Ancient Roots, Modern Wisdom: Unearthing Native American Resource Management

Forget the romanticized image of untouched wilderness, a pristine landscape untouched by human hands. This widely held misconception, often projected onto Indigenous cultures, fundamentally misunderstands the sophisticated, intentional, and profoundly effective resource management practices that shaped North America for millennia before European arrival. The true "map" of Native American resource management isn’t just a physical representation of tribal territories; it’s a living, breathing blueprint of ecological knowledge, spiritual connection, and sustainable interaction woven into the very identity of diverse peoples.

This article delves into this complex tapestry, exploring how Indigenous nations across the continent managed their environments, not as owners, but as stewards. Their history and identity are inextricably linked to the land, offering invaluable lessons for today’s pressing environmental challenges.

The "Map" as a Living System: Beyond Borders

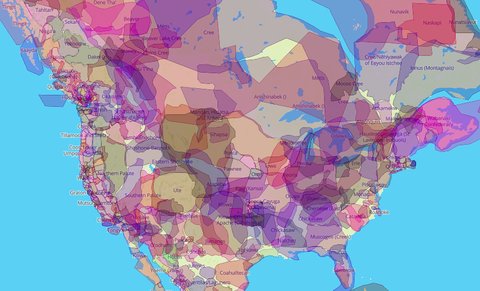

The concept of a "map of native tribe related to resource management" immediately brings to mind geographical areas. While distinct tribal territories certainly existed, delineated by natural features and cultural agreements, the true map of Indigenous resource management is far more nuanced. It’s a cognitive map, an intricate web of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) passed down through generations, outlining not just where resources were, but how they functioned, when they should be harvested, and who was responsible for their care.

This "map" was dynamic, adapting to changing climates and ecological shifts. It encompassed:

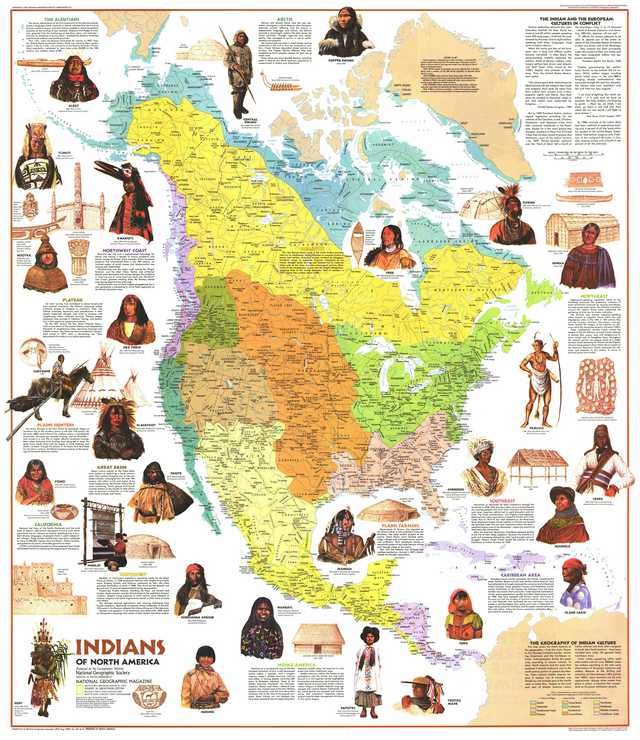

- Ecological Zones: From the arid deserts of the Southwest to the lush forests of the Northeast, the vast prairies of the Great Plains to the rich coastal ecosystems of the Pacific Northwest, each region presented unique challenges and opportunities. Indigenous peoples developed highly specialized management techniques tailored to their specific environments.

- Resource Distribution: Knowledge of where specific plants grew, where game migrated, where fish spawned, and where essential minerals could be found was meticulously cataloged and shared. This wasn’t merely about finding food; it was about understanding the entire life cycle and interconnectedness of these resources.

- Cultural and Spiritual Significance: Every resource, every landscape feature, held spiritual meaning. The relationship with the land was one of reciprocity and respect, not exploitation. This spiritual dimension underpinned all management decisions, ensuring practices were sustainable and honored the spirit of the land.

- Social and Political Boundaries: While resources were often shared or traded, specific tribal groups maintained primary stewardship over certain areas or resource types, developing unique cultural protocols for their management.

History and Identity: A Deep Connection to Place

For Indigenous peoples, identity is rooted in place. Clan structures, origin stories, ceremonies, and languages are often tied directly to specific landscapes, plants, and animals. This deep, ancestral connection fostered an intimate understanding of their environment over thousands of years – a timeline far exceeding modern scientific observation.

The Principles of Indigenous Resource Management:

- Reciprocity and Relationality: The core principle. The land and its inhabitants are not separate entities but relatives. One does not "take" without "giving back." This could manifest as prayers, offerings, or ensuring sustainable practices for future generations. Resources were viewed as gifts, not commodities.

- Long-Term Sustainability: Decisions were made with the seventh generation in mind. Short-term gains were always weighed against long-term ecological health and cultural survival. This inherent understanding led to practices that maintained or even enhanced biodiversity and ecosystem resilience.

- Adaptive Management: Indigenous systems were not static. Through continuous observation, experimentation, and oral tradition, practices evolved. If a particular method proved detrimental or less effective, it was adjusted.

- Holistic Understanding (TEK): Traditional Ecological Knowledge encompasses a deep understanding of complex ecological relationships, often expressed through stories, ceremonies, and practical skills. It integrates spiritual, cultural, and scientific knowledge.

- Community-Based Decision Making: Resource management was often a communal endeavor, with decisions made collectively, ensuring the benefit of the entire community and future generations.

Examples of Sophisticated Management Across the Continent:

1. Forest Management: The Art of Fire (California & Eastern Woodlands)

Long before Smokey Bear, Indigenous peoples across North America actively managed forests with fire. Tribes like the Karuk, Yurok, and Hupa in California, and various nations in the Eastern Woodlands, practiced controlled burns. These weren’t random acts; they were precise, intentional fires conducted at specific times of year.

- Benefits:

- Prevented Catastrophic Wildfires: By burning off underbrush and deadfall, smaller, cooler fires prevented the accumulation of fuel that leads to devastating crown fires.

- Enhanced Biodiversity: Fire promotes the growth of fire-adapted plants, encourages seed germination, and creates diverse habitats.

- Increased Food Resources: Many edible plants (berries, acorns, fungi) thrive after fire, improving forage for game animals.

- Facilitated Travel & Hunting: Open understories made travel easier and improved visibility for hunting.

- Supported Basketry & Craft Materials: Specific plant species used for basket weaving or tool making were often managed through burning.

The suppression of these practices by European settlers, who viewed all fire as destructive, led to the dense, overgrown forests we see today, contributing to the intensity of modern wildfires.

2. Water Management: From Desert Gardens to Riverine Weirs (Southwest & Pacific Northwest)

Water, the most precious resource, was managed with incredible ingenuity.

- The Ancestral Puebloans and Hohokam (Southwest): Developed extensive irrigation systems, including canals stretching for miles, to divert river water to their agricultural fields. They built check dams and terraces to slow runoff and retain moisture in an arid environment, cultivating corn, beans, and squash. The O’odham (Pima) people continued and refined these systems, creating verdant desert oases.

- Chinook, Kwakwaka’wakw, and other Coastal Nations (Pacific Northwest): Managed abundant salmon runs with sophisticated weir systems. These temporary structures allowed fish to pass upstream to spawn but could be selectively blocked to harvest enough for immediate needs and preservation, ensuring plenty of fish made it to the spawning grounds to replenish stocks. Their spiritual ceremonies around the first salmon run emphasized respect and sustainable harvesting.

3. Wildlife Management: The Bison and Beyond (Great Plains & Northeast)

Indigenous peoples understood the life cycles and behaviors of game animals intimately.

- Plains Nations (Lakota, Cheyenne, Crow): Their entire culture revolved around the bison. Rather than indiscriminate slaughter, hunts were communal and strategic, often involving sophisticated drives that herded bison into corrals or over cliffs. Every part of the animal was used – meat for food, hides for shelter and clothing, bones for tools, tendons for thread. This holistic use demonstrated profound respect and prevented waste, ensuring the herds remained healthy. They also understood the bison’s role in maintaining prairie ecosystems.

- Eastern Woodlands (Iroquois, Wampanoag): Managed deer, elk, and beaver populations through seasonal hunting, selective harvesting, and by maintaining diverse habitats through controlled burns. They understood the concept of carrying capacity and avoided overhunting.

4. Plant Management: Food Forests and Polyculture (Across the Continent)

Indigenous agriculture and plant gathering were far more complex than simple foraging.

- The "Three Sisters" (Iroquois, Cherokee, and many others): A prime example of polyculture, where corn, beans, and squash were grown together. Corn provided a stalk for beans to climb, beans fixed nitrogen in the soil, and squash leaves shaded the ground, suppressing weeds and retaining moisture. This created a self-sustaining, nutrient-rich system.

- "Wild" Food Cultivation: Many seemingly "wild" landscapes were, in fact, carefully cultivated food forests. Indigenous peoples selectively harvested, pruned, transplanted, and propagated desired plant species, effectively enhancing their abundance and productivity over time. This included berries, nuts, root crops, and medicinal herbs.

The Impact of Colonization and Resurgence

The arrival of European settlers dramatically disrupted these sustainable systems. Driven by different philosophies of land ownership (private property vs. communal stewardship) and resource use (extraction for profit vs. sustainable living), colonizers:

- Forcibly Removed Tribes: Separating Indigenous peoples from their ancestral lands severed their connection to traditional knowledge and management practices.

- Suppressed Traditional Practices: Controlled burns were outlawed, "primitive" agricultural methods were replaced by monoculture, and ceremonial practices linked to land stewardship were forbidden.

- Introduced Destructive Practices: Clear-cutting, unsustainable hunting for market (e.g., beaver pelts, buffalo hides), and intensive farming without regard for soil health rapidly degraded ecosystems.

- Imposed Artificial Borders: The creation of reservations often fragmented traditional territories, making holistic resource management difficult.

Despite this devastation, Indigenous knowledge persisted. Many practices went underground, passed down secretly through families. Today, there is a powerful resurgence. Tribal nations are reclaiming their sovereignty and actively revitalizing TEK. From reintroducing controlled burns to restoring native fisheries and practicing traditional agriculture, Indigenous communities are demonstrating that their ancient wisdom offers vital solutions to modern environmental crises.

Modern Relevance: A Blueprint for the Future

The "map" of Native American resource management is not merely a historical artifact; it is a dynamic, actionable blueprint for addressing some of the most pressing issues of our time:

- Climate Change Mitigation: Traditional fire management reduces carbon emissions from mega-fires, and diverse agricultural systems are more resilient to extreme weather.

- Biodiversity Preservation: Indigenous practices often enhance biodiversity, demonstrating how humans can live in harmony with, rather than at the expense of, the natural world.

- Sustainable Food Systems: The "Three Sisters" and other polyculture techniques offer models for resilient, nutritious, and environmentally friendly food production.

- Water Conservation: Ancient irrigation techniques and river management strategies provide valuable lessons for regions facing water scarcity.

- Ecosystem Restoration: Indigenous-led restoration efforts are proving highly effective in healing damaged landscapes.

For the traveler and history enthusiast, understanding this "map" transforms a landscape from a mere scenic vista into a living testament to human ingenuity, resilience, and profound connection. When you visit a national park, drive through a forest, or walk along a river, consider that the "wildness" you perceive may have been meticulously managed for thousands of years by the original inhabitants. Learning about and supporting these ongoing efforts of Indigenous resource management is not just about historical education; it’s about investing in a more sustainable future for all. It’s an invitation to shift our perspective from viewing nature as something to conquer to something to cherish, learn from, and ultimately, be a part of.