The Unseen Lines: Decoding the Native Tribe Maps of the Trail of Tears

The story of the Trail of Tears is etched not just in history books, but profoundly on the very landscape of the United States. While many envision a single, tragic path, the reality is far more complex, represented by intricate maps that tell a devastating tale of forced removal, shattered sovereignty, and enduring resilience. These maps are more than mere geographical markers; they are living documents that chronicle the identity, ancestral homelands, and the catastrophic journey of numerous Native American nations. For the discerning traveler and history enthusiast, understanding these maps offers a profound, respectful entry point into one of America’s darkest chapters and the powerful spirit of its Indigenous peoples.

I. The Pre-Removal Landscape: A Tapestry of Nations and Identity

Before the lines of forced removal were drawn, the southeastern United States was a vibrant mosaic of sovereign Indigenous nations, each with distinct cultures, languages, governance, and deep spiritual ties to their ancestral lands. The maps of this era depict not an empty wilderness, but a sophisticated network of towns, agricultural fields, hunting grounds, and trade routes. At the heart of the Trail of Tears narrative are the "Five Civilized Tribes" – the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole – a designation bestowed upon them by European settlers due to their adoption of certain aspects of settler culture, including written languages, constitutional governments, and farming techniques.

The Cherokee Nation, primarily located across parts of Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Alabama, possessed a highly organized society. Their map would show extensive farmlands, well-established towns like New Echota (their capital), and a government modeled on the U.S. Constitution, complete with a bicameral legislature and a judicial system. Their identity was intrinsically linked to the mountains and valleys of their homeland, a place rich with sacred sites and ancestral burial grounds.

The Choctaw Nation occupied a vast territory in what is now Mississippi and Alabama. Their maps would highlight fertile river valleys, significant trade networks, and a long history of alliances and conflicts with neighboring tribes and European powers. The Choctaw were among the first to face forced removal, their identity tied to the deep south, its rich soil, and their traditional Miko (chief) system.

The Chickasaw Nation, neighbors to the Choctaw, held lands primarily in northern Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee. Renowned as fierce warriors and skilled traders, their maps would show strategic locations and strong defensive positions. Their identity was defined by their independence and their strong sense of community, deeply rooted in their specific territories.

The Creek (Muscogee) Nation was a powerful confederacy spanning much of Alabama and Georgia, composed of various towns and clans united by language and culture. Their maps would illustrate a complex political structure of "red" (war) and "white" (peace) towns, along with extensive farming lands along major rivers. Their collective identity was forged through intricate social structures and a shared heritage.

The Seminole Nation, a dynamic confederacy primarily in Florida, evolved from various Creek groups who migrated south, along with African Americans escaping slavery. Their maps would emphasize the unique environment of the Everglades and Florida’s coastal regions, crucial for their unique blend of agriculture, hunting, and fishing. Their identity was marked by fierce independence and a history of successful resistance against both Spanish and American encroachment.

These pre-removal maps fundamentally represent sovereignty – the right of self-governance within defined territories. The lines drawn on these maps were not arbitrary; they were the boundaries of nations, deeply embedded with cultural significance, ancestral memory, and the very identity of the people who called them home.

II. The Genesis of Displacement: Lines of Conflict and Betrayal

The seemingly stable lines of Indigenous sovereignty began to fracture under immense pressure from the expanding United States. Driven by the insatiable demand for land for cotton cultivation, the discovery of gold on Cherokee lands in Georgia, and the ideology of Manifest Destiny, a political movement for "Indian Removal" gained momentum.

The pivotal moment arrived with the Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by President Andrew Jackson. This act authorized the President to negotiate treaties for the removal of Native American tribes from their ancestral lands in the Southeast to territories west of the Mississippi River, specifically designated as "Indian Territory" (present-day Oklahoma). While framed as "voluntary exchange," the reality was often coercion, military threat, and outright fraud.

Maps of this period show the shrinking boundaries of Native lands, surrounded by ever-encroaching settler states. They illustrate the legal battles, such as the Cherokee Nation’s victory in Worcester v. Georgia (1832), where the Supreme Court affirmed Cherokee sovereignty and stated Georgia law had no force on Cherokee land. However, President Jackson famously defied the ruling, declaring, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it." This defiance effectively rendered the legal maps of sovereignty meaningless in the face of political will and military power.

The most controversial "treaty" associated with the Cherokee removal was the Treaty of New Echota (1835). Signed by a minority faction of the Cherokee Nation, the Treaty Party, without the consent of the majority of the tribe or its Principal Chief, John Ross, it ceded all Cherokee lands east of the Mississippi in exchange for land in Indian Territory and financial compensation. The vast majority of the Cherokee Nation did not recognize its legitimacy, but the U.S. government used it as justification for the impending removal. Maps highlighting the lands ceded by this illegitimate treaty show the dramatic shift from sovereign nation to contested territory, setting the stage for the tragic forced marches.

III. The Trail Itself: Routes of Suffering and Resilience

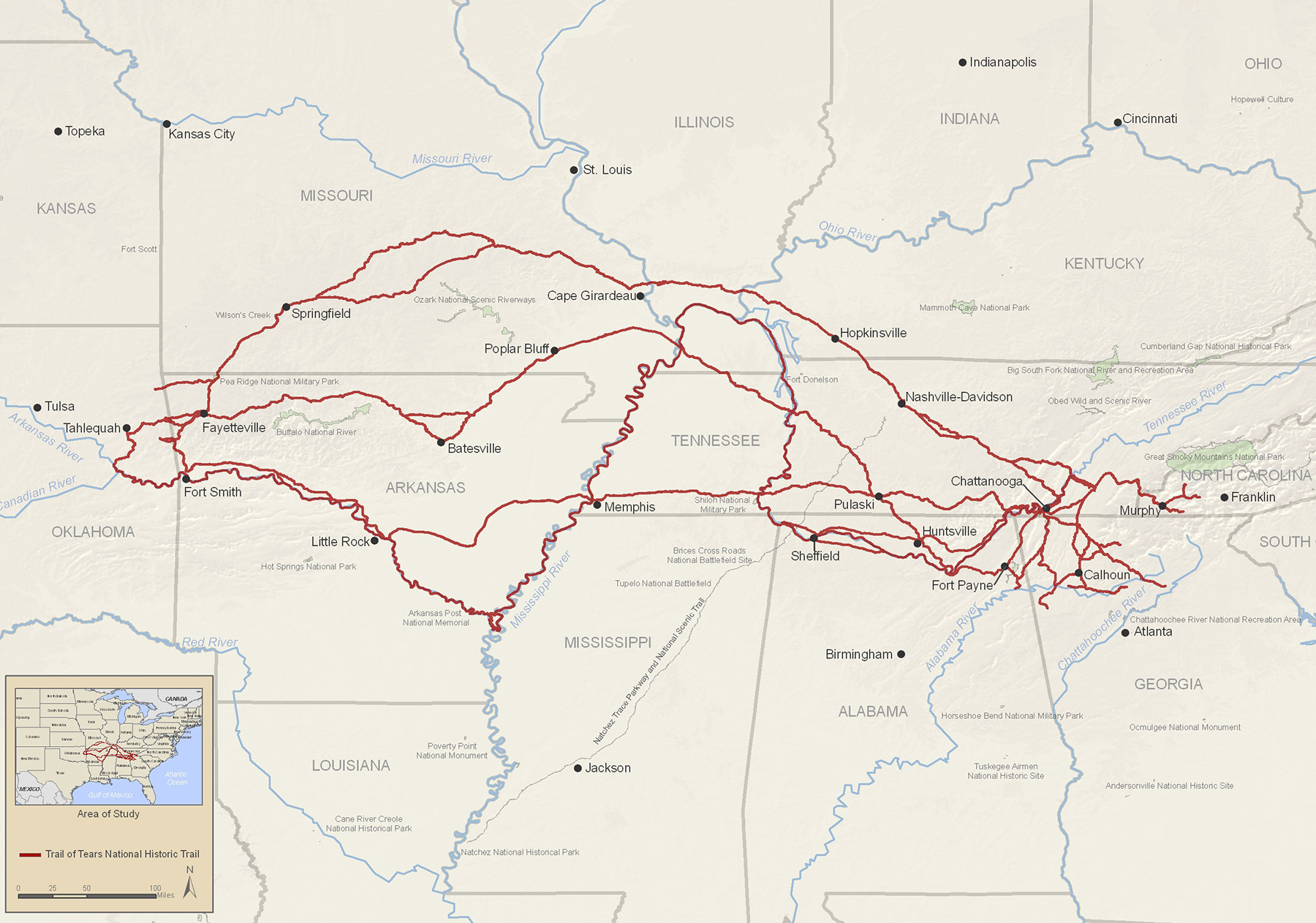

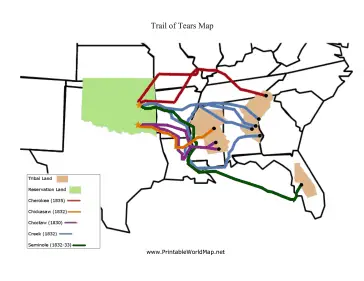

The maps detailing the actual Trail of Tears are perhaps the most harrowing. They depict multiple, often overlapping, routes taken by the various tribes, each line representing unimaginable suffering, loss, and the forced severance from ancestral lands. These were not singular, well-paved roads, but arduous journeys by foot, wagon, and boat, spanning hundreds of miles through unforgiving terrain and weather.

The Choctaw were the first of the Five Civilized Tribes to be forcibly removed, beginning in 1831. Their maps show routes primarily through Mississippi and Arkansas, often in the brutal winter months, leading to widespread disease and death. Their journey coined the term "Trail of Tears" even before the Cherokee removal.

The Creek followed, with forced removals occurring between 1834 and 1837, often in chains, driven by military forces. Their routes on the map stretch from Alabama across Mississippi and Arkansas, a testament to a people forcibly uprooted from their traditional homes.

The Chickasaw, after witnessing the fate of their neighbors, negotiated a treaty for removal in 1837, allowing them to manage their own relocation, albeit at their own expense. Their maps show a more organized, though still difficult, migration from Mississippi and Alabama, purchasing lands from the Choctaw in Indian Territory.

The Cherokee removal, the largest and most widely documented, occurred primarily in the fall and winter of 1838-1839. Approximately 16,000 Cherokee men, women, and children were rounded up by U.S. soldiers and state militias and forced into stockades before being marched westward. The maps of the Cherokee Trail of Tears show numerous routes, both overland and riverine. The land routes cut across Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas, while water routes utilized the Tennessee, Ohio, Mississippi, and Arkansas Rivers. It’s estimated that over 4,000 Cherokee died during this forced migration from disease, starvation, and exposure. Each line on these maps signifies a path of death, a testament to a deliberate act of ethnic cleansing.

The Seminole removal proved the most protracted and costly. Their fierce resistance in the Florida Everglades led to three Seminole Wars (1816-1858), the longest and most expensive Indian wars in U.S. history. Maps of Seminole removal routes are complex, showing both forced migrations to Indian Territory and the areas of ongoing conflict and hideouts within Florida. Many Seminoles were never fully removed, and their descendants remain in Florida today.

These maps, with their multiple, converging lines, starkly illustrate the scale of the forced displacement. They are a geographic representation of a humanitarian crisis, where the suffering of thousands is traced across the landscape of a nascent nation.

IV. Arrival in Indian Territory: Rebuilding and Redefining Identity

The endpoint of these tragic journeys was Indian Territory, a vast expanse of land in what is now Oklahoma. Maps of this destination show the newly designated tribal lands for each of the removed nations. Here, the challenge was not merely survival, but the arduous task of rebuilding their societies, governments, and economies from scratch, often on unfamiliar land and amidst existing Indigenous communities.

Despite the profound trauma, the relocated tribes demonstrated extraordinary resilience. They re-established their constitutional governments, built new schools and churches, developed new agricultural practices suited to the land, and revitalized their cultural traditions. The Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole nations in Oklahoma today are direct descendants of those who survived the Trail of Tears, their identity forged in the crucible of removal but strengthened by their ability to adapt and endure.

Maps of modern Oklahoma still reflect this history, showing the distinct tribal jurisdictions and lands. These lines represent not only a historical legacy but also the ongoing struggle for self-determination and the vibrant continuation of Native American identity.

V. The Enduring Legacy: Identity, Memory, and Modern Engagement

The maps of the Trail of Tears are not static historical artifacts; they are living documents that continue to inform contemporary Native American identity, land claims, and cultural preservation efforts. The shared experience of removal created a collective memory that binds these nations, fostering both a deep understanding of historical injustice and an unyielding commitment to their heritage.

Today, maps related to the Trail of Tears serve several crucial purposes:

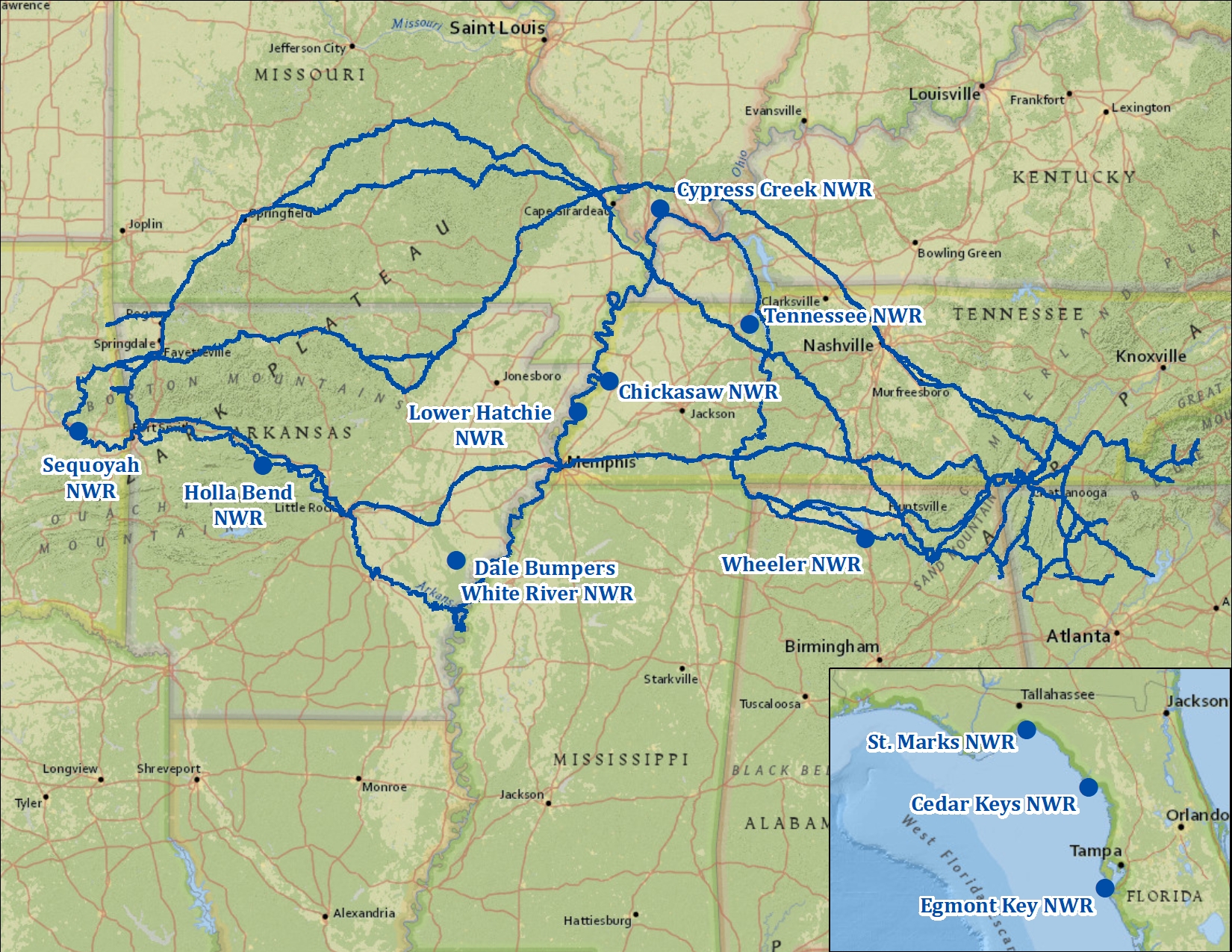

- National Historic Trail: The Trail of Tears National Historic Trail highlights the primary routes of removal, allowing visitors to walk in the footsteps of their ancestors, learn about the specific challenges faced, and reflect on the history. Maps of this trail connect specific sites – historic homesteads, military encampments, river crossings, and cemeteries – providing tangible links to the past.

- Education and Awareness: These maps are vital educational tools, helping to visualize the scale of the removal and the specific geographies of each tribe’s journey. They challenge simplistic narratives and provide a nuanced understanding of the profound impact on Indigenous communities.

- Sovereignty and Identity: For the tribal nations, these maps reinforce their historical connection to their ancestral lands and their modern existence as sovereign nations. They are a powerful symbol of survival and the continuous assertion of their identity despite attempts at erasure.

For the traveler seeking a deeper understanding, engaging with these maps offers a pathway to meaningful historical education. Visiting sites along the National Historic Trail, exploring tribal museums and cultural centers in both the ancestral homelands and Oklahoma, and supporting Indigenous-led initiatives provide invaluable opportunities. It’s crucial to approach these experiences with respect, humility, and a willingness to listen to the voices and perspectives of the Native American communities themselves.

In conclusion, the maps of the Trail of Tears are far more than just lines on paper. They are powerful narratives of land, identity, injustice, and an extraordinary saga of human resilience. They compel us to remember, to learn, and to honor the enduring spirit of the Native American nations who, despite profound loss, continue to thrive, their stories forever woven into the fabric of this land. Understanding these maps is not just a historical exercise; it is an act of acknowledging a foundational truth about American history and the vibrant, continuing presence of its Indigenous peoples.