Tracing the Unseen: An 18th-Century Native American Tribal Lands Map as a Portal to History and Identity

To gaze upon an 18th-century map purporting to delineate Native American tribal lands is to confront a document far more complex than its lines and labels suggest. It is not merely a geographical representation but a testament to profound cultural clashes, imperial ambitions, and the enduring spirit of Indigenous peoples. For the discerning traveler and history enthusiast, understanding these maps—and their inherent limitations—unlocks a deeper appreciation for the landscapes we traverse and the rich, often tragic, narratives embedded within them. This article will explore the historical context, the European gaze versus Indigenous realities, and the lasting legacy of identity tied to these contested territories, providing a framework for engaging with this pivotal era.

The European Gaze: Imposing Order on an Unfamiliar World

The 18th century was a period of intense European colonial expansion across North America. British, French, and Spanish powers vied for dominance, and their competition profoundly shaped the continent’s political and demographic landscape. Maps from this era were primarily instruments of power: tools for claiming territory, planning military campaigns, charting resources, and facilitating trade. They reflected a distinctly European worldview, one that often failed to grasp, or intentionally disregarded, Indigenous concepts of land.

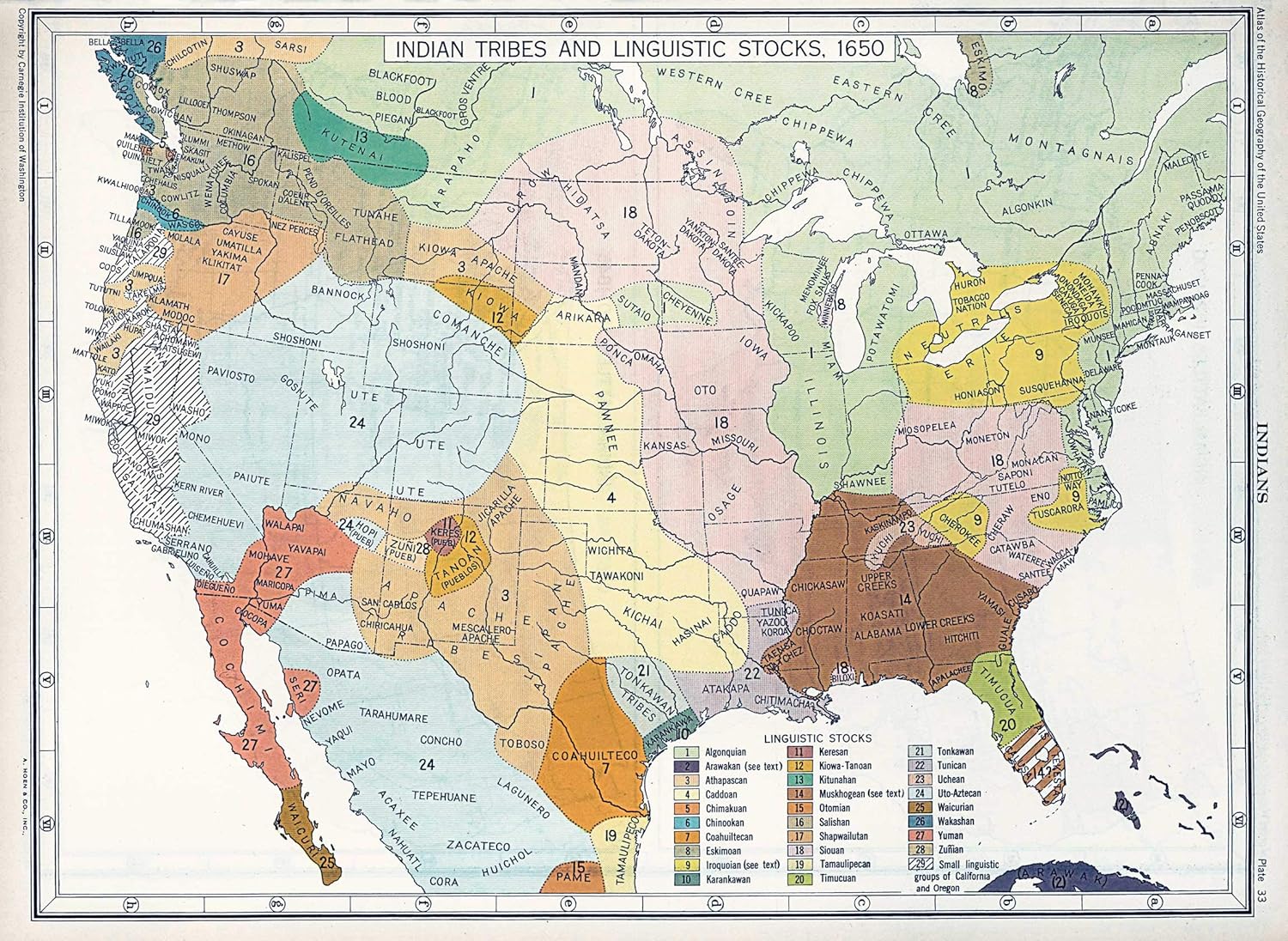

European cartographers, operating under the doctrines of terra nullius (empty land) or the belief in their own superior civilization, sought to impose fixed, geometric boundaries onto lands that Indigenous nations understood in far more fluid, ecological, and spiritual terms. These maps would often show vast tracts labeled "unclaimed" or simply "Indian Territory" without recognizing the complex systems of governance, resource management, and inter-tribal relations that defined these regions. Where tribal names did appear, they were frequently anglicized, francized, or Hispanized, sometimes mislocated, and rarely conveyed the intricate relationships between distinct but often allied or related groups.

For example, a map might depict the "Cherokee Nation" as a single, monolithic entity, overlooking the intricate network of autonomous towns and councils that constituted Cherokee governance. Similarly, the sprawling territories of the "Sioux" (a French corruption of "Nadouessioux," an Ojibwe exonym meaning "little snakes") would be marked without differentiating between the Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota divisions, each with their own bands, territories, and dialects. This reductionist approach stripped Indigenous nations of their nuanced identities and sovereign complexities, simplifying them into obstacles or assets in the colonial project.

Indigenous Realities: Land as Identity, Relationship, and Sustenance

In stark contrast to the European understanding, Indigenous peoples across North America did not view land as a commodity to be bought, sold, or "owned" in perpetuity by individuals or states. Their relationship with the land was holistic, encompassing spiritual connection, ancestral memory, and ecological stewardship. Territories were defined not by arbitrary lines on paper but by natural landmarks—rivers, mountains, forests—and by the patterns of seasonal migration, hunting grounds, fishing rights, and agricultural plots.

Identity was intrinsically tied to place. A person was not merely a member of a tribe but a child of a specific landscape, shaped by its resources, its climate, and the spirits that resided within it. Oral traditions, origin stories, and ceremonial practices were deeply rooted in specific geographical features. To lose land was not just an economic setback; it was a severing of cultural memory, a disruption of spiritual balance, and an existential threat to identity itself.

The 18th-century map, therefore, rarely captured the dynamic nature of Indigenous land use. A "hunting ground" for one nation might overlap with the "seasonal gathering territory" of another, governed by complex agreements, alliances, and historical precedents rather than rigid borders. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, for instance, held sway over vast tracts of what is now New York and Pennsylvania, extending their influence through trade and warfare. Their control was not a matter of fixed lines but of strategic outposts, diplomatic networks, and the ability to project power. The map’s lines failed to convey the living, breathing, reciprocal relationship between people and their environment.

A Century of Conflict and Transformation: Key Regions and Their Peoples

The 18th century was a crucible for Native American nations, marked by shifting alliances, devastating wars, and the relentless pressure of colonial expansion. Examining the major regions helps illuminate the diverse experiences.

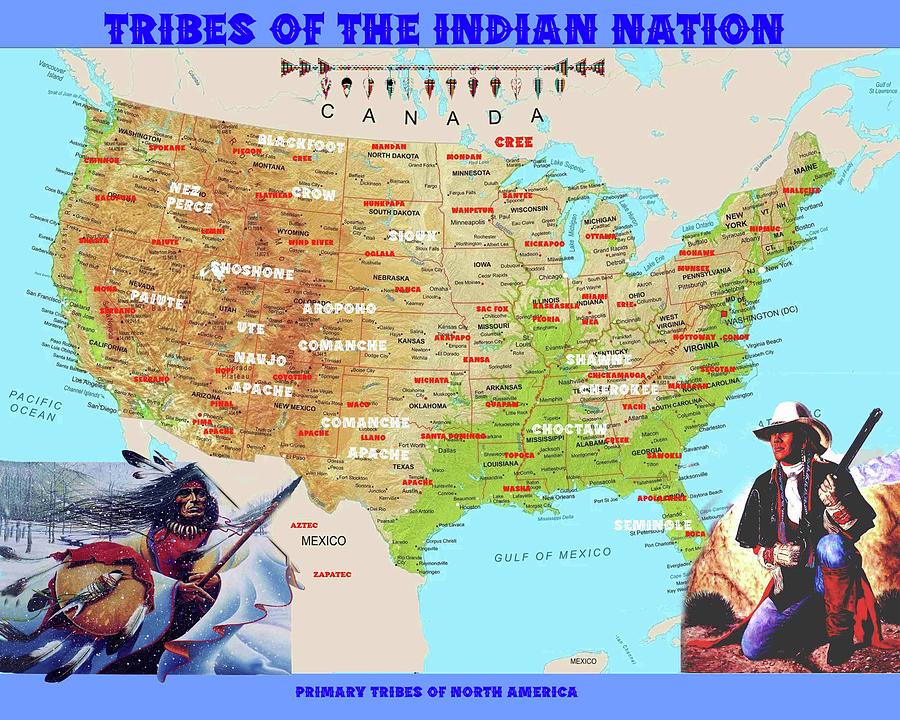

The Northeast and Great Lakes: This region was a primary battleground for French and British imperial ambitions. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora) were a formidable power, skillfully playing European empires against each other to maintain their sovereignty. Their territories were crucial for controlling trade routes and access to the interior. Nations like the Delaware (Lenape) and Shawnee, though dispossessed of their ancestral lands along the Atlantic coast, established new communities in the Ohio Valley, forming alliances and resisting further encroachment. The French and Indian War (Seven Years’ War) and the subsequent American Revolution forced these nations to make difficult choices, often with catastrophic consequences for their land base and political autonomy.

The Southeast: Dominated by the "Five Civilized Tribes"—the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole—this region saw intense pressure from burgeoning American settlements, particularly with the rise of cotton cultivation and the demand for slave labor. These nations developed sophisticated written constitutions, adopted elements of American farming, and even owned African slaves, often in attempts to safeguard their lands and sovereignty. Yet, the land hunger of the United States proved insatiable. Spanish presence in Florida offered a refuge for some, notably the Seminole, a diverse nation forged from Creek migrants, escaped slaves, and other Indigenous groups.

The Great Plains: While the major waves of American westward expansion would come later, the 18th century saw significant transformations on the Plains. The introduction of the horse by the Spanish dramatically reshaped the cultures of nations like the Lakota (Sioux), Cheyenne, and Comanche. These tribes became expert horsemen, expanding their hunting territories, particularly for buffalo, and becoming formidable military forces. Their territories, often marked vaguely on European maps, were vast and fluid, reflecting nomadic patterns and inter-tribal warfare. The early fur trade also began to draw these nations into contact with European economies, introducing new goods and, tragically, new diseases.

The Southwest: Here, the legacy of Spanish colonization was centuries old. The Pueblo peoples (e.g., Hopi, Zuni, Taos) maintained their distinct agricultural communities and spiritual traditions, often resisting Spanish attempts at cultural assimilation. The Navajo (Diné) and Apache nations, known for their raiding and adaptive strategies, occupied vast and rugged territories, often clashing with both Spanish and Pueblo settlements. European maps of this region were often even more speculative, reflecting the challenges of navigating and mapping arid, mountainous terrain and the persistent resistance of Indigenous inhabitants.

The Invisible Scars: Disease, Treaties, and Dispossession

Beyond the lines on the map, the 18th century brought forces that irrevocably altered Indigenous lifeways. European diseases—smallpox, measles, influenza—decimated populations, sometimes by 90% or more. These epidemics weakened nations, disrupted social structures, and made resistance far more difficult. The psychological and demographic impact of these plagues is an invisible but profound feature of any 18th-century "tribal lands" map.

Treaties, often depicted as formal agreements between sovereign powers, were frequently instruments of dispossession. European powers, and later the United States, used treaties to acquire land, often through coercion, misunderstanding, or outright fraud. The concept of "selling" land was often alien to Indigenous worldviews, where land was understood as belonging to all and to future generations, not a commodity to be alienated. Promises made in treaties were routinely broken, leading to further conflict and displacement. These "treaty lands" on maps represent not just territory, but broken trust and systemic injustice.

Identity and Resilience: A Living Legacy

Despite the immense pressures and losses of the 18th century, Native American identity was not extinguished. It adapted, resisted, and endured. The struggle to maintain land was fundamentally a struggle to preserve culture, language, and self-determination. The ability to navigate complex political landscapes, forge new alliances, and resist military might speaks to extraordinary resilience and sophisticated governance.

Today, when we consult an 18th-century map of Native American tribal lands, we are not looking at a static historical artifact but a portal to a living history. It challenges us to look beyond the simplistic lines and consider:

- Whose perspective is represented? Are we seeing colonial claims or Indigenous realities?

- What stories are untold? What happened to the peoples whose lands are depicted, or whose existence is erased?

- What is the legacy today? How do these historical land claims and dispossessions continue to impact contemporary Native American nations, their sovereignty, and their ongoing struggles for justice?

Engaging with the Living Map: A Call to Action for Travelers and Learners

For the history-minded traveler, engaging with these maps offers a profound opportunity to connect with the land in a more meaningful way.

- Seek Out Indigenous Voices: Do not rely solely on colonial-era maps or narratives. Visit tribal museums, cultural centers, and historical sites curated by Native American nations themselves. These institutions offer authentic perspectives, often presenting their own maps and oral histories.

- Understand Treaty Lands: Many areas we now inhabit are still, by law, unceded treaty lands. Learning about the treaties that pertain to your region provides crucial context for understanding Indigenous sovereignty today.

- Visit Ancestral Lands with Respect: When visiting national parks, historical sites, or even just hiking trails, research which Indigenous nations are the traditional custodians of that land. Acknowledge their enduring presence and history. Many parks and sites now include interpretive materials developed in partnership with local tribes.

- Support Indigenous Economies: Purchase goods and services from Native-owned businesses and artists. This directly supports the self-determination and cultural preservation efforts of contemporary Indigenous communities.

- Read Indigenous Histories: Dive into scholarship and literature by Native American authors and historians. This provides crucial counter-narratives to the often Eurocentric accounts of the past.

An 18th-century map of Native American tribal lands is more than just a piece of paper; it is a complex palimpsest of power, resistance, and identity. It reminds us that every inch of this continent has a deep, layered history, and that the stories of its first peoples are not confined to the past but continue to shape the present. By actively seeking to understand these maps through an Indigenous lens, we embark on a journey of deeper historical understanding, greater cultural empathy, and a more profound appreciation for the diverse tapestry of North America.