The Unseen Threads of the Land: Decoding the Taos Pueblo Traditional Lands Map

The Taos Pueblo traditional lands map is not a mere cartographic rendering of boundaries; it is a profound historical document, a spiritual testament, and a living chronicle of identity. For the people of Taos Pueblo, the land is not property to be owned but a sacred entity that embodies their history, sustains their culture, and defines their very being. To understand this map is to embark on a journey through centuries of resilience, spiritual connection, and an enduring struggle for sovereignty.

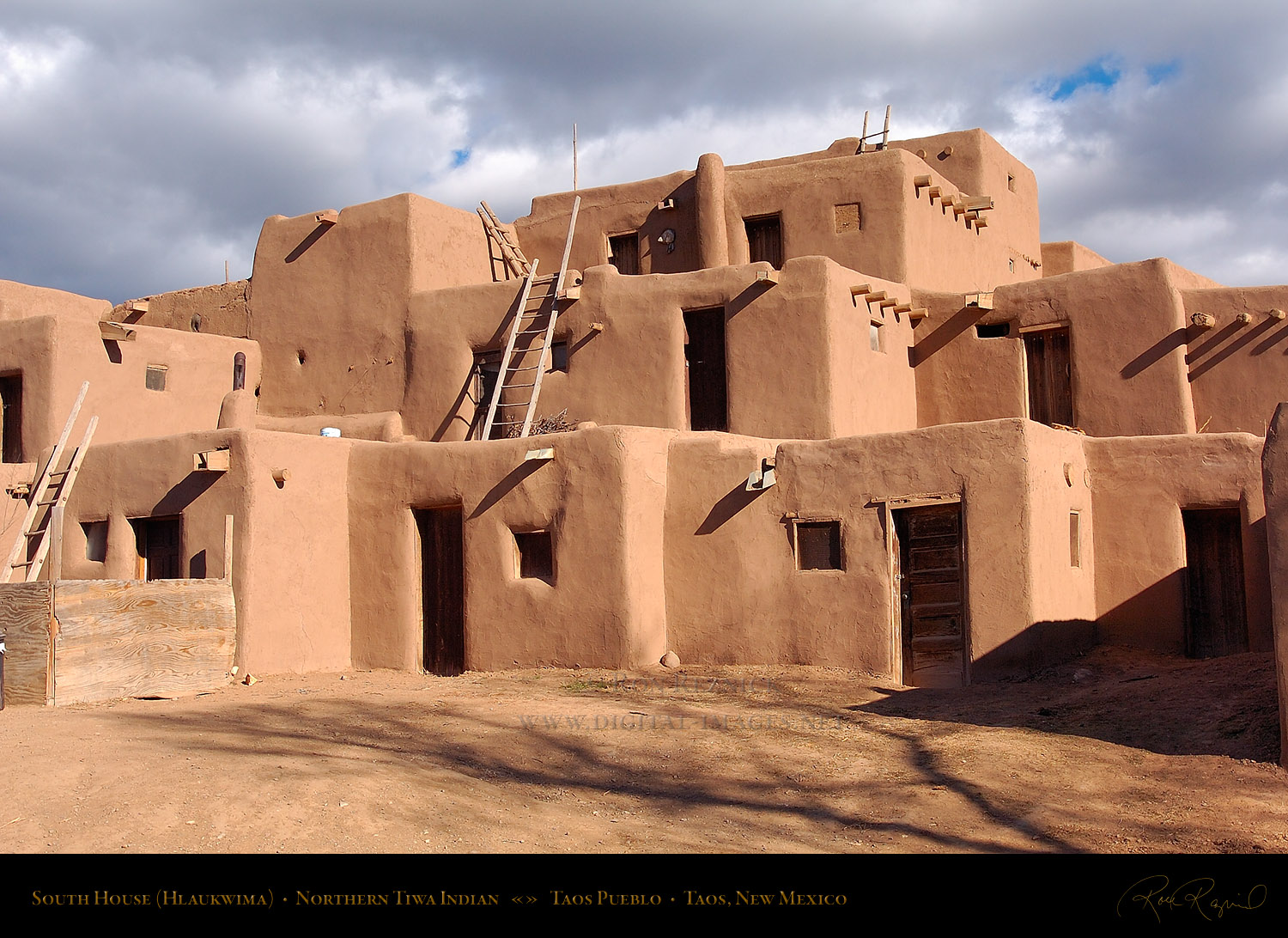

Directly nestled at the foot of the majestic Sangre de Cristo Mountains in northern New Mexico, Taos Pueblo represents the oldest continuously inhabited community in North America, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that predates European arrival by over a millennium. Its iconic multi-storied adobe dwellings, bisected by the sacred Rio Pueblo de Taos, stand as a physical manifestation of a profound and unbroken connection to the earth. The traditional lands map extends far beyond the visible pueblo structures, encompassing a vast and intricate network of mountains, forests, rivers, and plains that have nurtured the Tiwa-speaking people for countless generations.

The Land Before Lines: Pre-Colonial Landscape and Identity

Before the advent of European cartography and the concept of fixed, surveyed property lines, the Taos people held a sophisticated and intimate understanding of their ancestral domain. Their "map" was etched into their collective memory, passed down through oral traditions, ceremonies, and daily practices. It encompassed hunting grounds stretching into the high mountains, gathering areas for medicinal plants and edible wild foods, sacred sites for spiritual renewal and ceremonies, and agricultural fields along the river valleys.

This was a dynamic landscape, not static. The Taos people lived in a symbiotic relationship with their environment, understanding the migratory patterns of game, the seasonal cycles of plants, and the sacred power of specific springs and peaks. The mountains, particularly Taos Mountain (Taa-E-Weh-Pah-Towa), were not just a backdrop but a central spiritual figure, a provider, and a protector. The Rio Pueblo de Taos, flowing directly through the heart of the pueblo, was and remains the lifeblood, its waters essential for drinking, agriculture, and ceremonial purification. Their identity was entirely interwoven with these specific geographical features; they were the people of this land.

The Imposition of New Maps: Spanish, Mexican, and American Eras

The arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century marked the beginning of a profound disruption to this ancient relationship. With the Spanish came new concepts of land ownership – encomiendas, land grants, and the imposition of a colonial administrative system. While the Pueblo people resisted fiercely, most notably in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, Spanish claims to vast territories inevitably impacted Taos’s traditional lands. Grants were made to Spanish settlers, often overlapping with or encroaching upon areas the Taos people considered their own for hunting, grazing, and resource gathering. The Taos Pueblo, however, maintained a relatively strong hold on their core village lands, a testament to their resilience and strategic importance.

Following Mexican independence in 1821, the landscape of land claims continued to shift, though the pressure on native lands persisted. It was the American annexation of New Mexico after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 that introduced the most drastic and enduring changes. The American system of land management, based on rectangular surveys, homesteading, and the creation of "public lands" (national forests, national parks), systematically dispossessed Indigenous peoples of vast tracts of their ancestral territories.

For Taos Pueblo, this meant the gradual erosion of their traditional use areas. Lands that had been integral for hunting, gathering, and spiritual ceremonies for millennia were suddenly declared federal property, often designated as national forests. This legal reclassification stripped the Taos people of their inherent rights to these lands, even though their cultural and spiritual connection remained unbroken and their traditional practices continued, albeit under threat.

Unpacking the Traditional Lands Map: More Than Just Lines

When we speak of the "Taos Pueblo traditional lands map" today, we are often referring to a document or concept that attempts to articulate and reclaim what was lost or threatened during these colonial periods. It’s not just about the relatively small land grant officially recognized by the Spanish and later the U.S. government as the Taos Pueblo Grant. It’s about the much larger area of use and spiritual significance that defines their ancestral domain.

.jpg)

This map, whether explicitly drawn or understood through cultural narratives, encompasses:

- The Core Pueblo Lands: The ancient village itself and its immediate agricultural fields, which have been continuously occupied and farmed.

- Hunting and Gathering Grounds: Extensive mountain ranges, valleys, and plains crucial for subsistence and traditional economic activities. These areas provided deer, elk, bear, various birds, as well as crucial plant resources like piñon nuts, berries, and medicinal herbs.

- Sacred Sites: Peaks, caves, springs, rock formations, and specific stretches of river that hold profound spiritual meaning, serving as places for ceremonies, pilgrimages, and vision quests. Taos Mountain itself is a paramount example, but countless other smaller, equally important sites dot the landscape.

- Ancestral Trails and Pathways: Networks that connected these various sites, facilitating trade, communication, and movement between seasonal camps.

- Water Sources: Rivers, streams, and springs vital for life, agriculture, and spiritual practices. The integrity of these water sources is inextricably linked to the health of the land and the people.

The map, therefore, is a layered document. It speaks of historical events, legal battles, spiritual journeys, and daily sustenance. It challenges the colonial gaze that sees "wilderness" where Indigenous peoples see a meticulously stewarded and deeply understood landscape.

The Fight for Blue Lake: A Landmark Victory

No discussion of the Taos Pueblo traditional lands map is complete without focusing on the monumental struggle for the return of Blue Lake (Ba-whyea-di). For the Taos people, Blue Lake, nestled high in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, is the most sacred of all their ancestral sites. It is considered the place of their emergence, the source of their life and spiritual strength, and the spiritual home of their ancestors. Its waters are central to their most sacred ceremonies, and its surrounding forests provide essential materials for religious rites.

In 1906, the U.S. government, under the guise of creating a national forest, unilaterally seized Blue Lake and its surrounding watershed, incorporating it into the Carson National Forest. This act was devastating to the Taos people. It denied them access to their holiest site, disrupted their religious practices, and threatened the very fabric of their cultural identity. Imagine a nation losing its holiest temple to a foreign government; this was the magnitude of the loss.

For over 60 years, the Taos Pueblo fought relentlessly for the return of Blue Lake. They petitioned Congress, engaged in legal battles, and educated the American public about the profound injustice. Their efforts culminated in 1970 when, after decades of advocacy and the support of President Richard Nixon, Congress passed legislation returning 48,000 acres of land, including Blue Lake, to the Taos Pueblo in trust. This was a landmark victory for Indigenous land rights in the United States, a powerful affirmation of spiritual connection over governmental claim, and a testament to the unwavering determination of the Taos people. The return of Blue Lake became a symbol of hope and justice for Native nations across the continent.

Identity Forged in Land: Modern Challenges and Enduring Spirit

The return of Blue Lake, while significant, did not end the Taos Pueblo’s efforts to protect and steward their traditional lands. Today, the "map" continues to inform their ongoing struggles and triumphs. They contend with complex water rights issues, crucial for maintaining their traditional agricultural practices and supporting the ecosystem. They engage in environmental stewardship, drawing upon millennia of ecological knowledge to manage their forests, prevent wildfires, and protect their water sources.

The traditional lands map also serves as a framework for managing tourism, a vital economic activity that must be carefully balanced with the preservation of their culture and sacred spaces. Visitors to Taos Pueblo are welcomed, but within strict guidelines designed to protect the privacy, sanctity, and traditional way of life of the residents. This respectful interaction underscores the idea that the land is not merely a scenic backdrop but a living, breathing part of their identity.

For the Taos people, their identity as Tiwa is inseparable from the land their ancestors walked, farmed, hunted, and prayed upon. The mountains, rivers, and forests are not just resources; they are kin, teachers, and a source of spiritual power. The map of their traditional lands is a testament to their continuous presence, their enduring culture, and their inherent sovereignty. It tells a story of survival, resistance, and a profound, unbreakable bond with the earth that transcends any lines drawn on paper by external powers.

Conclusion: A Living Map, A Living Culture

The Taos Pueblo traditional lands map, whether an explicit drawing or an implicit understanding, is a crucial lens through which to comprehend the rich history and vibrant identity of this ancient community. It is a powerful reminder that land is not just real estate, but the very foundation of culture, spirituality, and sovereignty for Indigenous peoples. To truly appreciate Taos Pueblo, one must look beyond the adobe walls and see the vast, interwoven landscape that has shaped its people for millennia. It is a map of resilience, a guide to a sacred past, and a blueprint for a future deeply rooted in tradition and respect for the earth. For the traveler and the student of history alike, understanding this map is to begin to grasp the enduring spirit of Taos Pueblo, a spirit as ancient and majestic as the mountains that embrace it.