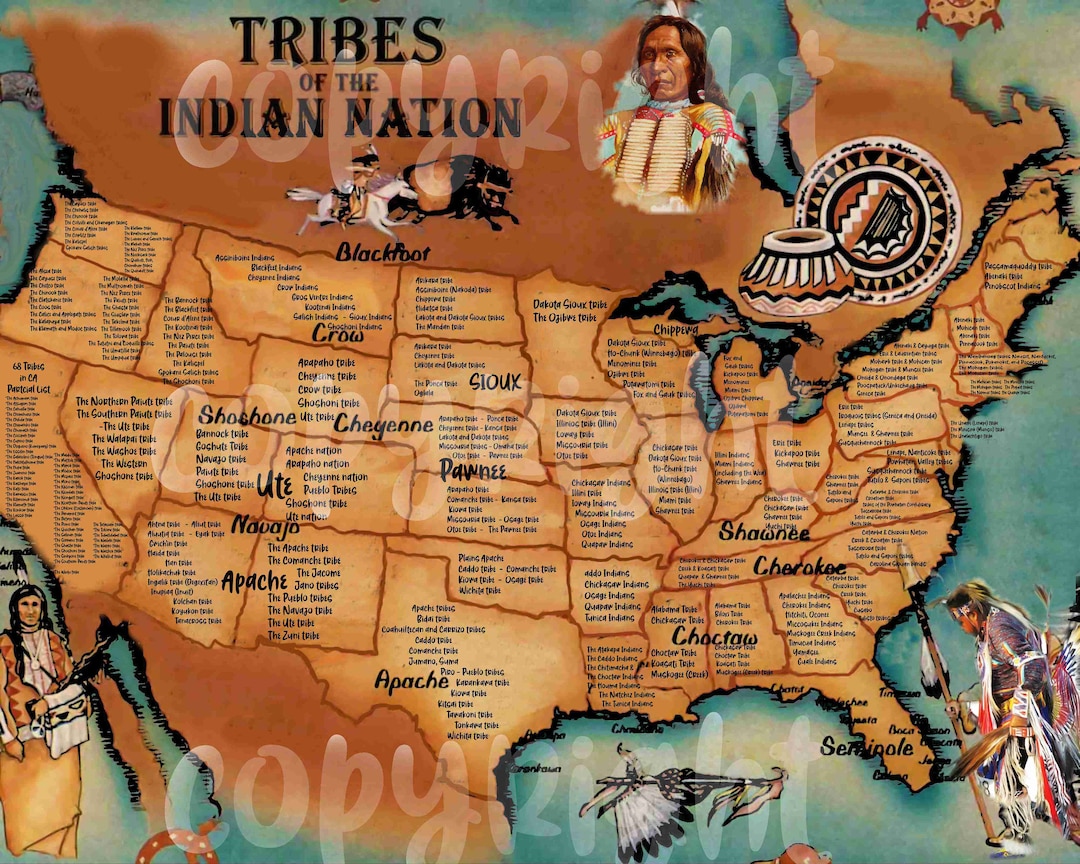

Before the arrival of European colonizers, the map of North America was a vibrant mosaic of hundreds of distinct Native American nations, each with its own language, governance, spiritual beliefs, economic systems, and intricate relationship with its ancestral lands. From the sophisticated agricultural societies of the Ancestral Puebloans in the Southwest, with their multi-story cliff dwellings and advanced irrigation, to the intricate trade networks of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) in the Northeast, who practiced a remarkable form of democratic governance, these societies were complex, dynamic, and deeply rooted.

The Inuit and Yupik peoples thrived in the Arctic, developing unparalleled knowledge of sea ice and marine mammals. The Plains tribes, like the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Comanche, moved with the buffalo herds, their lives intrinsically linked to these magnificent animals. Along the Pacific Northwest coast, nations like the Haida, Tlingit, and Kwakwakaʼwakw developed rich artistic traditions, monumental totem poles, and sophisticated social structures based on abundant marine resources. This pre-contact map was defined by ecological wisdom, sustainable practices, and a profound spiritual connection to place, where land was not a commodity but a sacred relative, the bedrock of identity and community. This era represents the initial contours of resilience – the established strength and adaptability that would face unprecedented challenges.

The Erasure and Resistance: A Map Under Siege

The arrival of European powers initiated a cataclysmic collision of worlds, profoundly altering the existing map. Disease, warfare, and the relentless pressure of colonial expansion led to massive population declines and the systematic dispossession of Indigenous lands. The narrative of "discovery" often overshadows the reality of invasion and the subsequent struggle for survival.

This period saw the forced removal of entire nations, epitomized by the Cherokee Nation’s Trail of Tears in the 1830s, where thousands perished during a brutal march from their ancestral lands in the Southeast to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Treaties, often signed under duress or outright fraud, were systematically broken, further eroding Indigenous land bases and sovereignty. The U.S. government’s policy of "Manifest Destiny" fueled a relentless push westward, leading to devastating conflicts like the Sand Creek Massacre and the Battle of Little Bighorn, where Native resistance fighters like Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse bravely defended their homelands.

Yet, even in the face of overwhelming odds, Native nations demonstrated immense resilience. Resistance wasn’t solely military; it was also cultural. Spiritual leaders continued ancient ceremonies in secret, languages were whispered in homes, and traditional knowledge was passed down through generations, often at great personal risk. The ability to maintain identity and cultural practices under such immense pressure forms a critical layer of the resilience map – a testament to an unyielding spirit that refused to be extinguished.

The Constricted Map: Reservations and Assimilation

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the map of Native America had been drastically redrawn. The vast majority of Indigenous peoples were confined to reservations – small, often infertile parcels of land, a fraction of their original territories. This policy aimed to break tribal cohesion and force assimilation into mainstream American society.

Perhaps the most insidious assault on Native identity came through the boarding school system. Children were forcibly removed from their families, forbidden to speak their native languages, practice their spiritual traditions, or wear their traditional clothing. The mantra "Kill the Indian, Save the Man" encapsulated the brutal intent of cultural genocide. The Dawes Act of 1887 further fragmented tribal lands by allotting individual parcels to Native Americans, with the "surplus" land then sold to non-Natives, resulting in massive land loss and the erosion of communal land ownership.

Despite these systematic attempts to erase their cultures, Native communities found ways to survive. Elders continued to teach sacred stories and songs in defiance. Languages, though suppressed, were often preserved in homes and among small groups. The reservation, intended as a tool of control, ironically became a crucible for a new form of communal resilience. It was on these constrained lands that communities rebuilt, adapted, and maintained the vital threads of their cultural heritage, ensuring the continuity of their identity against overwhelming external pressure. This period showcases the deep internal fortitude of Indigenous communities to adapt and persist even when their external world was dramatically altered.

Reclaiming the Map: Self-Determination and Cultural Renaissance

The mid-20th century marked a significant turning point, ushering in an era of self-determination. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, while flawed, halted the allotment policy and encouraged tribal self-governance. However, the subsequent "Termination" policies of the 1950s and 60s, which aimed to dissolve tribal governments and assimilate Native Americans fully, proved disastrous for many tribes, leading to poverty and the loss of federal recognition.

The Civil Rights movement of the 1960s ignited the "Red Power" movement, with groups like the American Indian Movement (AIM) advocating for treaty rights, tribal sovereignty, and cultural pride. Landmark events like the occupation of Alcatraz (1969-1971) and Wounded Knee (1973) brought national and international attention to Indigenous issues. These movements successfully pressured the U.S. government to reverse termination policies and embrace a new era of self-determination.

This period saw a powerful cultural renaissance. Native languages, once endangered, are now being revitalized through immersion schools and community programs. Traditional arts, ceremonies, and storytelling have experienced a resurgence. Tribal nations began asserting their sovereignty, establishing their own police forces, court systems, and healthcare facilities. The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988 provided a pathway for economic development, allowing many tribes to generate revenue for social services, education, and infrastructure, rebuilding their communities from within. This is the map being actively redrawn by Native hands, asserting agency and reclaiming narratives.

The Living Map: Contemporary Resilience and Future Horizons

Today, the map of Native American resilience and survival is a dynamic, evolving landscape. There are 574 federally recognized tribal nations in the United States, each a distinct sovereign government, alongside numerous state-recognized and unrecognized tribes. These nations are architects of their own futures, engaging in diverse forms of economic development—from renewable energy projects and sustainable agriculture to tourism and tech ventures—all aimed at strengthening their communities and preserving their cultural heritage.

Contemporary resilience manifests in many forms:

- Language Revitalization: Efforts to teach and preserve Indigenous languages, recognizing them as critical carriers of culture, worldview, and identity.

- Cultural Arts and Media: A burgeoning Native arts scene, literature, film, and music that shares Indigenous stories, challenges stereotypes, and celebrates cultural vibrancy.

- Environmental Stewardship: Many tribes are at the forefront of environmental protection, drawing on millennia of ecological knowledge to address climate change and advocate for sustainable land and water management, as powerfully demonstrated by movements like Standing Rock.

- Political Advocacy: Native leaders and activists continue to advocate for treaty rights, land back movements, and policies that address historical injustices and promote tribal sovereignty on local, national, and international stages.

- Health and Education Initiatives: Tribal nations are developing culturally relevant health programs and educational institutions that cater to the unique needs and perspectives of their communities, fostering self-sufficiency and well-being.

- Digital Presence: Indigenous communities are leveraging digital platforms to share their stories, connect globally, and educate the wider public about their histories and contemporary realities.

Despite these triumphs, challenges persist, including ongoing struggles for land and water rights, the impacts of historical trauma, economic disparities, and the need for greater representation and understanding in mainstream society. Yet, the persistent vibrancy of Native cultures, the determination to heal and thrive, and the unwavering commitment to ancestral lands underscore a resilience that is not merely survival, but a powerful, ongoing flourishing.

Engaging with the Map: A Call for Understanding and Respect

For those interested in travel and historical education, understanding this map of Native American resilience is crucial. It means moving beyond static historical accounts and recognizing Indigenous peoples as contemporary, dynamic societies with rich, living cultures.

- Support Tribal Economies: When traveling, seek out and support Native-owned businesses, artists, and cultural centers. Your engagement directly contributes to tribal self-sufficiency.

- Visit Tribal Lands Respectfully: Many tribal nations welcome visitors to their museums, cultural events, and natural sites. Always respect tribal laws, customs, and sacred spaces. Research specific protocols before visiting.

- Learn from Indigenous Voices: Seek out books, documentaries, and art created by Native Americans. Listen to their perspectives and challenge preconceived notions.

- Acknowledge Land: Understand whose ancestral lands you are on. Land acknowledgments are a small but significant step in recognizing the continuous presence and sovereignty of Indigenous peoples.

- Recognize Ongoing Struggles: Acknowledge that the fight for justice, sovereignty, and environmental protection continues.

The Map of Native American resilience and survival is not just a historical document; it is a living guide to understanding profound human strength, adaptability, and the enduring power of cultural identity. It reminds us that history is not past but present, and that the Indigenous peoples of North America are not relics of a bygone era, but vibrant, sovereign nations, continuing to shape the landscape – both geographical and cultural – of this continent. To truly see this map is to witness an extraordinary journey of persistence, a testament to the indomitable spirit of humanity.