Imagine a map. Not one with national borders or state lines, but an intricate, invisible cartography etched by centuries of history, law, and deep cultural connection: the map of Native American water rights. For those embarking on a journey through North America, whether physically or intellectually, understanding this hidden landscape is paramount. It’s not merely a legalistic curiosity; it’s a living testament to sovereignty, identity, and the enduring struggle for justice, crucial for appreciating the rich tapestry of Indigenous nations. This isn’t just about who gets to drink from a river; it’s about who gets to be.

The Ancient Tapestry: Water as Life and Identity Before Contact

Long before European explorers charted rivers and claimed lands, Indigenous peoples across North America lived in an intimate, reciprocal relationship with water. For thousands of years, water was not a commodity to be owned or exploited, but a sacred relative, the lifeblood of their communities, cultures, and ecosystems. From the vast salmon runs of the Pacific Northwest, sustaining nations like the Nez Perce and Salish, to the arid lands of the Southwest where the Hopi and Navajo perfected sophisticated dryland farming and water harvesting techniques, water was intrinsically woven into every aspect of existence.

Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) guided their stewardship. Tribes managed watersheds holistically, understanding the intricate connections between forests, springs, rivers, and the health of all living things. Ceremonies honored water, prayers were offered for rain, and intricate social structures ensured equitable access and sustainable use. Identity was often tied directly to specific bodies of water – a river might be considered an ancestor, a lake a sacred place of healing, a spring a source of spiritual power. To understand this deep, pre-contact relationship is to grasp the profound disruption that followed.

The Collision of Worlds: European Arrival and the Commodification of Water

The arrival of European settlers brought a radically different worldview. Driven by doctrines of discovery and manifest destiny, they saw land and water as resources to be conquered, owned, and exploited for economic gain. The concept of "prior appropriation" – "first in time, first in right" – became the cornerstone of Western water law, granting water rights based on who first diverted and used the water, regardless of ancestral claims. This legal framework directly clashed with Indigenous traditions of shared stewardship and collective access.

As the United States expanded westward, treaties were signed, often under duress, ceding vast tracts of land. While many treaties explicitly mentioned hunting, fishing, and gathering rights, the critical element of water, essential to exercising these rights and sustaining life on the newly designated reservations, was often left unstated or vaguely implied. The irony was bitter: tribes were often forcibly removed from their fertile homelands to arid, marginalized lands, where access to water became a matter of survival, yet their fundamental right to it was systematically denied or overlooked by the encroaching settler society.

The Legal Bedrock: The Winters Doctrine (1908)

The pivotal moment in Native American water rights came with the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Winters v. United States in 1908. The case involved the Fort Belknap Indian Community in Montana, whose agricultural livelihood was threatened by upstream non-Indian irrigators diverting water from the Milk River. The Court ruled that when the Fort Belknap Reservation was established by treaty in 1888, it implicitly reserved enough water from the Milk River to fulfill the reservation’s purposes, specifically to establish a permanent homeland and allow the tribe to develop an agricultural economy.

The Winters Doctrine established several critical principles:

- Reserved Rights: When Congress creates an Indian reservation, it implicitly reserves sufficient water to achieve the purposes for which the reservation was established.

- Priority Date: These reserved water rights have a priority date as of the creation of the reservation, making them "senior" to most non-Indian water rights established later under state law.

- Unquantified Rights: Initially, the Winters ruling did not quantify the exact amount of water reserved, leaving that to be determined later. This ambiguity became a source of significant conflict for decades.

The Winters Doctrine was a monumental victory, affirming that Native American water rights were inherent, federal, and pre-dated many state-granted rights. However, it also marked the beginning of a long, arduous struggle for tribes to quantify, defend, and utilize these rights.

The Era of Conflict and Litigation: From Courts to Compacts

For much of the 20th century, the Winters Doctrine remained largely theoretical for many tribes. State governments, powerful agricultural interests, and growing urban centers continued to appropriate water under state law, often ignoring or challenging tribal claims. Tribes faced immense obstacles: the burden of proving their water needs, the prohibitive costs of litigation, and the political opposition from entrenched non-Indian water users.

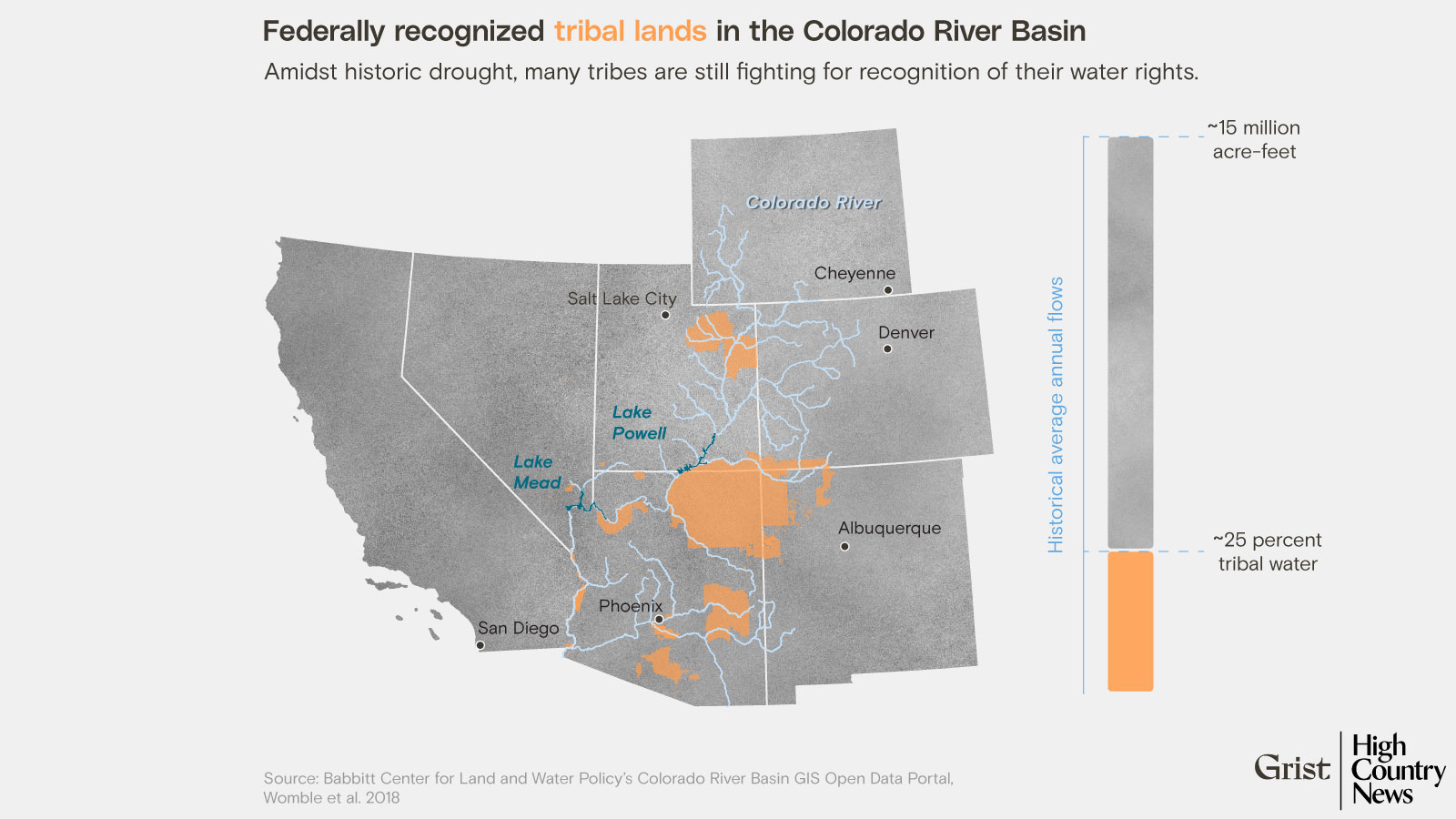

Major rivers like the Colorado, Columbia, and Missouri became battlegrounds. Cases like Arizona v. California (1963) affirmed tribal reserved rights to the Colorado River, but quantifying these rights and ensuring their delivery remained complex. On the Columbia River, tribes like the Yakama, Umatilla, Warm Springs, and Nez Perce fought tirelessly to protect their treaty-guaranteed fishing rights, which were inextricably linked to sufficient instream flows and healthy salmon populations. These battles were not just legal; they were existential, representing a fight for cultural survival against dams, diversions, and pollution.

In recent decades, there has been a shift towards negotiated settlements and water compacts, often facilitated by the federal government. These agreements, while complex and sometimes requiring tribes to compromise, offer a path to certainty for both tribal and non-tribal water users. They involve extensive research, hydrological studies, and political negotiation, but they can provide tribes with quantified water rights, funding for infrastructure, and a seat at the table in regional water management. Examples include the Navajo Nation’s ongoing efforts to quantify their rights to the Colorado River Basin and the numerous settlements reached by tribes in states like Montana and Washington.

Water as Identity, Sovereignty, and Self-Determination

Beyond economic and agricultural uses, water rights are fundamental to Native American identity, cultural practice, and sovereignty. For many tribes, water is sacred, a living entity with spiritual significance. Fishing, hunting, and gathering practices, guaranteed by treaty, depend entirely on healthy ecosystems and sufficient water flows. Ceremonies, traditions, and languages are often rooted in specific places and their waters. Denying access to water, or allowing its degradation, is not just an economic loss; it is an assault on cultural heritage, spiritual well-being, and the very fabric of identity.

The fight for water rights is, therefore, a fight for self-determination. Secure water rights enable tribes to manage their own resources, pursue economic development on their own terms, and ensure the health and well-being of their communities. It allows them to assert their inherent sovereignty over their lands and resources, rather than being dictated by state or federal authorities. This self-determination extends to environmental protection; many tribes are now leading the way in advocating for sustainable water management, watershed restoration, and climate resilience, drawing on their ancient wisdom and modern scientific understanding.

The federal government, through its "trust responsibility" to Native American tribes, has a legal and moral obligation to protect tribal assets, including water rights. While this responsibility has often been poorly fulfilled, it remains a critical legal lever for tribes seeking to assert their claims.

The Modern Landscape: Challenges and Progress

Today, the map of Native American water rights continues to evolve, facing new and intensifying challenges:

- Climate Change: Droughts are becoming more frequent and severe, particularly in the arid West, exacerbating competition for scarce water resources. Tribal communities, often located in vulnerable areas, are disproportionately impacted.

- Aging Infrastructure: Many reservations lack adequate water infrastructure, leading to boil water advisories, lack of running water, and reliance on contaminated sources. The fight for clean, safe drinking water is a pressing human rights issue on many reservations.

- Continuing Litigation and Negotiation: While settlements are becoming more common, many tribes are still engaged in protracted legal battles to quantify and protect their water rights.

- Environmental Justice: The intersection of water rights with environmental justice is increasingly evident, as tribal communities often bear the brunt of pollution from industrial agriculture, mining, and energy extraction.

Despite these challenges, there is also significant progress. Tribes are increasingly asserting their roles as sovereign nations in water governance. They are developing their own water codes, engaging in regional planning, and forming inter-tribal alliances to advocate for their collective interests. They are also at the forefront of innovative conservation and restoration efforts, demonstrating leadership in sustainable resource management.

Mapping the Unseen: What a "Water Rights Map" Reveals

If you could visualize this map of Native American water rights, it wouldn’t be a static image. It would be a dynamic, pulsating network of rivers, aquifers, and streams, overlaid with layers of history, law, and cultural meaning.

- It would highlight areas of historical injustice: Where rivers were diverted, lands desiccated, and communities displaced.

- It would illuminate areas of ongoing struggle: Where tribes continue to fight for their legal and inherent rights against powerful external interests.

- It would showcase pockets of triumph and resilience: Where tribes have successfully asserted their sovereignty, secured their water, and revitalized their communities and ecosystems.

- It would reveal the profound disparities: Between areas with abundant, secure water and those facing chronic scarcity and contamination.

- Crucially, it would connect the physical landscape to human stories: Of survival, resistance, and the enduring connection between people and place.

For the traveler and student of history, understanding this unseen map transforms a journey. A river is no longer just a scenic waterway; it becomes a lifeline, a treaty boundary, a site of spiritual significance, a battleground for justice. A visit to a tribal nation becomes an opportunity to witness living history, to understand the deep-seated connections between land, water, and identity, and to appreciate the ongoing efforts of Indigenous peoples to protect their heritage and secure their future.

Conclusion: An Ongoing Journey of Acknowledgment and Respect

The map of Native American water rights is a testament to the enduring sovereignty of Indigenous nations and their profound relationship with the natural world. It is a story of legal battles, broken promises, but also of incredible resilience, cultural strength, and a persistent fight for self-determination. For anyone seeking to truly understand the history and identity of North America, engaging with this complex, vital issue is essential. It calls for more than just recognition; it demands respect, informed engagement, and a commitment to justice for the original stewards of this land and its life-giving waters. As you travel, remember that every river, every lake, every drop of water tells a story – and many of those stories are deeply, profoundly Indigenous.