Beyond the Lines: Navigating the Living Map of Maliseet Nation Traditional Lands in Maine

Forget the neatly drawn lines of modern state boundaries. To truly understand the Maliseet Nation, or Wolastoqiyik as they call themselves – the People of the Beautiful River – one must look beyond contemporary maps and embrace a living, breathing landscape shaped by millennia of intimate connection, profound history, and enduring identity. This article delves into the traditional lands of the Maliseet Nation within what is now Maine, offering a historical and cultural lens suitable for the discerning traveler and history enthusiast.

The Wolastoq: The Artery of a Nation

At the heart of the Maliseet traditional territory is the Wolastoq, known today as the St. John River. This isn’t merely a geographical feature; it is the very pulse of their existence, the arterial highway that shaped their movements, sustained their communities, and gave them their name. Originating in the highlands of northwestern Maine, the Wolastoq flows majestically southeastward, through New Brunswick, before emptying into the Bay of Fundy. For the Maliseet, the river and its vast watershed – encompassing numerous tributaries, lakes, and forests within Maine – was their traditional homeland, a comprehensive and interconnected ecosystem.

A Maliseet "map" was not a static document but a mnemonic tapestry woven from generations of oral history, place names, seasonal migration routes, and a deep understanding of the land’s bounty. It included every bend in the river, every fishing weir, every hunting ground, every sacred site. This intimate knowledge ensured sustainable living and a harmonious relationship with their environment.

Defining Traditional Maliseet Territory in Maine

While the Wolastoq is central, the traditional Maliseet lands extended far beyond its immediate banks. In what is now Maine, their territory encompassed vast swathes of the northern and eastern regions. This included:

- The Headwaters of the Wolastoq: The northwestern reaches of Maine, particularly areas around the present-day Aroostook County, were critical headwaters, providing access to diverse ecosystems and strategic vantage points.

- The Aroostook River Valley: A significant tributary of the Wolastoq, the Aroostook River and its surrounding valley were integral Maliseet lands, rich in fish, game, and fertile ground. Its network of streams and lakes formed a vital inland transportation route.

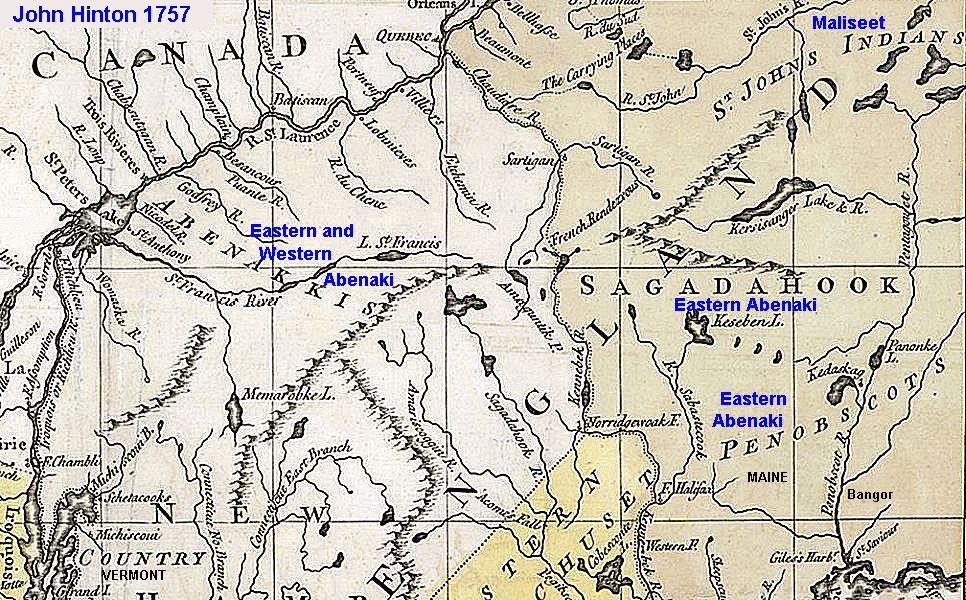

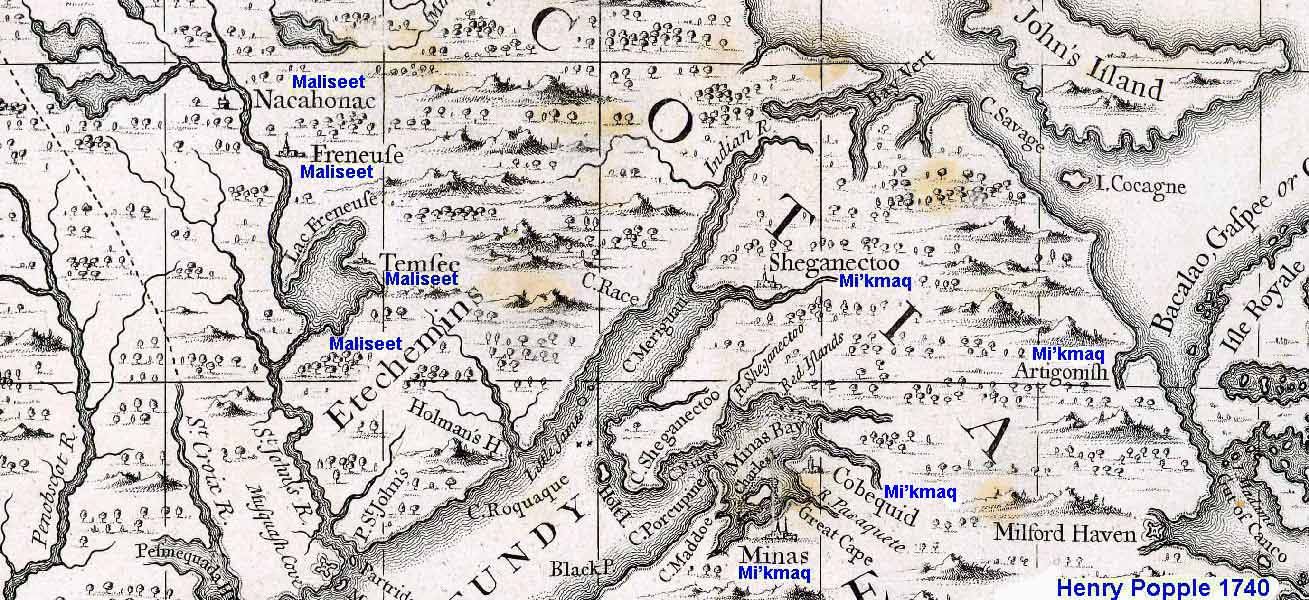

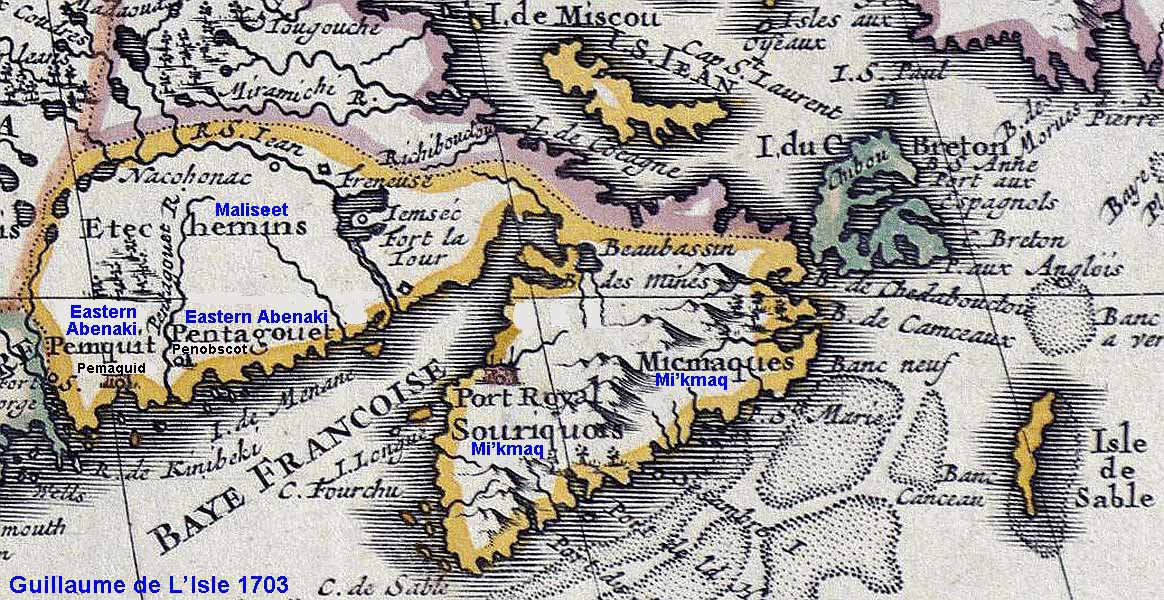

- Shared and Overlapping Territories: Like all Indigenous nations, the Maliseet did not live in isolation. Their traditional lands in Maine often overlapped and were shared with other members of the Wabanaki Confederacy, particularly the Penobscot and Passamaquoddy, and sometimes the Abenaki. These shared territories were managed through complex systems of alliances, diplomacy, and resource-sharing protocols, emphasizing cooperation rather than rigid, exclusive boundaries. The headwaters of the Penobscot River, for instance, saw Maliseet presence and use.

- The Appalachians to the Atlantic: Their influence and seasonal movements could extend from the Appalachian foothills in western Maine, across the vast forested interior, and down towards coastal areas for specific resources, though their primary focus remained the river system.

This traditional map was not defined by surveyor’s lines, but by ecological understanding and cultural memory – a dynamic representation of where the people lived, hunted, fished, gathered, traveled, and buried their ancestors.

A Tapestry of History: From Ancient Roots to Colonial Overwrite

The history of the Maliseet Nation on these lands stretches back thousands of years, far predating European arrival.

Pre-Contact Flourishing: For millennia, the Maliseet were master canoe builders and navigators, utilizing the extensive river systems as their highways. They were skilled hunters of moose, deer, and bear, expert fishers of salmon, sturgeon, and eels, and meticulous gatherers of wild plants, berries, and medicinal herbs. Their society was sophisticated, with a rich oral tradition, complex spiritual beliefs, and a deep reverence for the natural world. They were an integral part of the Wabanaki Confederacy – a political and military alliance with the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, and Abenaki – formed to protect their collective territories and ways of life.

The Onset of European Contact: The arrival of Europeans in the 16th and 17th centuries marked a profound turning point. Initially, contact brought new trade goods, but it quickly escalated into an era of devastating epidemics, land encroachment, and fierce geopolitical struggles between competing colonial powers – France and Britain. The Maliseet, strategically located between these empires, found themselves caught in a series of conflicts. They often allied with the French, who generally maintained more respectful trading relationships and less aggressive land claims compared to the British.

The Legacy of War and Displacement: The centuries of colonial wars (King William’s War, Queen Anne’s War, Father Rale’s War, King George’s War, and the French and Indian War) were catastrophic. Maliseet warriors fought valiantly to protect their homelands, but their populations were decimated by disease and warfare. The eventual British victory meant the imposition of foreign laws and land concepts that were alien to Indigenous understandings. The idea of "terra nullius" (empty land) or land as a commodity to be bought and sold was a stark contrast to the Maliseet’s communal stewardship.

Treaties and Their Absence in Maine: Unlike some other Indigenous nations in Canada, the Maliseet in Maine largely lacked formal, comprehensive treaties with the United States government that clearly defined and protected their land rights. This absence proved devastating. As settlers pushed northward and eastward into Maine, Maliseet lands were progressively absorbed, surveyed, and sold off without consent or compensation. The few "agreements" made were often manipulative, lacking true informed consent, and quickly disregarded.

The Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act of 1980: It wasn’t until the late 20th century that some redress began. The Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act of 1980 was a landmark agreement that partially resolved land claims for the Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, and the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians (the federally recognized Maliseet tribe in Maine). While it provided federal recognition, limited land acquisitions (approximately 5,000 acres for the Houlton Band), and financial compensation, it also imposed significant limitations on tribal sovereignty, particularly concerning regulatory authority over their lands. It was a compromise born of necessity, not a full restoration of their vast traditional territory.

Identity Woven into the Land

For the Maliseet, identity is inextricably linked to the land and the Wolastoq. This connection transcends mere ownership; it is a spiritual, cultural, and linguistic bond.

- Wolastoqey Language: The Maliseet language (Wolastoqey) is rich with place names and descriptive terms that reflect their intimate knowledge of the environment. Every hill, stream, and significant tree once had a Maliseet name, embodying stories, historical events, and practical knowledge. The revitalization of the language is a critical aspect of reclaiming and asserting identity.

- Oral Traditions and Stories: The Maliseet’s history, values, and understanding of the world are preserved through a vibrant oral tradition. These stories often feature the landscape as a character, teaching lessons about respect for nature, community responsibility, and the enduring spirit of the people.

- Stewardship and Sustainability: The Maliseet worldview emphasizes guardianship of the land for future generations. This traditional ecological knowledge is increasingly recognized as vital for addressing contemporary environmental challenges, from climate change to biodiversity loss. Their fight for sovereignty often includes advocating for environmental protection and sustainable resource management within their ancestral lands.

- Resilience and Self-Determination: Despite centuries of dispossession and cultural suppression, the Maliseet have maintained their identity and continue to assert their rights. The Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians, based near Houlton, Maine, is a testament to this resilience. They operate their own tribal government, pursue economic development, and work tirelessly to preserve their language, culture, and traditional practices, ensuring the Wolastoqiyik future.

Engaging with Maliseet Heritage: A Call for Respectful Exploration

For travelers and history buffs venturing into Maine, particularly its northern and eastern reaches, understanding the Maliseet Nation’s history and traditional lands offers a profound layer of appreciation.

- Acknowledge the Original Stewards: Before you explore a pristine lake, hike a remote trail, or paddle a river in Maine, take a moment to acknowledge that you are on the ancestral lands of the Maliseet and other Wabanaki people. This simple act of recognition shifts perspective.

- Learn Beyond the Textbooks: Seek out resources from the Maliseet Nation themselves. While direct public access to tribal lands might be limited or require permission, learning from their perspectives through websites, cultural centers, and official statements is invaluable.

- Support Indigenous Initiatives: If opportunities arise to support Maliseet artists, cultural events, or businesses, do so respectfully. This contributes directly to tribal self-sufficiency and cultural preservation.

- Understand Sovereignty: Recognize that the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians is a sovereign nation within the borders of Maine and the United States. This means they have inherent rights to self-governance and to manage their own affairs.

- Respect the Landscape: When you are in nature, remember the deep spiritual and historical significance it holds for the Maliseet. Practice Leave No Trace principles, respect wildlife, and tread lightly, understanding that every part of this landscape tells a story.

Conclusion

The traditional Maliseet Nation map in Maine is not merely a historical artifact; it is a living narrative. It speaks of a profound bond between a people and their homeland, a story of ancient wisdom, devastating loss, and remarkable resilience. By understanding this deeper map – one woven from the waters of the Wolastoq, the contours of the land, and the enduring spirit of the Wolastoqiyik people – we gain not only historical insight but also a richer, more respectful appreciation for the vibrant Indigenous heritage that continues to shape the character of Maine. To truly see Maine is to see it through the eyes of its first peoples, and to honor the enduring presence of the Maliseet Nation.