The Sacred Cartography: Unveiling the Map of Native American Ceremonial Grounds

A map of Native American ceremonial grounds is far more than a collection of geographical coordinates; it is a living document, a vibrant tapestry woven from millennia of spiritual practice, cultural identity, and profound connection to the land. For the traveler and the student of history alike, understanding this sacred cartography offers an unparalleled journey into the heart of Indigenous North America – a journey that challenges preconceptions, reveals astonishing human ingenuity, and underscores the enduring resilience of Native cultures. This article delves into the historical layers and identity-shaping power of these sites, guiding us to read this map not just with our eyes, but with our hearts and minds.

Defining the Sacred Landscape: More Than Just Sites

Before we embark on our exploration, it’s crucial to understand what constitutes a "ceremonial ground." These are not merely places where rituals occurred; they are often intricately designed landscapes, modified or chosen for their inherent spiritual power, astronomical significance, or strategic community value. They served as focal points for:

- Spiritual Practices: Healing ceremonies, vision quests, rites of passage, prayers, and offerings to the Creator and spirits.

- Community Gathering: Social cohesion, inter-tribal meetings, trade, storytelling, and the transmission of knowledge.

- Astronomical Observation: Alignments with solstices, equinoxes, and celestial events, reflecting a sophisticated understanding of the cosmos and its impact on earthly life and agricultural cycles.

- Political and Social Organization: Centers for governance, conflict resolution, and the reinforcement of tribal identity and social structures.

The forms these grounds take are as diverse as the tribes themselves: from monumental earthen mounds and elaborate stone structures to natural rock formations, sacred springs, and vast, open plazas. Each is a testament to unique cosmological beliefs and a shared reverence for the natural world.

A Journey Through Time: Pre-Columbian Grandeur

The historical depth of Native American ceremonial grounds stretches back thousands of years, long before European contact. These ancient sites reveal highly complex societies with advanced architectural, astronomical, and artistic capabilities.

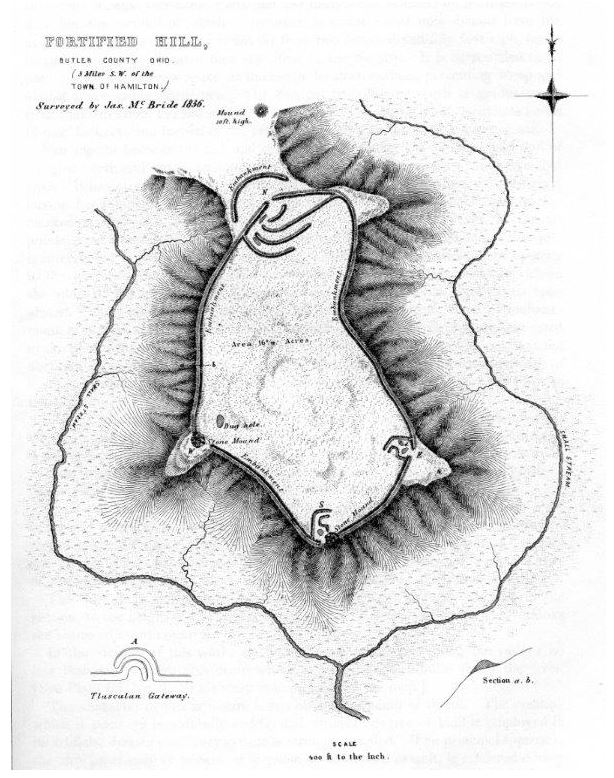

The Mound Builders: Earthworks of the East

Perhaps the most visible and awe-inspiring examples are the colossal earthworks of the Eastern Woodlands and Southeastern United States, created by various cultures collectively known as the "Mound Builders."

- Poverty Point (Louisiana, c. 1700-1100 BCE): One of the earliest and most enigmatic, this site features six concentric ridges separated by ditches, forming a semi-circle around a central plaza. While its exact function remains debated, its sheer scale and precise layout suggest a massive communal effort for ceremonial and gathering purposes, possibly tied to astronomical observations or intricate trade networks.

- Hopewell Culture (Ohio and surrounding states, c. 200 BCE – 500 CE): Known for their geometric earthworks—perfect circles, squares, and octagons—many aligned with lunar and solar cycles. Sites like the Newark Earthworks in Ohio, once encompassing over four square miles, demonstrate an astonishing level of engineering and astronomical knowledge. These complexes served as mortuary sites, ceremonial gathering places, and possibly pilgrimage destinations, featuring elaborate burial mounds filled with exotic grave goods, indicating widespread trade and a complex cosmology centered around death and regeneration.

- Mississippian Culture (Southeastern and Midwestern US, c. 800-1600 CE): Reaching its zenith with the city of Cahokia (near modern-day St. Louis, Illinois), the Mississippian culture built massive platform mounds, the largest being Monks Mound, which rivals the Great Pyramid of Giza in its base area. Cahokia was a sprawling urban center, home to tens of thousands, with a complex social hierarchy and a cosmology reflected in its city plan. Its central plazas, woodhenges (solar calendars made of timber posts), and temple mounds were focal points for elaborate ceremonies, feasts, and rituals connected to agriculture, the sun, and ancestor veneration.

- Serpent Mound (Ohio, c. 1070 CE): This iconic effigy mound, stretching over 1,300 feet, depicts a giant serpent uncoiling. Its head aligns with the summer solstice sunset, and its coils may mark other celestial events. It’s a powerful testament to the spiritual significance of celestial phenomena and the animal world for ancient peoples.

The Ancestral Puebloans: Stone Cities of the Southwest

In the arid landscapes of the American Southwest, the Ancestral Puebloans (formerly known as Anasazi) constructed breathtaking ceremonial centers within canyons and atop mesas.

- Chaco Canyon (New Mexico, c. 850-1250 CE): A UNESCO World Heritage Site, Chaco was a major regional center of culture, trade, and ceremony. Its "Great Houses" like Pueblo Bonito, Chetro Ketl, and Hungo Pavi were multi-story masonry structures with hundreds of rooms and numerous kivas—circular, subterranean chambers integral to Pueblo spiritual life. These kivas, ranging from small family units to massive "Great Kivas," served as places for ceremonies, council meetings, and spiritual introspection. The entire canyon was connected by an intricate road system, hinting at its role as a pilgrimage destination and the heart of a vast ceremonial network. Many structures incorporated precise astronomical alignments, demonstrating a deep understanding of the cosmos.

- Mesa Verde (Colorado, c. 600-1300 CE): Famous for its cliff dwellings, Mesa Verde also features numerous ceremonial structures. The kivas here, often integrated into the multi-story cliffside villages, were crucial for maintaining spiritual and community life in challenging environments. The careful planning and defensive locations of these sites reflect not only practical considerations but also a profound connection to the sacredness of their high-desert homes.

The Great Plains: Medicine Wheels and Sacred Sites

On the vast plains, ceremonial grounds often took on different forms, reflecting nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyles.

- Medicine Wheels: Stone circles found across the Great Plains, such as the Bighorn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming, often feature spokes radiating from a central cairn. These structures are believed to have served as astronomical observatories, aligning with solstices and specific stars, used for ceremonies, vision quests, and as calendrical tools. Their precise functions varied, but their spiritual significance as places of power and connection to the cosmos is undeniable.

- Vision Quest Sites: Isolated mountains, rock formations, and specific groves were used for individual vision quests, a transformative spiritual journey to seek guidance and power from the spirit world.

The Cataclysm and Resilience: Post-Contact Era

The arrival of Europeans in the late 15th century initiated a devastating period for Native American peoples and their sacred sites. Disease, warfare, forced displacement, and deliberate cultural suppression led to the destruction, desecration, or abandonment of countless ceremonial grounds.

- Disease and Depopulation: Epidemics ravaged Indigenous populations, leading to the collapse of complex societies like the Mississippians, whose ceremonial centers lay silent and overgrown.

- Land Seizure and Displacement: As European settlers expanded, ancestral lands were seized, and tribes were forcibly removed from their traditional territories. This not only dispossessed them of their homes but also severed their spiritual ties to the land and their ceremonial sites. The Trail of Tears, for example, saw the removal of Southeastern tribes from lands where their ancestors had built impressive mound complexes.

- Cultural Suppression: Colonial powers and later the U.S. government actively sought to eradicate Native religions and ceremonial practices, viewing them as "pagan" or obstacles to "civilization." Practices like the Sun Dance were outlawed, and children were sent to boarding schools designed to strip them of their cultural identity. Many sacred sites were either destroyed, built over, or repurposed.

Despite this relentless assault, Indigenous peoples demonstrated incredible resilience. Ceremonies continued in secret, traditions were passed down orally, and the memory of sacred sites endured. The spiritual connection to the land proved unbreakable, forming a core element of Native identity even in the face of immense adversity.

Contemporary Significance: A Living Heritage

Today, the map of Native American ceremonial grounds is not merely a historical artifact; it is a vibrant, living heritage that continues to shape Indigenous identity and spiritual practice.

- Cultural Revitalization: There has been a powerful resurgence of interest in traditional ceremonies, languages, and cultural practices. Tribes are actively reclaiming and revitalizing their ceremonial grounds, using them once again for traditional dances, healing rituals, and community gatherings. Powwows, Sun Dances, Sweat Lodge ceremonies, and various other cultural expressions are thriving.

- Identity and Sovereignty: These sites are central to tribal identity and sovereignty. They are tangible links to ancestors, proof of long-standing occupancy, and symbols of cultural continuity. The fight for the protection and repatriation of sacred sites is an ongoing struggle, highlighting the deep emotional and spiritual connection Indigenous peoples have to these lands.

- Legal Protections: Legislation like the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in the U.S. has been instrumental in protecting sacred sites and facilitating the return of ancestral remains and cultural items to their rightful communities. However, battles over land rights and the protection of sacred places from development (e.g., Standing Rock, Bears Ears) continue to be critical issues.

- Education and Awareness: These sites serve as powerful educational tools, challenging dominant historical narratives and fostering a deeper understanding of Indigenous perspectives. They are crucial for teaching younger generations about their heritage and for educating the broader public about the rich and complex history of North America.

Navigating the Sacred Cartography: A Traveler’s and Learner’s Guide

For those drawn to explore the map of Native American ceremonial grounds, whether virtually or physically, a profound sense of respect, humility, and a willingness to learn are paramount.

- Respect the Sacredness: Many of these sites, even those open to the public, remain active places of worship and spiritual practice. Approach them with reverence, understanding that they are not mere tourist attractions but living cultural landscapes.

- Seek Permission and Guidance: If visiting a site on tribal land, always seek permission from the relevant tribal authorities. Many sites are not open to the public, or require specific permits or guides. Support Indigenous-led tourism initiatives where available.

- Observe and Listen: When visiting, observe any posted rules, stay on designated paths, and avoid disturbing any features or leaving anything behind. Engage with interpretive materials provided by tribal nations or reputable organizations. Listen to Indigenous voices, stories, and perspectives—they offer the most authentic understanding of these places.

- Leave No Trace: This extends beyond physical litter to respecting the spiritual integrity of the site. Do not take artifacts, rocks, or any natural elements.

- Challenge Stereotypes: Use your visit as an opportunity to move beyond simplistic or romanticized notions of Native Americans. Recognize the diversity of cultures, histories, and contemporary realities.

- Support Indigenous Communities: Your interest and respectful engagement can contribute to the economic well-being and cultural preservation efforts of Native nations.

Conclusion: An Enduring Legacy

The map of Native American ceremonial grounds is a testament to the enduring human spirit, a narrative etched into the very earth. It reveals societies of remarkable complexity, spiritual depth, and an intrinsic understanding of their place within the cosmos. From the monumental earthworks of Cahokia to the intricate kivas of Chaco Canyon and the celestial alignments of the Medicine Wheels, these sites are not just relics of the past; they are vibrant symbols of Indigenous identity, resilience, and an unbroken connection to ancestral lands.

To engage with this sacred cartography is to embark on a journey of profound discovery – one that promises to enrich our understanding of history, challenge our perspectives, and inspire a deeper appreciation for the diverse and enduring cultures that have shaped, and continue to shape, the North American continent. It is an invitation to witness the living heart of Indigenous America, to listen to the whispers of the past, and to recognize the sacred wisdom that continues to resonate from these hallowed grounds.