Historical atlas maps of Native American nations are far more than static geographical representations; they are dynamic, layered narratives that encapsulate millennia of history, identity, sovereignty, and profound cultural connection to the land. For anyone interested in truly understanding the North American continent, its past, and its present, these maps offer an indispensable lens, revealing a complex tapestry often oversimplified or erased in conventional histories. Engaging with these atlases is not merely an academic exercise; it is a journey into the heart of Indigenous resilience and a crucial step towards informed travel and historical education.

The Pre-Colonial Tapestry: Dynamic Landscapes of Sovereignty

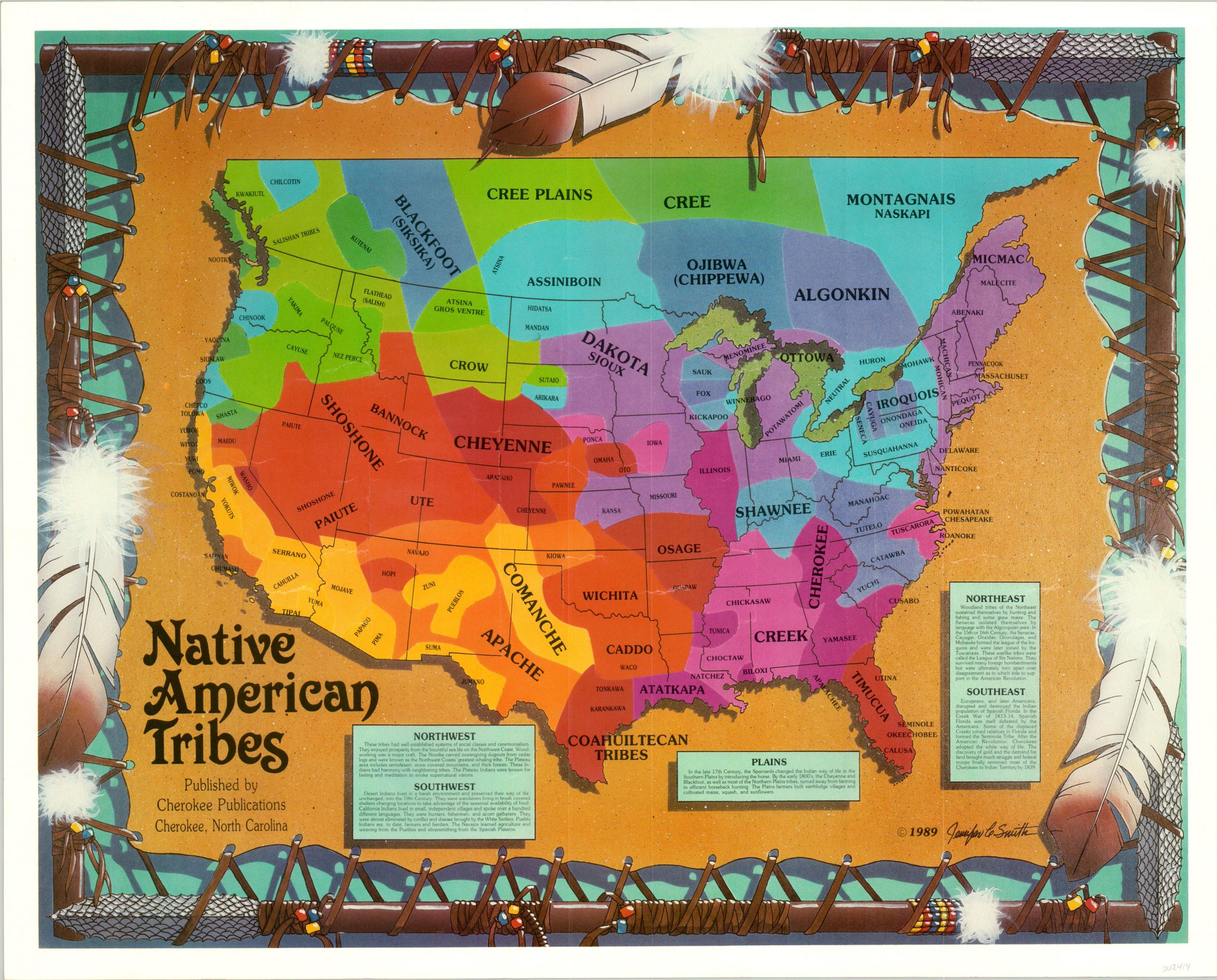

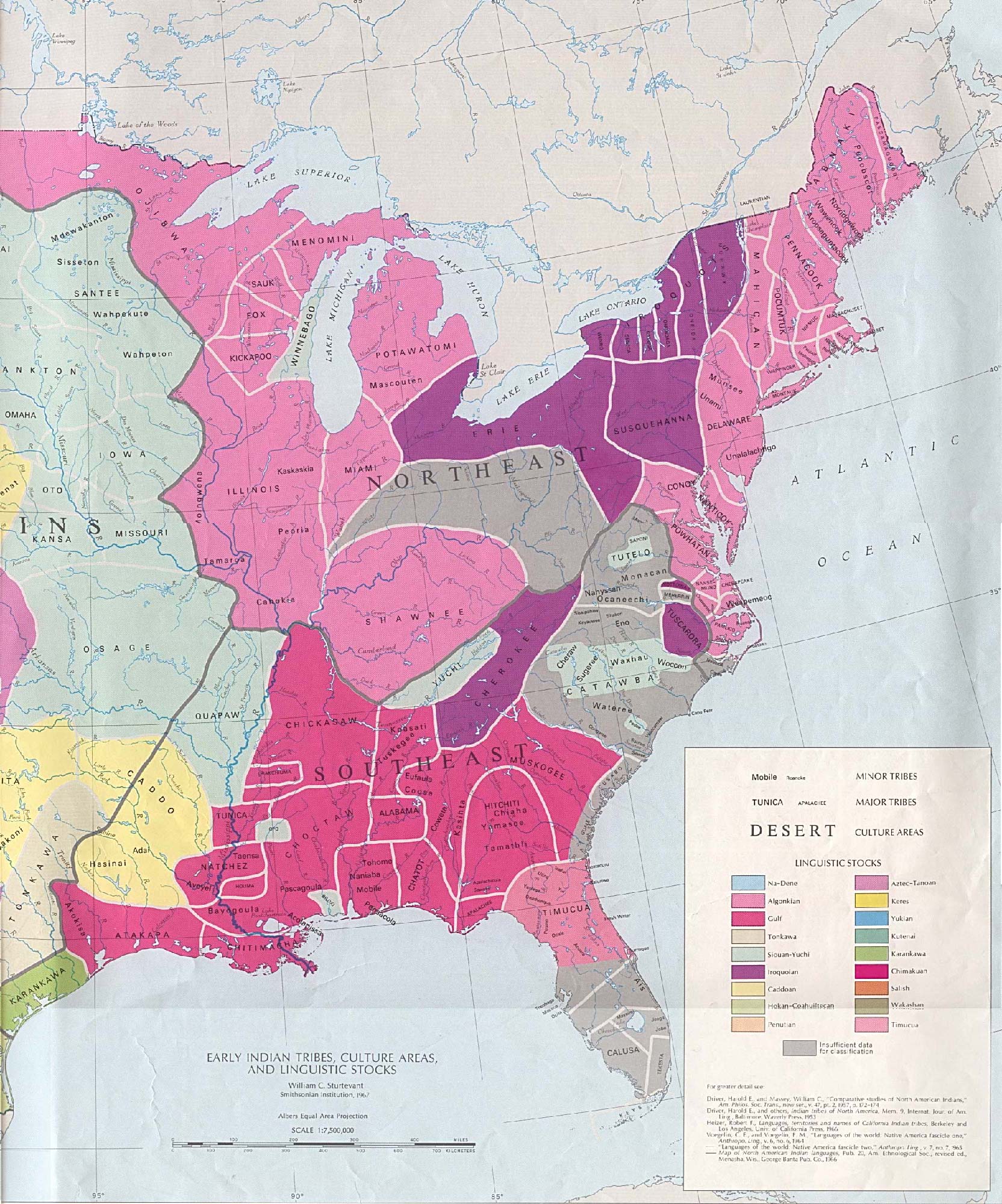

Before European contact, the land now known as the United States and Canada was a vibrant mosaic of hundreds of distinct Indigenous nations, each with its own language, governance, spiritual beliefs, and intricate relationship with its territory. Early historical atlas maps, even those attempting to depict pre-colonial boundaries, often struggle to capture the true fluidity and complexity of these arrangements. Unlike European concepts of fixed, impermeable borders, many Indigenous territories were defined by resource availability, seasonal movements, kinship ties, and shared usage rather than rigid lines.

These maps, even in their approximations, illustrate a continent teeming with diverse cultures. They show the vast territories of the Iroquois Confederacy, a powerful political and military alliance spanning parts of present-day New York and Canada; the expansive hunting grounds of the Plains nations like the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho; the agricultural lands and sophisticated urban centers of the Mississippian cultures in the Southeast; and the intricate trading networks of the Pueblo peoples in the Southwest. Each color, each shaded area, represents not just a location but a living, breathing society with its own system of law, economy, and spiritual connection to specific mountains, rivers, and forests.

Crucially, these pre-contact maps challenge the myth of "terra nullius" – the idea that the Americas were an empty, undeveloped wilderness awaiting European "discovery." They visually affirm that Indigenous peoples were not merely nomadic wanderers but sophisticated stewards of their environments, with established trade routes, complex diplomatic relations, and often dense populations. Understanding these early configurations is foundational to appreciating the scale of transformation that followed.

The Colonial Onslaught: Shifting Borders and Imposed Realities

The arrival of European powers irrevocably altered this Indigenous landscape, and subsequent maps become stark records of conquest, displacement, and the systematic erosion of Native sovereignty. Early colonial maps often depict vast, undifferentiated "Indian Country" alongside burgeoning European settlements, betraying a profound ignorance or deliberate dismissal of the existing Indigenous nations. As colonial expansion accelerated, these maps began to shift, reflecting a new, devastating reality.

Treaty maps, in particular, are powerful historical documents. Initially, many treaties were negotiated between sovereign nations, outlining land cessions, rights, and responsibilities. However, as European power grew, the nature of these treaties changed. Maps documenting treaty agreements often show Native territories shrinking dramatically with each subsequent negotiation, a visual testament to coercion, misunderstanding, and outright betrayal. The infamous "Trail of Tears" maps, depicting the forced removal of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole nations from their ancestral lands in the Southeast to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) in the 1830s, are particularly poignant examples. These lines on a map represent immense suffering, cultural destruction, and a profound rupture in Indigenous identity and connection to place.

The establishment of reservations, often far from ancestral homelands, is another critical chapter illuminated by these atlases. Reservation maps show the confinement of once expansive nations into circumscribed, often less desirable, parcels of land. These boundaries were drawn by external powers, often without consulting the Indigenous inhabitants, and frequently divided kin groups or forced disparate nations together. The "checkerboard" maps of reservation lands, showing parcels allotted to individual tribal members under the Dawes Act (1887) and subsequent policies, further illustrate the deliberate attempt to dismantle communal land ownership and integrate Native peoples into a Euro-American individualistic system. These maps are not just geographical; they are political manifestos of dispossession and cultural assimilation.

Identity and the Map: More Than Just Borders

For Native Americans, identity is inextricably linked to land. Historical atlas maps, therefore, are not just about where people lived, but about who they are. The names of rivers, mountains, and valleys in Indigenous languages often carry deep cultural, spiritual, and historical significance, reflecting stories, ceremonies, and traditional knowledge passed down through generations. When European cartographers renamed these features, it was not just a linguistic shift; it was an act of cultural erasure, severing a tangible link between people and their ancestral narratives.

However, these maps also serve as powerful reminders of the enduring presence and resilience of Native identity. Many contemporary maps produced by Indigenous communities or allied organizations reclaim original place names, asserting a continuous cultural presence despite centuries of colonial renaming. They show traditional ecological knowledge areas, language revitalization efforts, and sacred sites, reaffirming a profound and ongoing connection to specific landscapes. For example, a map showing the traditional hunting and gathering routes of a Pacific Northwest nation speaks volumes about their seasonal economy, their spiritual practices tied to salmon runs, and their deep understanding of their ecosystem.

The very act of identifying "Native American tribes" on a map is also a complex issue of identity. The term "tribe" itself is often a colonial imposition, failing to capture the political sophistication and distinct nationhood of many Indigenous groups. Modern atlases increasingly use the terms "nations" or "peoples," reflecting a more accurate understanding of self-determination and sovereignty. These maps also highlight the sheer diversity of Indigenous identities, countering monolithic stereotypes and revealing the unique histories of hundreds of distinct peoples.

Maps as Tools of Resistance and Reclamation

In the modern era, historical atlas maps have become crucial tools for Native American nations in their ongoing struggles for sovereignty, land rights, and cultural preservation. They are used in legal battles to assert treaty rights, challenge historical injustices, and demonstrate continuous occupancy of traditional territories. Maps highlighting specific treaty boundaries, for instance, are vital evidence in land claims cases, demonstrating where promises were made and subsequently broken.

Indigenous communities are also actively engaged in their own mapping initiatives, often utilizing advanced GIS (Geographic Information Systems) technology. These "counter-maps" or "decolonizing maps" serve to reclaim narrative control. They prioritize Indigenous perspectives, depicting sacred sites, ancestral migration routes, traditional resource management areas, and areas of cultural significance that might be overlooked or misrepresented on conventional maps. These maps are not just about geography; they are about self-determination, empowering communities to define their own territories, histories, and futures. They are a visual manifestation of cultural resurgence, allowing communities to tell their stories on their own terms.

Engaging with Atlas Maps: A Traveler’s and Learner’s Guide

For the traveler and history enthusiast, engaging with Native American historical atlas maps offers an unparalleled opportunity for deeper understanding and responsible engagement.

- Read Critically: Understand that every map has a bias, a perspective, and a purpose. Ask: Who made this map? When was it made? What information is included or excluded? What narrative does it promote?

- Look for Layers: Seek out atlases that provide multiple layers of information: pre-contact territories, successive treaty cessions, reservation boundaries, and contemporary Indigenous land claims. This layering reveals the dynamic historical process of land loss and the ongoing struggle for recognition.

- Connect to Place: When visiting a region, consult these maps to understand which Indigenous nations traditionally inhabited that land. Learn their names, their history, and their contemporary presence. Many maps include information about federally recognized tribes and their current reservation lands.

- Seek Indigenous Voices: Supplement map-reading with primary sources, oral histories, and contemporary accounts from Indigenous scholars and community members. Visit tribal museums, cultural centers, and historical sites that are curated and interpreted by Native peoples themselves.

- Respect and Acknowledge: Understanding the historical context provided by these maps fosters a deeper respect for the land and its original inhabitants. Acknowledge the traditional territories you are visiting, support Indigenous-owned businesses, and be mindful of local customs and protocols.

- Challenge Misconceptions: Use your knowledge from these maps to challenge common historical inaccuracies, such as the notion that Native Americans "vanished" or that their history ended with European contact. These maps clearly demonstrate a continuous presence and an ongoing, vibrant cultural life.

In conclusion, Native American historical atlas maps are essential instruments for comprehending the profound and often painful history of North America. They visually articulate the complex relationship between land, identity, and sovereignty, from ancient migrations to contemporary struggles for self-determination. For the curious traveler and dedicated student of history, these maps are not merely guides to physical locations but portals to a richer, more nuanced understanding of Indigenous nations – their resilience, their enduring cultures, and their vital, ongoing presence in the story of the continent. They invite us to see the land not just as geography, but as a living testament to history, identity, and the unbroken spirit of its first peoples.