>

The Unfolding Map: A Visual History of Native American Population Decline and Enduring Resilience

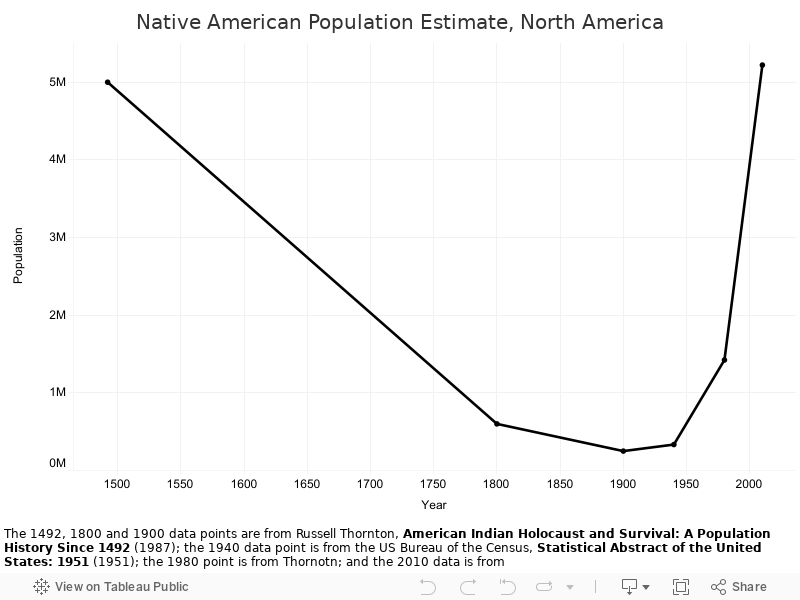

The history of the Americas is often told as a story of discovery and expansion, a relentless march westward. But beneath this narrative lies another, far more somber and profound story, etched vividly onto the very maps we use. It’s the story of the Indigenous peoples of this land, and how their presence, once vibrant and vast, dramatically diminished, then slowly began to recover. For any traveler or history enthusiast, understanding the "Map of Native American Population Decline" isn’t just about statistics; it’s about grasping the profound human cost of colonization and the astonishing resilience of cultures that refused to be erased.

This isn’t a mere cartographic representation of shrinking landmasses; it’s a living document of human experience—of thriving civilizations, catastrophic losses, forced migrations, and an enduring spirit. Let’s trace this powerful, often heartbreaking, yet ultimately inspiring journey.

The Pre-Columbian Tapestry: A Continent Teeming with Life

Before the arrival of Europeans, North America was not a pristine wilderness awaiting discovery, but a continent teeming with diverse, sophisticated societies. Estimates vary, but scholars suggest populations ranging from 2 million to 18 million people, organized into hundreds of distinct nations, tribes, and communities. From the agricultural marvels of the Cahokia mounds in the Mississippi Valley to the intricate irrigation systems of the Ancestral Puebloans in the Southwest, and the complex social structures of the Iroquois Confederacy in the Northeast, these societies had developed unique languages, spiritual beliefs, governance systems, and sustainable ways of life.

Imagine a map of this era: a kaleidoscopic array of territories, each representing a vibrant culture. The Chinook along the Pacific Northwest coast, the Lakota traversing the Great Plains, the Cherokee cultivating lands in the Southeast, the Lenape inhabiting the Mid-Atlantic—each occupied and managed vast swathes of land, connected by intricate trade routes and occasional conflicts, but undeniably the masters of their own destinies. Their identities were intrinsically tied to these ancestral lands, not just as property, but as sacred spaces, sources of sustenance, and the very foundation of their worldview.

The Cataclysm of Contact: Disease and Dispossession Begin

The arrival of Europeans, beginning with Columbus in 1492, marked the beginning of the most devastating demographic catastrophe in human history. It wasn’t primarily superior weaponry that decimated Indigenous populations in the initial centuries, but disease. Lacking immunity to European pathogens like smallpox, measles, influenza, and typhus, Native communities were ravaged. Epidemics swept across the continent, often preceding direct European contact, wiping out entire villages and sometimes even entire nations.

The impact on the map was immediate and terrifying. Whole regions became ghost lands, their populations decimated by waves of unseen invaders. While the physical borders of European colonies were still relatively small, the human landscape was already undergoing a radical, tragic transformation. This initial, largely involuntary, population decline laid the groundwork for subsequent waves of dispossession, weakening the ability of many tribes to resist the encroaching colonial powers.

Colonial Expansion and Warfare: A Shifting, Shrinking Reality

As European colonies expanded—first Spanish, then French, English, Dutch—the pressure on Native lands intensified. What began as trade relationships often devolved into conflict over resources, territory, and ideology. The Pequot War, King Philip’s War, the French and Indian War, and countless smaller skirmishes saw Native communities caught in the crossfire or deliberately targeted. Treaties were signed, often under duress, only to be broken as colonial hunger for land grew.

On our evolving map, this era shows European colonial boundaries pushing relentlessly inward, carving out territories from Indigenous lands. The once-fluid, vast territories of Native nations began to shrink, fragmented by colonial claims and the establishment of fortified settlements. The identities of these tribes, while still strong, were increasingly defined by their resistance to encroachment and their struggle to maintain their cultural integrity against overwhelming odds. The notion of land as a communal, sacred trust clashed violently with the European concept of private ownership and exploitation.

Manifest Destiny and Forced Removal: The Great Erasure

The formation of the United States accelerated the process of dispossession. The ideology of "Manifest Destiny"—the belief in America’s divine right to expand westward—provided a moral justification for seizing Native lands. The early 19th century saw a series of landmark policies, most notably the Indian Removal Act of 1830. This act led to the infamous "Trail of Tears," where the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole nations were forcibly marched thousands of miles from their ancestral homes in the Southeast to "Indian Territory" (present-day Oklahoma). Thousands died during these brutal forced migrations.

Visually, this period on our map is perhaps the most dramatic. Large, contiguous Native territories in the eastern United States vanished almost overnight, replaced by the checkerboard of states. The remaining Native presence was consolidated into smaller, often unfamiliar, and resource-poor "reservations" in the West. This wasn’t just a loss of land; it was an attempt to sever the deep spiritual and cultural ties Indigenous peoples had with their ancestral homelands, a fundamental assault on their very identity. The trauma of removal profoundly shaped the collective memory and identity of these nations for generations.

Assimilation and Allotment: The Assault on Culture and Community

Even after being confined to reservations, the assault on Native American identity and sovereignty continued. The latter half of the 19th century and early 20th century were dominated by policies of assimilation. The Dawes Act of 1887, also known as the General Allotment Act, aimed to break up communal tribal lands into individual plots. The "surplus" land, often the most valuable, was then sold off to non-Native settlers. This policy was designed to dismantle tribal structures, force Native Americans into Euro-American farming practices, and further reduce their land base.

Concurrently, a network of Indian boarding schools was established. Children were forcibly removed from their families, forbidden to speak their native languages, practice their traditions, or wear traditional clothing. The stated goal was "kill the Indian, save the man." The psychological and cultural damage inflicted by these schools was immense and continues to reverberate today.

On our map, this era shows the further fragmentation of reservations, with parcels of land falling into non-Native hands. The vibrant cultural territories of the past were now reduced to small, isolated islands, often surrounded by settler communities. The very fabric of Native identity, woven through communal land ownership and shared cultural practices, was deliberately targeted for unraveling.

The 20th Century: A Slow Recovery and Renewed Struggle

The 20th century brought some shifts. The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 granted Native Americans full US citizenship, though some states still denied them voting rights for decades. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 reversed some aspects of the Dawes Act, allowing tribes to re-establish self-governance and consolidate some lands. However, the mid-20th century also saw the disastrous "Termination Policy," which aimed to end the federal government’s recognition of tribes and their trust relationship, further dispossessing some nations of their land and resources.

Despite these legislative swings, the 20th century also witnessed a powerful resurgence of Native American activism and a renewed assertion of identity. The American Indian Movement (AIM) and other Red Power groups fought for civil rights, treaty enforcement, and cultural preservation. Landmarks like the occupation of Alcatraz in 1969 became symbols of this revitalized spirit.

While the physical map of Native land did not dramatically expand during this period, the map of identity and sovereignty began to strengthen. Tribes worked to reclaim their languages, revive spiritual practices, and rebuild their communities, often against immense socio-economic challenges inherited from centuries of oppression.

Modern Resilience: Reclaiming the Narrative

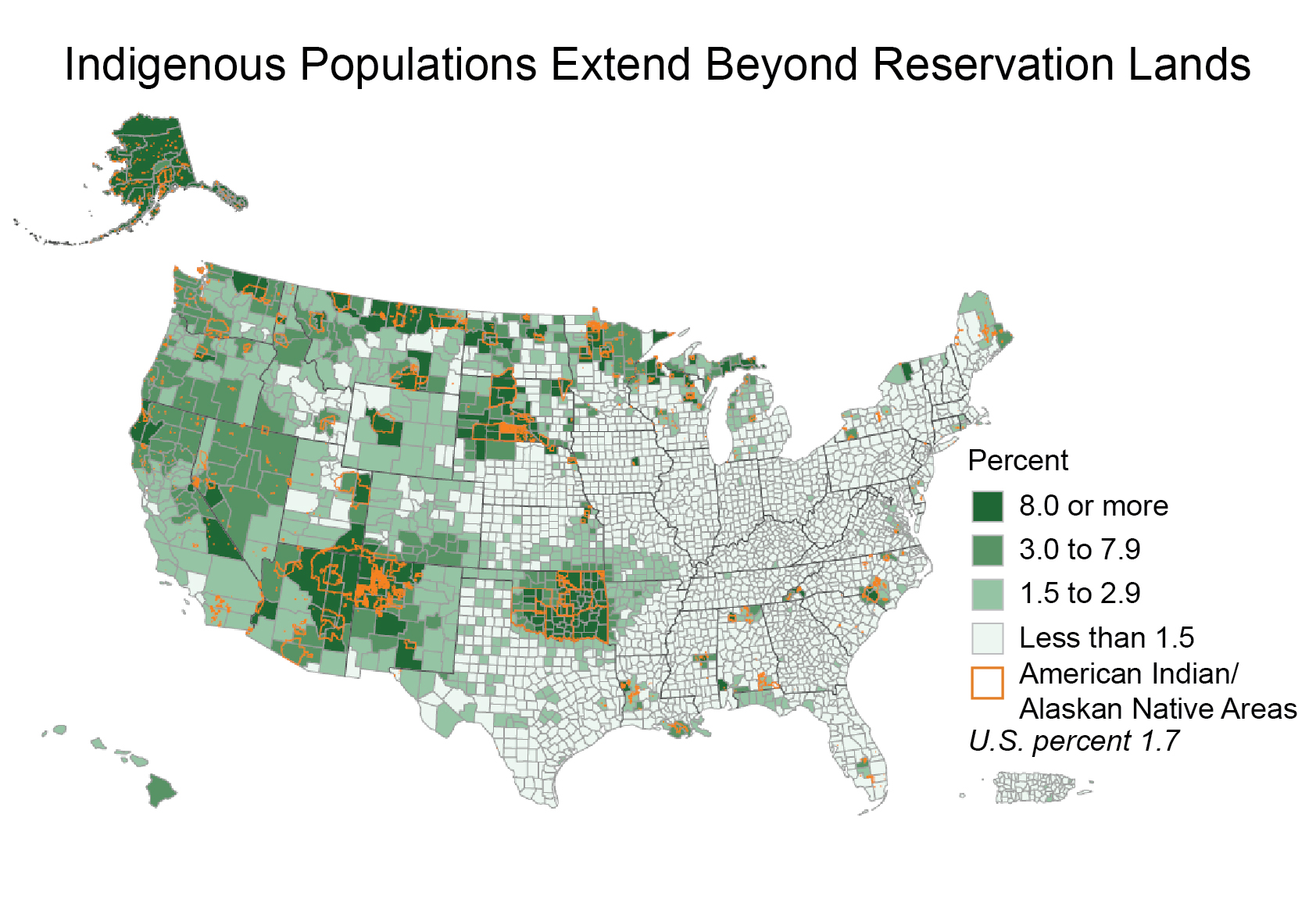

Today, the map of Native America tells a story not just of decline, but of extraordinary resilience and ongoing revitalization. While the land base remains a fraction of what it once was, the over 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States, along with numerous state-recognized and unrecognized tribes, are vibrant, self-governing nations. They are engaged in economic development, cultural preservation, language revitalization programs, and legal battles to protect their treaty rights and ancestral lands.

The struggle continues, as evidenced by movements like Standing Rock, where Indigenous nations and their allies stood united to protect water and sacred sites. These modern battles underscore the enduring connection between Native identity and land, and the ongoing fight for environmental justice and self-determination.

The Map Today: A Testament to Survival

The "Map of Native American Population Decline" is a powerful historical document. It charts the devastating impact of colonization, disease, warfare, and forced assimilation. But more profoundly, it charts the incredible journey of survival. From a continent-wide presence, to near-annihilation, to a steadfast and growing resurgence, the Indigenous peoples of North America have defied the odds.

For travelers and history enthusiasts, understanding this map means looking beyond the borders of states and acknowledging the sovereign nations within them. It means recognizing the profound wisdom embedded in Indigenous cultures and their sustainable relationship with the land. It means supporting tribal businesses, visiting tribal museums and cultural centers, and listening to the voices of Native peoples themselves.

The map of Native America is not just a relic of the past; it is a dynamic, living testament to the enduring spirit, identity, and sovereignty of the First Peoples of this continent. It challenges us to confront a difficult history, but also inspires us with the unwavering strength of human resilience and the vibrant future being built by Indigenous communities today. As we navigate this land, let us do so with awareness, respect, and a commitment to learning from the profound narratives held within these ancestral territories.

>