The Enduring Heartbeat of the Land: A Journey Through Potawatomi Nation Historical Territories

To truly understand the landscape of the Great Lakes region and beyond, one must look beyond modern political boundaries and delve into the historical territories of its original peoples. The Potawatomi Nation, known as Neshnabé or Neshnabemwin speakers, are a vital thread in the intricate tapestry of North American history. Their ancestral lands, spanning a vast expanse, tell a compelling story of identity, resilience, and profound connection to the earth. This exploration of the Potawatomi historical lands map is not merely a geographical exercise; it is an invitation to understand a people whose spirit remains intrinsically linked to the waterways, forests, and prairies they once called home.

The Potawatomi, meaning "Keepers of the Fire," are one of the three nations of the Council of Three Fires (Niswi-mishkodewin), an enduring Anishinaabe alliance alongside the Ojibwe (Chippewa) and Odawa (Ottawa). Their origin stories speak of a migration from the eastern seaboard, eventually settling in the rich ecological zones around the Great Lakes. Initially, their core territory encompassed a significant portion of what is now Michigan’s Lower Peninsula, stretching south into northern Indiana and Ohio, and west into parts of Wisconsin and Illinois. This was a land defined by its abundance: the vast freshwater seas of Lake Michigan, Lake Huron, and Lake Erie, the intricate network of rivers like the St. Joseph, Kalamazoo, and Maumee, and the sprawling deciduous forests teeming with game.

This vast homeland shaped Potawatomi identity. Their lifestyle was semi-nomadic, adapting to the seasonal rhythms of the land. Spring brought maple sugaring, fishing, and planting of corn, beans, and squash. Summer saw them tending gardens, gathering berries and medicinal plants, and engaging in communal activities. Fall was dedicated to hunting deer, elk, and waterfowl, harvesting wild rice, and preparing for winter, when families would disperse to smaller hunting camps. Their sophisticated understanding of the environment allowed them to thrive, living in harmony with its resources. Villages were organized around extended families and clans, each with specific responsibilities and spiritual totems. Leadership was often consensual, based on wisdom, experience, and oratorical skill. Their spiritual beliefs were deeply animistic, recognizing the spirit in all living things and the profound interconnectedness of the natural world, guided by the Great Spirit (Gitchi Manidoo).

The Potawatomi’s strategic location at the nexus of major trade routes, particularly the waterways connecting the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River basin, made them crucial intermediaries in the early contact period with Europeans. French fur traders were among the first to establish relationships, recognizing the Potawatomi’s skill as hunters and traders. This initial contact, while introducing new goods like metal tools and firearms, also brought disruptive forces: disease, alcohol, and the increasing pressures of European colonial competition. The Potawatomi skillfully navigated these complex alliances, often playing French against British, and later British against Americans, always striving to protect their sovereignty and ancestral lands. They were formidable warriors, participating in conflicts like Pontiac’s War and the American Revolution, often aligning with those who offered the best chance of resisting encroachment.

However, the tide began to turn dramatically after the American Revolution. The newly formed United States viewed the fertile lands of the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes as essential for westward expansion. This ushered in the era of treaties – a period of systematic land cession that irrevocably altered the Potawatomi historical map. From the late 18th century through the mid-19th century, the Potawatomi Nation was subjected to a relentless series of treaties, many signed under duress, coercion, or through the manipulation of internal factions. Treaties like the Treaty of Greenville (1795), the Treaty of Fort Wayne (1809), and especially the Treaty of Chicago (1821 and 1833) saw vast tracts of ancestral land, sometimes millions of acres at a time, relinquished for meager compensation or promises that were often broken.

The Treaty of Chicago in 1833, in particular, marked a devastating turning point. It was signed amidst immense pressure and internal divisions, ceding the last remaining Potawatomi lands in Illinois and much of their remaining territory in Michigan and Wisconsin. This treaty effectively fractured the Nation, setting the stage for forced removals. The United States government’s policy, solidified by the Indian Removal Act of 1830, aimed to relocate all Native American tribes west of the Mississippi River. For the Potawatomi, this policy manifested in the tragic "Trail of Death."

In 1838, over 850 Potawatomi, primarily from Indiana, were forcibly removed from their homes and marched at gunpoint across Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, and Kansas. The journey, lasting 61 days, was rife with suffering. Lack of food, water, and sanitation, coupled with disease, claimed the lives of over 40 people, mostly children and the elderly. This traumatic event is a stark reminder of the human cost of westward expansion and the brutal realities of Manifest Destiny. It resulted in the scattering of the Potawatomi people, creating distinct bands and communities in places far removed from their original Great Lakes homeland.

Despite these immense challenges – the loss of land, the trauma of removal, the attempts at cultural suppression through boarding schools and assimilation policies – the Potawatomi people demonstrated extraordinary resilience. They rebuilt their communities, often from scratch, in new territories. Today, the Potawatomi Nation is not a single, unified entity in one geographical location, but rather a collection of federally recognized and unceded bands and nations spread across the United States and Canada.

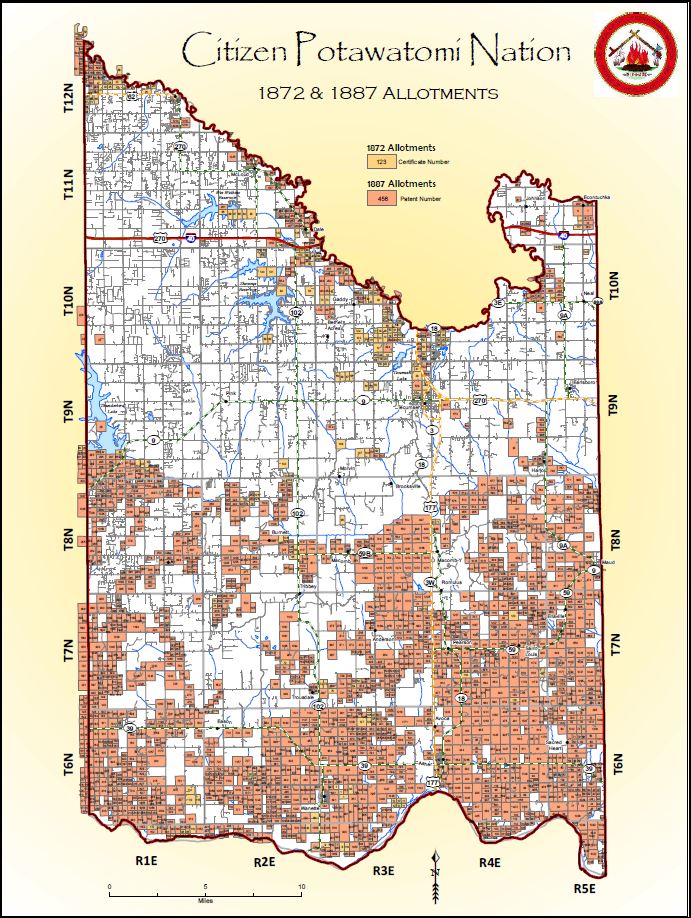

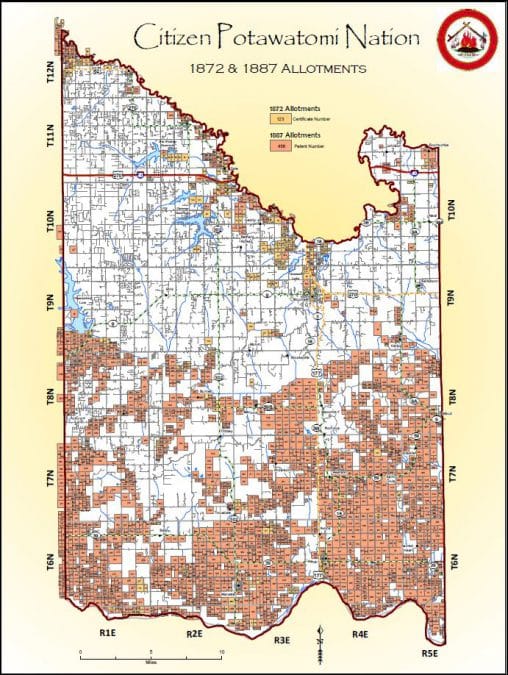

In the U.S., major Potawatomi nations include the Citizen Potawatomi Nation (Oklahoma), the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation (Kansas), the Forest County Potawatomi Community (Wisconsin), the Hannahville Indian Community (Michigan), the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi (Michigan), and the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians (Michigan/Indiana). Each of these nations, while sharing a common heritage and language (Neshnabemwin), has its own distinct history of removal, adaptation, and resurgence. In Canada, Potawatomi communities are part of the Anishinabek Nation, particularly in southern Ontario.

These contemporary nations are vibrant, self-governing entities. They are actively engaged in preserving and revitalizing their language, traditions, and ceremonies. Cultural centers, museums, and educational programs are vital in transmitting knowledge to younger generations. Economic development initiatives, ranging from gaming and tourism to sustainable agriculture and renewable energy, are empowering these nations and contributing to the well-being of their citizens. The connection to the land, though geographically dispersed, remains a powerful force, expressed through stewardship, traditional practices, and a deep historical memory.

For the traveler and history educator, understanding the Potawatomi historical lands map offers profound insights. When you stand on the shores of Lake Michigan, traverse the forests of Indiana, or drive through the prairies of Kansas, you are on land with a rich and complex human story that predates colonial narratives. The rivers flow with the echoes of their canoes, the forests whisper tales of their hunters, and the earth holds the memory of their villages and sacred sites.

Visiting the cultural centers and museums of modern Potawatomi nations, where respectful engagement is encouraged, provides an invaluable opportunity to learn directly from the descendants of these lands. It is a chance to move beyond abstract maps and connect with the living history of a people who have endured, adapted, and continue to thrive. This journey through Potawatomi historical territories is not just about tracing lines on an old map; it is about recognizing the enduring spirit of a Nation, whose past shapes our present and informs our future understanding of this diverse and storied continent. The "Keepers of the Fire" continue to tend their flame, illuminating a path of resilience, identity, and an unwavering connection to their ancestral lands, no matter where they may reside today.