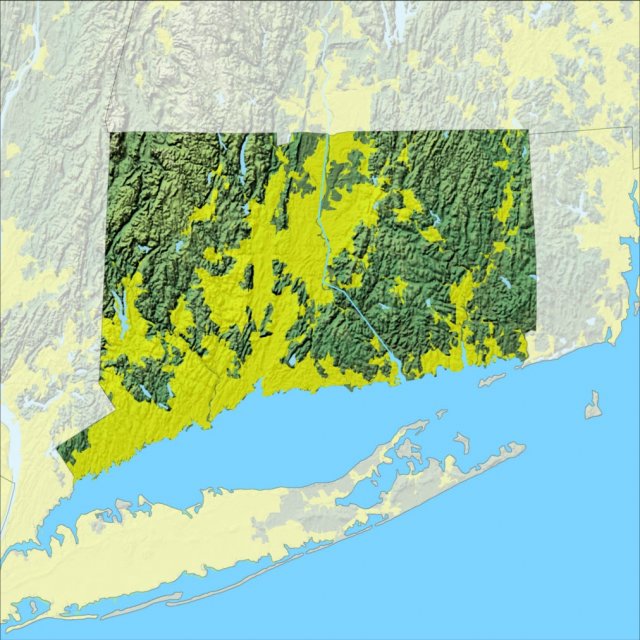

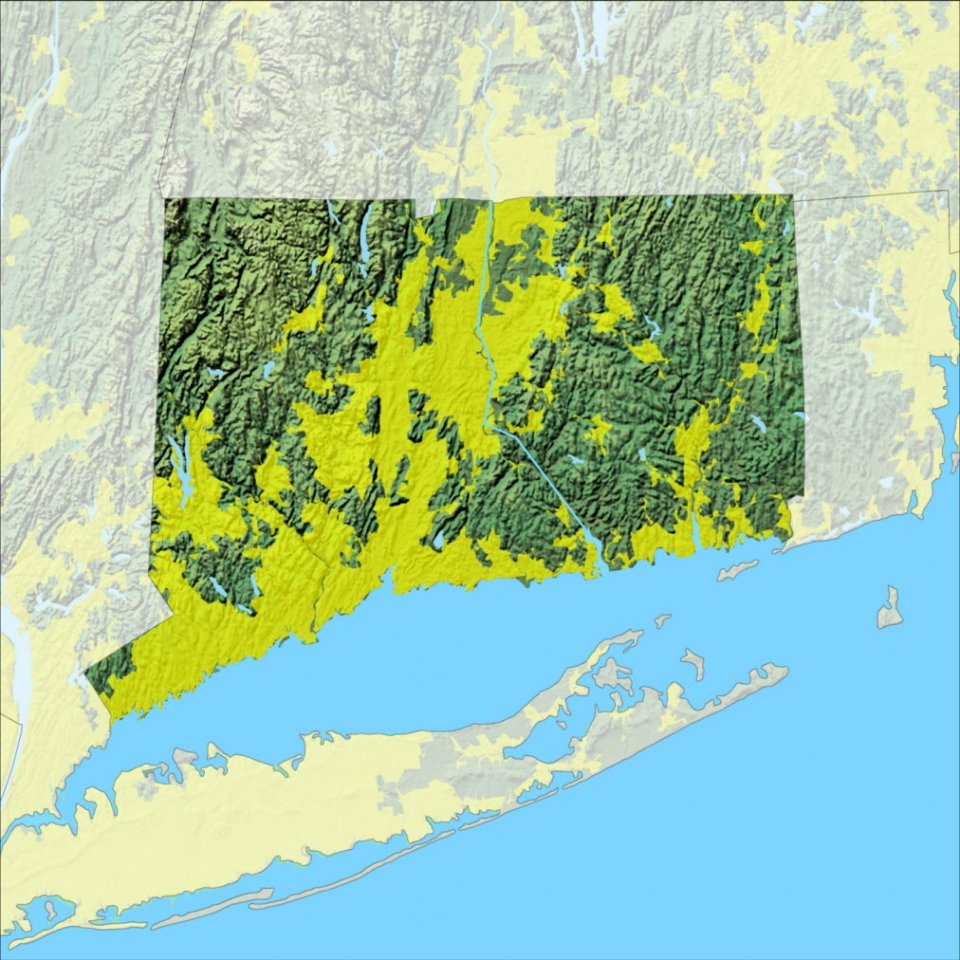

The land speaks. For the Mohegan Tribe, the traditional lands map of Connecticut is not merely a static document outlining historical boundaries; it is a living testament to an enduring presence, a narrative woven into the very fabric of the landscape, and a profound declaration of identity. This article delves into the rich history and deep cultural significance embedded within the Mohegan ancestral territory, offering a perspective crucial for both the curious traveler and the history enthusiast.

The Mohegan Homeland: A Tapestry of Land and Spirit

To understand the Mohegan map is to understand the Mohegan people. The name "Mohegan" itself, derived from "Ma’iingan" (meaning "wolf"), speaks to their deep connection with the natural world and their identity as "Wolf People." Historically, the Mohegan were an Algonquian-speaking people whose traditional lands encompassed a significant portion of southeastern Connecticut, primarily centered around the Thames River watershed, which they knew as the "Mohegan River."

Before European contact, the Mohegan territory was a dynamic landscape of forests, rivers, wetlands, and coastal areas, providing abundant resources for hunting, fishing, gathering, and agriculture. Their villages were typically situated along waterways, facilitating travel and access to food. The Mohegan lived in harmony with the seasons, moving between summer encampments for planting and fishing and winter sites for hunting and shelter. Their societal structure was organized, with a sachem (chief) leading the community, advised by a council of elders. Spiritual beliefs were intrinsically linked to the land, recognizing the sacredness of specific sites, the spirits within nature, and the interconnectedness of all living things.

The "map" of this traditional land was not a parchment scroll with delineated lines but a mental construct, passed down through generations, understood through stories, songs, and intimate knowledge of every stream, hill, and forest path. It was a territory defined by relationships—relationships with neighboring tribes, with the spirits of the land, and with the resources that sustained them. Key geographical features like Fort Shantok, a naturally fortified peninsula overlooking the Thames River, served not only as a strategic stronghold but also as a sacred burial ground and a central gathering place, solidifying its place as the heart of Mohegan identity. Mohegan Hill, another prominent feature, held similar spiritual and cultural significance, representing a place of origin and continuity.

The Crucible of Contact: Uncas, Alliances, and the Pequot War

The 17th century brought monumental shifts to the Mohegan world with the arrival of European colonists—first the Dutch, then the English. This period marks the beginning of documented, albeit often biased, mapping efforts and the imposition of European concepts of land ownership.

A pivotal moment in Mohegan history, and indeed in the history of Connecticut, was the split from the larger Pequot Confederacy. Under the leadership of Sachem Uncas, the Mohegan asserted their distinct identity and independence from the dominant Pequot. This separation, fueled by internal rivalries and political dynamics, occurred just as European powers were vying for control of the region.

Uncas, a brilliant and often controversial strategist, recognized the shifting power dynamics. Rather than confronting the technologically superior English, he forged a crucial alliance with them. This alliance was put to its ultimate test during the Pequot War of 1637. The Mohegan, alongside the Narragansett and the English, launched a devastating attack on the main Pequot fort at Mystic. The war resulted in the near annihilation of the Pequot as a unified political entity and fundamentally reshaped the indigenous landscape of southern New England.

For the Mohegan, the alliance with the English, while ensuring their survival and enhancing their status among the remaining tribes, came at a profound cost. It entangled them in colonial politics, led to escalating land cessions, and ultimately set the stage for centuries of struggle to maintain their sovereignty and ancestral lands. The traditional Mohegan map, once an expansive domain, began to shrink under the pressure of colonial expansion, marked by treaties and deeds that often exploited linguistic and cultural misunderstandings.

The Long Struggle: Land Loss, Resilience, and Cultural Preservation

The post-Pequot War era saw the Mohegan, under Uncas and his successors, navigate a treacherous political landscape. While they were recognized by the English as an independent tribe and granted a reservation in their traditional territory (initially 4,000 acres around Fort Shantok), the pressure to cede land was relentless. English settlements like Norwich and New London rapidly expanded, encroaching upon Mohegan hunting grounds and agricultural lands.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the Mohegan engaged in a series of protracted legal battles, famously known as the Mason Land Cases, to defend their reservation from illegal encroachment by English settlers. These cases, though ultimately unsuccessful in recovering much of the lost land, demonstrated the Mohegan’s unwavering commitment to their territory and their sophisticated understanding of colonial legal systems. It was a testament to their resilience and their refusal to vanish.

Despite the immense pressures of assimilation, disease, and economic hardship, the Mohegan found ways to preserve their culture and identity. While English became the dominant language, elders continued to pass down stories, traditions, and knowledge of the land. The establishment of the Mohegan Church in the 1830s, founded by tribal members, became a crucial center for community life, blending Christian worship with Mohegan cultural practices and providing a space for solidarity and self-determination.

Key figures emerged during this period who embodied the Mohegan spirit of survival. Samson Occom (1723-1792), a Mohegan minister and educator, became one of the first Native Americans to publish works in English. He tirelessly advocated for his people and other Native communities, traveling to England to raise funds for what would become Dartmouth College, though the college ultimately failed to fulfill its original mission to educate Native Americans. His efforts highlighted the intellectual prowess and moral clarity of Mohegan leaders. Later, in the 20th century, Fidelia Hoscott Fielding (1820-1908) became the last fluent speaker of the Mohegan-Pequot language, diligently documenting her knowledge in journals, a priceless gift that would later aid in the language’s revitalization. These individuals represent the unbroken chain of Mohegan identity, connecting the ancient past to the contemporary present.

Reclaiming Sovereignty: The Fight for Federal Recognition

The 20th century witnessed a renewed determination within the Mohegan community to reclaim their sovereignty and assert their rightful place. The map of their traditional lands, by then largely in non-Native hands, became a powerful symbol of what was lost and what needed to be reclaimed, not necessarily in physical acreage, but in recognition and respect.

The most significant chapter in this modern struggle was the decades-long pursuit of federal recognition. The Mohegan Tribe, like many other Native American nations, had been "terminated" or simply never formally recognized by the U.S. government, denying them the rights and protections afforded to federally recognized tribes. This meant a constant battle against the erosion of their identity and the inability to fully exercise self-governance.

Through meticulous historical research, oral testimonies, and unwavering political advocacy, the Mohegan Tribe painstakingly documented their continuous existence as a distinct political and cultural entity since time immemorial. Their efforts culminated in 1994, when the Mohegan Tribe officially received federal recognition, a landmark achievement that restored their inherent sovereignty. This recognition was not merely a bureaucratic formality; it was a profound act of justice, validating centuries of Mohegan resilience and affirming their right to self-determination.

The Map Today: A Living Legacy and Future Vision

With federal recognition came the ability to establish a land trust and to begin rebuilding their nation. This is where the modern manifestation of the Mohegan traditional lands map truly comes alive. The Mohegan Reservation, established on a small fraction of their ancestral lands in Montville, Connecticut, became the sovereign territory from which the tribe could launch its future.

A cornerstone of this revitalization was economic development. The Mohegan Tribe strategically entered the gaming industry, opening Mohegan Sun in 1996. This enterprise, one of the largest and most successful casino resorts in the world, is far more than just a business; it is the economic engine that funds tribal government, healthcare, education, cultural preservation, and land acquisition. It is a modern expression of sovereignty, enabling the tribe to self-sufficiency and to serve its people.

The Mohegan traditional lands map, therefore, is not just a historical relic. It serves multiple, vital functions today:

- Cultural Anchor: It reinforces the deep spiritual and cultural connection to the land, reminding Mohegan people of their ancestral roots and responsibilities to steward the environment. Cultural preservation programs, language revitalization efforts (using Fidelia Fielding’s journals), and traditional ceremonies are all rooted in this understanding of place.

- Educational Tool: For both tribal members and the wider public, the map is a powerful educational resource. It teaches younger generations about their heritage, while informing non-Natives about the true history of Connecticut and the enduring presence of Indigenous peoples.

- Sovereignty Statement: It visually represents the Mohegan’s inherent right to self-governance and their unbroken chain of nationhood, regardless of colonial boundaries.

- Environmental Stewardship: The Mohegan Tribe continues to be deeply committed to environmental protection and sustainable practices within their traditional territory, reflecting their ancient understanding of reciprocal relationship with Mother Earth. This includes efforts to restore waterways, protect forests, and preserve biodiversity.

- Future Vision: The map inspires future generations to continue the work of their ancestors—to thrive, to preserve their culture, and to ensure the well-being of their people.

Conclusion: Beyond Borders, an Enduring Identity

The Mohegan Tribe’s traditional lands map of Connecticut is more than a geographical representation; it is a narrative of profound resilience, strategic adaptation, and unwavering identity. It tells a story of an ancient people who have navigated centuries of change, conflict, and challenge, yet remain vibrantly present and self-determined.

For the traveler seeking to understand Connecticut’s deep history, or the student exploring Native American studies, the Mohegan map offers an indispensable lens. It reminds us that history is not static, that sovereignty is not merely a legal term, and that the connection between a people and their land is an eternal bond. The Mohegan people, the "Wolf People," continue to walk their ancestral lands, honoring their past, shaping their present, and forging a powerful future, their story forever etched into the landscape of Connecticut. To truly see this map is to recognize a living, breathing nation, whose journey continues to inspire and educate.