Here is a 1200-word article explaining the Native American cultural regions map, focusing on history and identity, suitable for a travel and history education blog.

>

Beyond Borders: Unveiling the Living Tapestry of Native American Cultural Regions

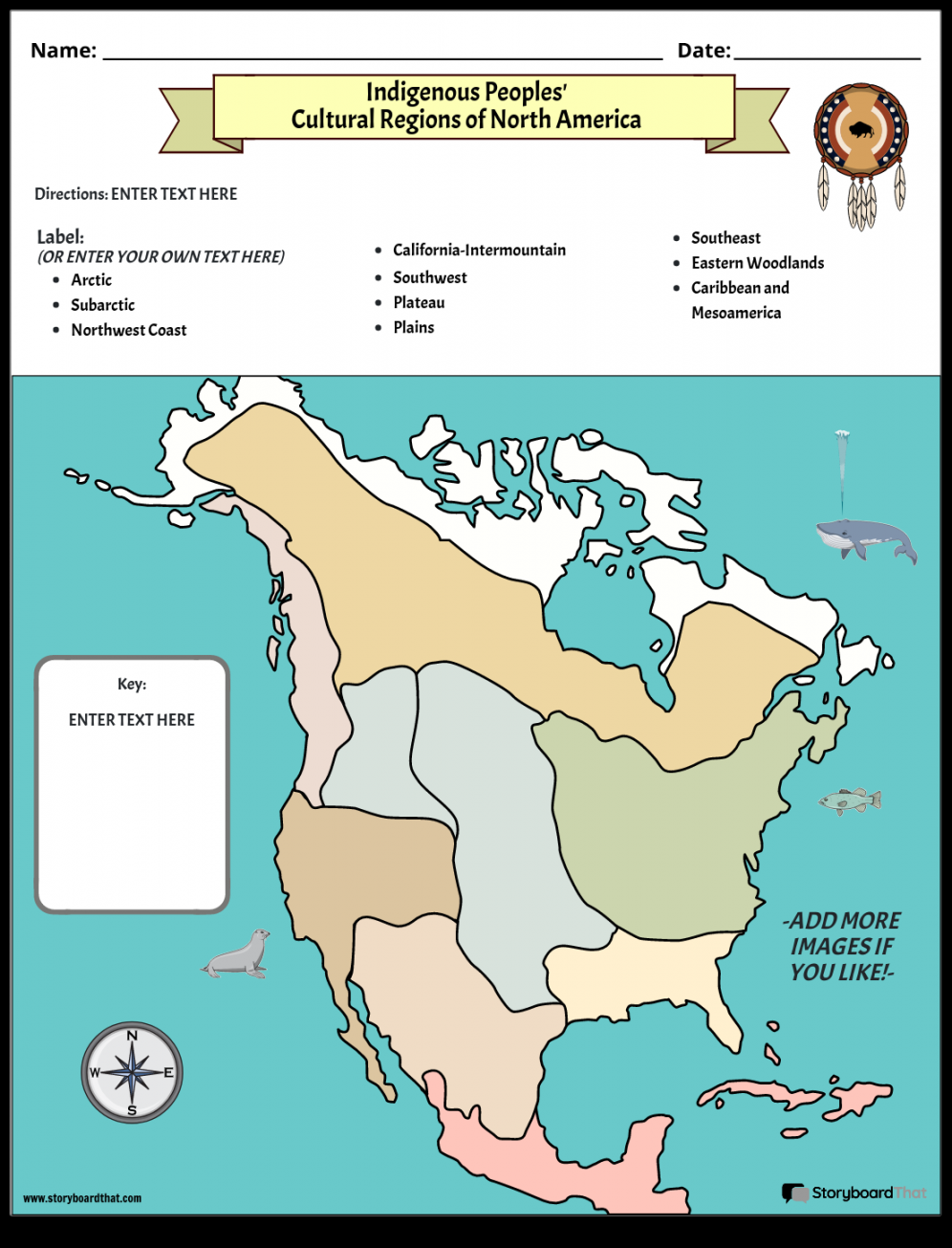

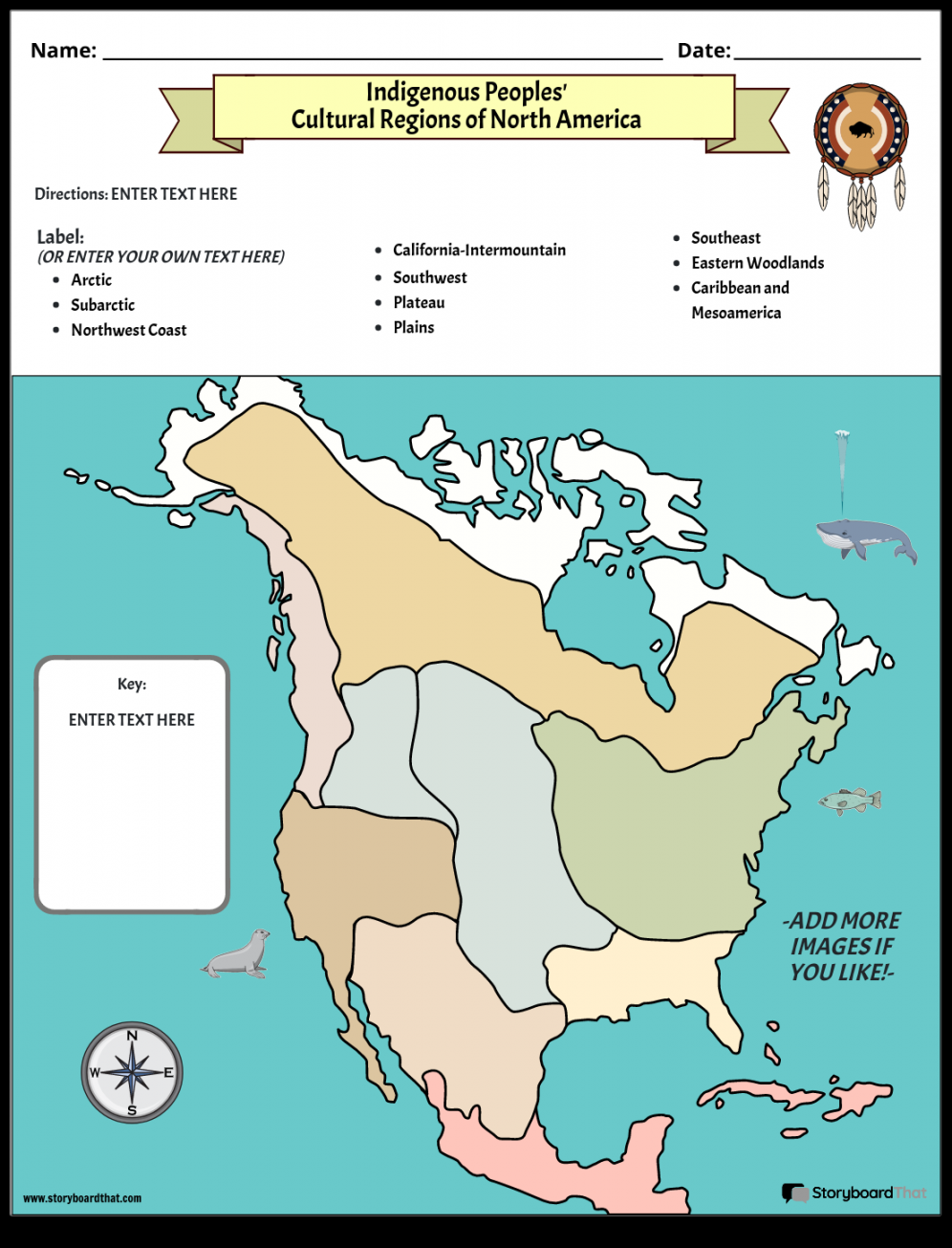

The map of Native American cultural regions is far more than a cartographic exercise; it is a profound visual narrative of resilience, innovation, and enduring identity. For travelers and history enthusiasts alike, understanding this map is crucial for moving beyond monolithic stereotypes and appreciating the extraordinary diversity of Indigenous peoples across North America. This isn’t just about tracing lines on paper; it’s about uncovering millennia of history, unique ways of life, and the vibrant, ongoing presence of hundreds of distinct nations.

The Challenge of Mapping Indigenous America: A Dynamic History

Before delving into specific regions, it’s vital to acknowledge the inherent complexities in mapping Indigenous territories. Pre-contact, boundaries were often fluid, defined by kinship, trade networks, and shared resource areas rather than rigid European-style borders. These territories were dynamic, shifting with environmental changes, alliances, and conflicts. European cartography, however, often imposed static lines, flattening the rich, nuanced understanding Indigenous peoples had of their own lands.

Furthermore, many historical maps reflect a colonial perspective, either erasing Indigenous presence or misrepresenting it. Modern cultural region maps attempt to categorize groups based on shared environmental adaptations, linguistic similarities, and cultural practices (like housing, food sources, and social structures) that developed over thousands of years in specific geographical contexts. These regions are not always perfectly distinct, and there’s often overlap, reflecting the complex interactions between neighboring peoples. The key takeaway is that these maps represent a snapshot, a best effort to illustrate the incredible diversity that existed and continues to thrive.

Exploring the Cultural Regions: A Journey Through Identity and Adaptation

Let’s embark on a journey through these remarkable cultural regions, each telling a distinct story of human ingenuity, spiritual connection to the land, and an enduring sense of identity.

1. The Arctic and Subarctic: Masters of the Frozen Frontier

- Geography: Spanning the northernmost reaches of North America, from Alaska across Canada to Greenland. Characterized by tundra, taiga, permafrost, and extreme cold.

- Identity & Adaptation: Life here demanded unparalleled resourcefulness. Peoples like the Inuit, Yup’ik, Gwich’in, and Dene developed specialized hunting techniques for marine mammals (seals, whales) and caribou. Their knowledge of snow and ice was foundational, leading to the creation of ingenious tools, warm clothing from animal hides and furs, and temporary dwellings like igloos. Their spiritual traditions often centered on respect for the animals that sustained them and the vast, powerful landscape. Community cooperation was paramount for survival.

- Historical Note: These regions were among the last to experience significant European contact, preserving many traditional ways longer than others. However, the fur trade and later resource extraction had profound impacts.

2. The Northwest Coast: Abundance from the Sea and Forest

- Geography: A narrow strip of land along the Pacific coast, from southern Alaska down to northern California, blessed with temperate rainforests, abundant salmon rivers, and a rich ocean.

- Identity & Adaptation: The sheer abundance of resources (salmon, cedar, shellfish) allowed for settled, hierarchical societies with complex social structures, elaborate art forms, and rich ceremonial life. Tribes like the Haida, Tlingit, Kwakwaka’wakw (Kwakiutl), and Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka) are renowned for their magnificent totem poles, cedar plank longhouses, intricate weaving, and the potlatch ceremony – a display of wealth and generosity that reinforced social status. Their identity was deeply tied to their lineage, their artistic expression, and their stewardship of the abundant natural world.

- Historical Note: Early contact brought devastating diseases and conflicts over resources, but the resilience of these cultures is evident in the ongoing revival of languages, art, and traditional governance.

3. The Plateau: Riverine Lifeways and Seasonal Cycles

- Geography: Located between the Cascade Mountains and the Rocky Mountains, encompassing parts of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and British Columbia. Defined by major river systems (like the Columbia and Fraser) and a varied landscape of forests, grasslands, and arid lands.

- Identity & Adaptation: Peoples such as the Nez Perce, Yakama, Spokane, and Kootenai developed a lifeway centered on the seasonal cycles of salmon runs, root gathering (like camas), and hunting. They often lived in semi-subterranean pit houses in winter and portable mat lodges (tule mat lodges) in summer. Their culture fostered strong community bonds, sophisticated fishing technologies, and an intimate understanding of their diverse ecosystem.

- Historical Note: The Plateau peoples played a crucial role in the early horse trade, which transformed their mobility and hunting capabilities, leading to increased interaction with Plains tribes. Later, they faced intense pressure over their traditional fishing grounds.

4. The Great Basin: Adapting to Aridity

- Geography: A vast, arid region between the Sierra Nevada and Rocky Mountains, covering Nevada, Utah, and parts of surrounding states. Characterized by deserts, scrublands, and scattered mountain ranges.

- Identity & Adaptation: Tribes like the Shoshone, Paiute, and Ute developed highly adaptive, mobile lifestyles in an environment of scarce resources. They lived in small, extended family groups, foraging for seeds, nuts, roots, and small game. Their housing included temporary brush shelters or wikiups. Their culture emphasized self-sufficiency, deep ecological knowledge, and a strong sense of community essential for survival in harsh conditions.

- Historical Note: This region was heavily impacted by the California Gold Rush and subsequent settler expansion, which severely disrupted traditional lifeways and led to significant land loss.

5. California: A Mosaic of Cultures

- Geography: The diverse ecological zones of present-day California, from redwood forests to deserts, mountains to coastlines.

- Identity & Adaptation: This region boasted the highest pre-contact population density and the greatest linguistic diversity in North America, with over 100 distinct groups. Tribes like the Pomo, Miwok, Chumash, and Yurok adapted to local environments, utilizing acorns as a staple food, fishing, hunting, and intricate basket weaving. Their identities were closely tied to their specific territories, languages, and unique spiritual practices. Despite environmental variation, many shared a reverence for the natural world and sophisticated resource management techniques.

- Historical Note: Spanish missions and later the Gold Rush devastated California’s Indigenous populations through disease, forced labor, and violence, yet many communities have persevered and are revitalizing their cultures today.

6. The Southwest: Farmers of the Desert

- Geography: Arid and semi-arid lands of Arizona, New Mexico, and parts of Utah, Colorado, and Texas, featuring mesas, canyons, and deserts.

- Identity & Adaptation: This region is home to two primary cultural traditions: the Pueblo peoples (like the Hopi, Zuni, Acoma), known for their multi-story adobe villages and sophisticated dryland agriculture (corn, beans, squash), and the Athabaskan-speaking peoples (Navajo/Diné, Apache), who arrived later and became adept hunters, gatherers, and eventually pastoralists. Both groups developed rich spiritual practices, intricate weaving, pottery, and ceremonial life deeply connected to their unique environment. Their identity is inseparable from their connection to ancestral lands and their distinctive architectural and artistic traditions.

- Historical Note: The Spanish colonization brought profound changes, including new agricultural techniques and livestock, but also introduced forced labor and religious conversion. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 stands as a testament to their resistance and enduring sovereignty.

7. The Great Plains: Horse, Buffalo, and Mobility

- Geography: The vast grasslands stretching from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains, from Canada to Texas.

- Identity & Adaptation: This region is often what comes to mind when people think of "Native Americans." Tribes like the Lakota (Sioux), Cheyenne, Comanche, and Blackfeet developed a highly mobile culture centered around the buffalo hunt. The introduction of the horse by Europeans revolutionized their way of life, enabling more efficient hunting, greater mobility, and enhanced warfare. They lived in portable tipis, utilized every part of the buffalo for food, clothing, and tools, and developed powerful warrior societies and elaborate spiritual ceremonies, including the Sun Dance. Their identity was forged in their relationship with the buffalo and the vast open land.

- Historical Note: The Plains Wars of the 19th century, driven by westward expansion and the decimation of the buffalo herds, represent a tragic chapter of conflict and forced displacement, yet the spirit and traditions of these nations remain strong.

8. The Northeast Woodlands: Forest Dwellers and Confederacies

- Geography: The dense forests and fertile river valleys of eastern North America, from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic coast.

- Identity & Adaptation: Peoples like the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy), Wampanoag, Lenape, and Algonquin developed a mixed economy of agriculture (the "Three Sisters": corn, beans, squash), hunting, fishing, and gathering. They lived in longhouses (Haudenosaunee) or wigwams, and developed sophisticated political systems, including the groundbreaking Great Law of Peace of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, which influenced early American democracy. Their identity was rooted in their connection to the forest, their agricultural practices, and their strong kinship and political alliances.

- Historical Note: This region was among the first to experience sustained European contact, leading to complex alliances, devastating wars, and immense land loss. However, many nations have maintained their sovereignty and cultural practices.

9. The Southeast Woodlands: Mound Builders and Complex Societies

- Geography: The warm, fertile lands of the southeastern United States, characterized by rich soils, extensive river systems, and coastal plains.

- Identity & Adaptation: Tribes such as the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole developed highly organized agricultural societies, cultivating corn, beans, squash, and tobacco. They built impressive earthen mounds for ceremonial and residential purposes (e.g., Cahokia, Etowah Mounds), lived in wattle-and-daub houses, and developed complex social hierarchies and extensive trade networks. Their identity was shaped by their agricultural prowess, their ceremonial centers, and their vibrant community life.

- Historical Note: European diseases and the brutal policy of Indian Removal (Trail of Tears) in the 19th century devastated these nations, forcing many from their ancestral lands. Despite this, their cultures and governments continue to thrive today.

Beyond the Borders: Shared Values, Distinct Voices

While each region fostered unique cultural expressions, common threads weave through Indigenous philosophies: a deep spiritual connection to the land and all living things, an emphasis on community and reciprocal relationships, the importance of oral traditions for transmitting knowledge, and a holistic worldview that integrates spiritual, social, and environmental well-being.

The Map Today: A Legacy of Sovereignty and Self-Determination

Today, the Native American cultural regions map isn’t merely a historical artifact. It serves as a powerful reminder of the pre-colonial landscape and informs contemporary efforts toward land back, cultural revitalization, and self-determination. Modern tribal nations, though often on reduced land bases (reservations), continue to assert their sovereignty, govern their communities, and revitalize their languages, ceremonies, and artistic traditions. The map underscores that Indigenous peoples are not a relic of the past but vibrant, evolving societies.

For the Traveler and Learner: Engaging with Indigenous History Respectfully

For those inspired to learn more, approaching Indigenous history and culture with respect and an open mind is paramount:

- Acknowledge Land: Begin by learning whose ancestral lands you are on. Many organizations and apps can help.

- Research & Respect: When visiting Indigenous cultural sites or events, research protocols, ask permission where necessary, and always respect local customs.

- Support Indigenous Businesses: Seek out and support Native-owned businesses, artists, and cultural centers.

- Listen to Indigenous Voices: Prioritize learning directly from Indigenous scholars, writers, artists, and community members.

- Challenge Stereotypes: Actively dismantle romanticized or inaccurate portrayals of Native Americans.

Conclusion: A Living Tapestry

The Native American cultural regions map is a dynamic, living testament to the enduring presence, profound diversity, and incredible resilience of Indigenous peoples. It invites us to look beyond simplistic narratives and embrace the complexity, richness, and beauty of North America’s first nations. By understanding these regions, we gain not just historical knowledge, but a deeper appreciation for the intricate relationship between humanity and the environment, and the ongoing journey of identity and self-determination for millions of Indigenous people today. Their stories are woven into the very fabric of this continent, waiting to be heard and respected.